History of Roller Milling: The Origins

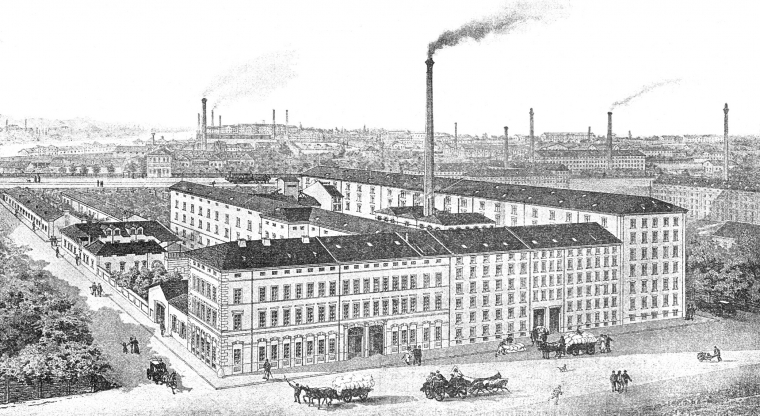

The story of the history of roller milling begins on mainland Europe, in Switzerland, during the 1830s. There, a young engineer named Jacob Sulzberger reconstructed a mill in Frauenfeld. He installed a system of three rolls placed one on top of the other and, despite having flaws, it worked. He then went on to install roller machinery in Italy, Germany and Hungary with his installations at Walzmühle, Budapest, regarded as his most successful installation.

From these early advancements on mainland Europe, we then travel to England following the footsteps of Gustav Buchholz, a Prussian engineer who went to England in 1847. He was a man who made many advancements, as regards roller machinery, but never quite made that final breakthrough, indeed one author described him as ‘on the verge of great accomplishments’ throughout his entire career (Storck and Teague, p.228). He made a machine with six pairs of rollers in a single frame. Each roller had a sieve underneath to separate the finer and coarser particles and allow the coarser elements to progress to the next roller. This was the early beginnings of what would become the ‘break’ section of the modern roller mill. His first installations were for Fison & Co., Ipswich in 1862 followed by Albert Mills, Liverpool in 1868. Albert Mills claim to have been the first complete roller plant without stones in Britain as two years later, in 1870, the stones were removed from the mill and slightly grooved rolls were installed. Despite having installed this machinery and patented his work, Buchholz’s designs never really had great success. In 1889, Seth Taylor, a prominent London miller, described Buchholz’s work as ‘so elaborate, complex, and difficult in working that it had been a failure’ (Simon, 175). Nevertheless, as he then goes on give him credit for ‘it had been the germ of the present roller milling’.

Instead, greater advances were happening back in Hungary where Abraham Ganz was pioneering the use of chilled cast-iron rolls. He had worked as a foreman in the Walzmühle foundry and started his own business in the 1840s. This business became recognised as expert in chill-casting and it maintained this reputation after Ganz’s death in 1867. He was succeeded by Andreas Mechwart who became head of Ganz & Co. and started making chilled iron rolls around 1870 which were then imported throughout the world.

