Building a Mill: Construction

Once the location has been decided upon and the land has been purchased, thought naturally turns to the building itself. There are many factors to consider and works to consult in order to create a mill that fulfils the three main purposes of architecture, according to the author of ‘Hints on Mill Buildings’: to be useful, true and beautiful.

Layout

In order to get these results, it would make sense that the prospective miller would seek advice from the best possible sources in order to create a useful mill. Works they may have turned to include milling journals, such as The Miller, and text-books, such as those by Voller and Kick. On this issue of building a mill, these publications are all in agreements as to the first step: consult a Milling Engineer. Many millers had first gone to the architect, had the mill built and only then tried to fit the machinery into the available space. Rolls positioned too close together could be dangerous, such as at Chartham Mill, Canterbury, where the positioning of the rolls created ‘a dangerous mill in which to work, and I understand it was the cause of two bad accidents and the deaths of two millers’ (Hancock, p.6). Instead there should be ‘place for every machine and every machine in its place’, which there would be if ‘The Engineer selected to put in the roller plant…make out the plans for the building and not an architect’. Kick comments that this was the custom in Austria and that it should be copied elsewhere.

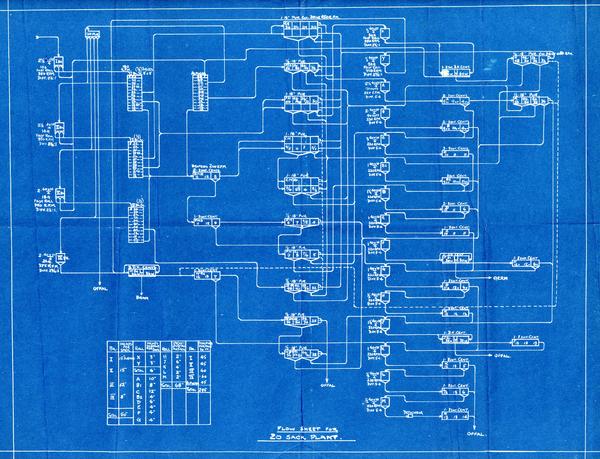

Once these engineers had been consulted, they would draw up a flow sheet, such as the one seen here. Flow sheets were ‘a graphic representation of the manufacturing system followed in a flour mill’ and would show the course different materials would take through the machinery (Voller, p.336). Once this had been drawn by said engineer and understood, attention could turn to the building itself.

The structure of the mill would vary depending on its size and capacity so no two mills would be exactly the same. However, general suggestions could be made about the form of the mill and the ‘Hints on Mill Buildings’ article gave some with the key points being:

- The mill should be oblong shape and not square.

- The mill should have at least four floors but five or six floors would allow for better arrangement of the machinery.

- The roller machinery, both the breaking and finishing rolls, should be placed on the first floor, as such the first floor should have the strongest beams.

- The purifiers should be placed on the second floor.

- The dressing machines and grading reels should be placed on the other two floors.

- Plenty of space must be left around the machinery to allow for easy access.

- Windows should be placed on both sides of the building to let in plenty of light.

This is one suggested way to build and structure a mill and would probably lead to good results. Other authors and publications may give alternative suggestions.

Role of the Architect

Once the interior has been sorted, the architect can still play a role in the fulfilling the third category of architecture, that of beautiful. Architects could approach mill buildings with as