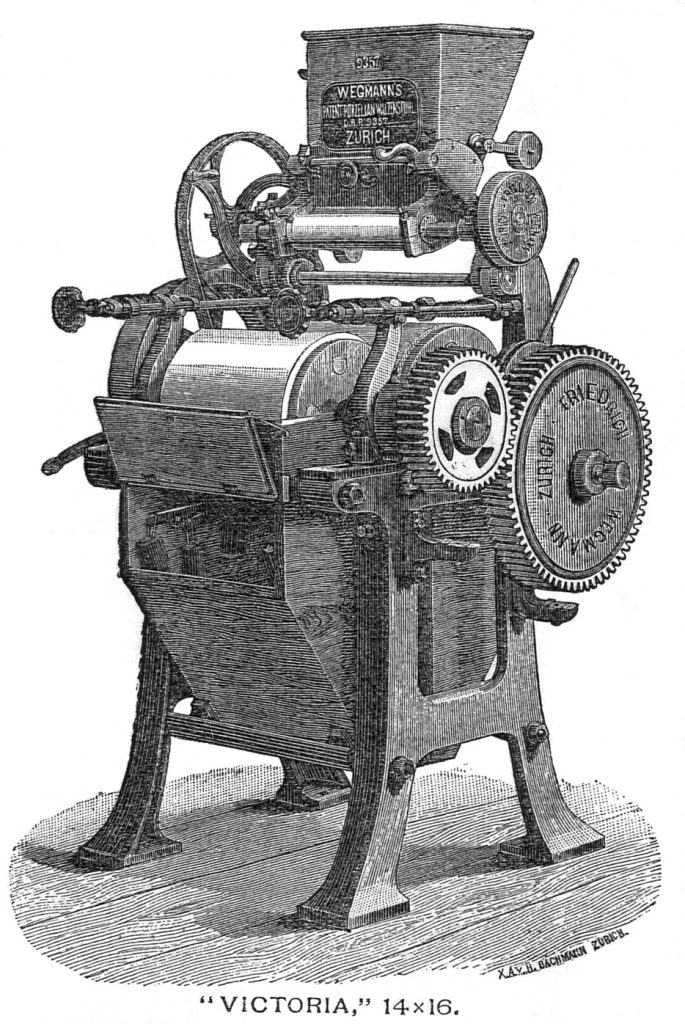

Contemporary to the developments made by Ganz & Co. in Hungary was the work done by Friedrich Wegmann of Naples who invented a porcelain roller mill for reducing semolina and middlings. By the mid-1870s these machines could be found throughout Europe with the first arrival in Britain taking place at the end of 1876. The impetus behind the trial of the machine in Britain can mainly be attributed to one man, Oscar Oexle. He had enlarged the Walzmühle workings in 1868 and then become an agent for Wegmann’s machines. During 1876 he wrote a series of articles in The Miller advocating the use of porcelain rollers and prompted a trial to take place in London in December 1876. After this trial, around 30 machines were ordered in Britain and A. B. Childs was appointed Wegmann’s agent in Britain. By 1881 Wegmann claimed to have sold 6000 machines in Europe despite his machines not being as popular in Britain where the chilled cast iron rolls were more commonly used. Nevertheless, together these two inventions had a major impact on the milling industry in Europe and was the impetus the industry needed.

Advancements in America

The story in America was slightly different and it is time to follow Oscar Oexle across the Atlantic as he visited the States in 1877, again to promote the Wegmann porcelain rollers. Up to this point, the progression of the American milling industry had been quite different to that of Europe’s. The first impetus to make the industry more modern came from Oliver Evans who developed an automatic milling system during the 1780s. These advancements were still a long way off the modern roller milling system but was nevertheless still responsible for making the industry more modern.

By the time Oscar Oexle arrived, almost 100 years after Evans’ invention, there had been more developments than just mechanising the milling system. Indeed, one author describes that ‘We may think of the decade 1870-80 as the period of ‘New Process’ milling and that of 1880-90 as the first decade of roller-milling’ (Kuhlmann, p.125). So when Oexle arrived, America was in the midst of ‘New Process’ decade, but what was ‘the principal factor in New-Process milling’ (Storck & Teague, p.213)? It was the purifier. A purifier was a machine that is ‘used to extract the finest bran particles from the endosperm (flour)’ to allow for ‘the maximum amount of flour’ to be extracted from the wheat (Walker, p.11). The story of how it arrived in America, having travelled first from France to Canada, is an interesting one and highlights key individuals in the roller flour history of America.

The history of roller milling in America is really the history of roller milling in Minneapolis as the ‘great improvement in milling in this country started in Minneapolis’ due to ‘a few broad-guage (sic) and liberal men who spent their money trying the experiments’ (Gray, Part II, p.800). Two men in particular were C. C. Washburn and C. A. Pillsbury. C. C. Washburn had a varied career and, although not a miller himself, invested heavily into the industry, was prepared to take a chance and hired knowledgeable people. In 1871 he hired George Christian to run the Washburn B Mill. Christian was then responsible for bringing the purifier machine to the Washburn mill.

Nicholas and Edmund N. La Croix were French-trained engineers who, in 1865, were induced to come to Montreal and build a mill for Alexander Faribault, a mill that would include a purifier machine. They also built one for John S. and George N. Archibald and it was their superior flour that caused Christian to try to find a way of replicating their method in the Washburn B mill. Edmund La Croix was hired and, in March 1871, La Croix completed the purifier for the mill. Gray writes that La Croix ‘did not claim to have invented the purifier, but had copied it from a French book’, yet was nevertheless seen as an innovator in the States (Gray, Part III, p.844). This invention led the way for greater efficiency and productivity, but also a bitter legal dispute.

George T. Smith worked with Christian at the Washburn B mill. Once the purifier had been installed, he invented travelling brushes that could clean the sieves automatically rather than having to have a man stand by the machine to physically clean the sieves themselves. This, and other additions to the machine, were all patented by Smith and due to ‘patent wars, deals, and consolidations’, the machines were not freely available until 1876 (Storck and Teague, p.213). Around this time Smith left the Washburn B Mill and went to work for their competition, C. A. Pillsbury and Company, where he naturally installed the purifier machine so this ‘New Process’ began to spread throughout the country. Indeed, by 1880, 2,000 of Smith’s purifiers were in use whilst by 1892, 19,000 had been sold.

However, George Christian and Washburn mills were not just responsible for introducing the purifier to America, they introduced other machines to the milling industry as well. In 1873, a group of millers from Minneapolis visited Europe to view the ‘Hungarian milling process’. This group included both C. A. Pillsbury and George Christian. On his return, he started experimenting with roller machines and in 1874, ordered 36 pairs of smooth chilled cast-iron rollers for the Washburn A mill. However, it was not until 1878 that a serious experiment with roller machinery took place after the Washburn mills suffered a great catastrophe. On 2 May 1878, there was an explosion at Washburn A mill which killed 18 people and destroyed the entire premises. Not to be deterred, Washburn paced off land for a new mill to be built, the Washburn C mill, also known as the Washburn Experimental Mill. This mill was larger than the one which had been destroyed and a portion of it was set aside. In this area, W. D. Gray installed a 150-barrel-per-day roller system as the introduction of roller machinery properly started in the Sates. The explosion also highlighted the danger of flour dust as it was this highly flammable substance that caused the explosion. Future mills then ensured that dust collectors were installed in their mills.

Back in Britain…

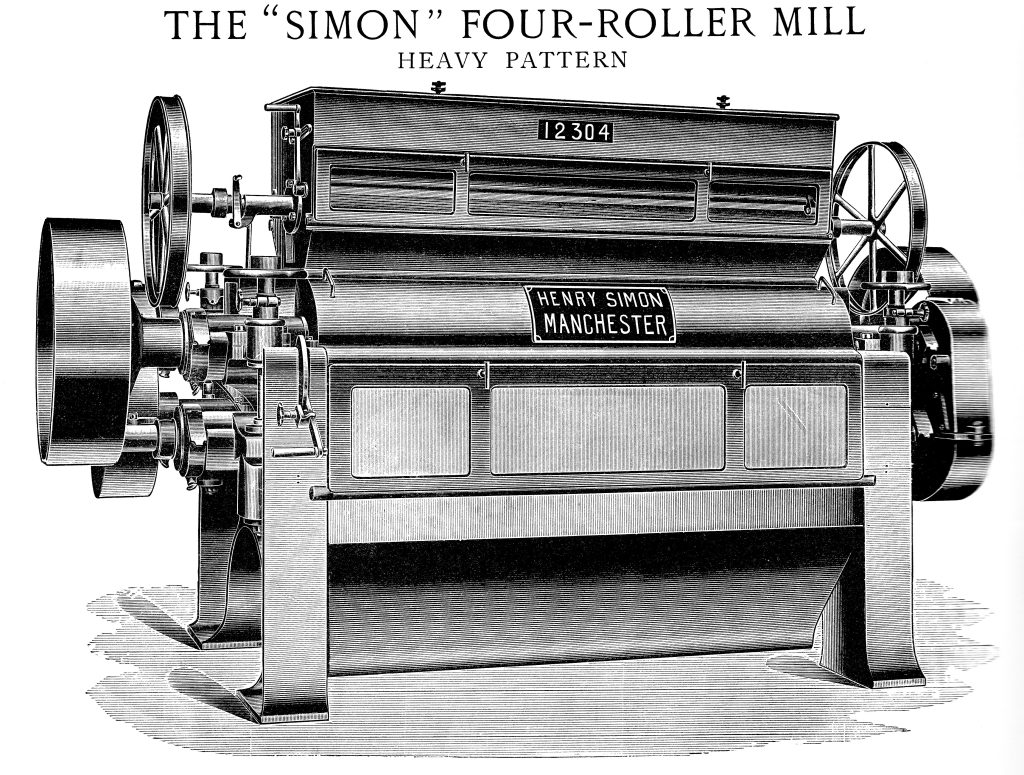

Meanwhile, 1878 was an important year for the development of roller milling in Britain as well. During this year, the first all-roller gradual-reduction mill in Britain was installed for the McDougall Brothers in Manchester by Henry Simon. The previous year, Henry Simon had joined forces with Gustav Daverio and started selling his three-high roller machine. He used this in the installation at the McDougall Brothers mill. Three years later, Simon is credited as having installed a completely automatic roller flour mill for the same firm. Some claim this was the first completely automatic roller flour mill in the world, but others report J. Harrison Carter as having been the first when he installed an automatic roller mill for John Mooney in Dublin in 1880. Nevertheless, the 1880s saw the growth of roller milling in Britain as the newly founded National Association of British and Irish Millers (NABIM) encouraged the adoption of the machines on display at exhibitions, such as the one in Islington, London in 1881, by companies, such as Henry Simon Ltd.; J. Harrison Carter; E. R. & F. Turner and W. R. Dell and Son. Roller milling in Britain was becoming an established system.

Spread of Roller Machinery in America

As seen in the Washburn mill, the 1880s saw the beginning of the use of roller machinery in America as well. After fitting the Washburn C mill with roller machinery, Gray started to convince Mr. C. A. Pillsbury to install roller machinery. After having convinced his head miller, they tried to persuade Pillsbury who, ‘After a good deal of talk he very reluctantly told us to go ahead and change the mill, and added, “Go quick, for fear I’ll change my mind”.’ (Gray, Part X, p.1243). The following day, the old machinery had been taken out of his Excelsior Mill and the new machinery put in. This machinery was proven to be a success and was eventually installed in all his other mills as well. So just as key men and companies were installing machines into big named companies in Britain, so they were also in America as W. D. Gray, with Edward P. Allis & Co., and John Stevens produced and installed machinery along with many others. The industry was growing both in Europe and America.

However, roller milling did not and does not solely exist in Europe and the United States. Countries throughout the world adopted the roller milling system and a selection of their histories can be read about in the following pages.

Sources:

‘Roller Milling: A Gradual Takeover’, From Quern to Computer: The History of Flour Milling.

Gray, W. D., ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling, Part II’, The Northwestern Miller (25 October, 1899), pp.799-800.

Gray, W. D., ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling, Part III’, The Northwestern Miller (1 November, 1899), pp.843-844.

Gray, W. D., ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling, Part X’, The Northwestern Miller (27 December, 1899), pp.1215 & 1243-1244.

Kuhlmann, Charles Byron, The Development of the Flour-Milling Industry in the United States (Boston, 1929).

Simon, Henry, ‘On the Latest Development of Roller Flour Milling’, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Vol 40 (1889), 148-192.

Walker, Graeme, ‘List of machinery in Caudwell Mill’ (2002): CAUD-06916.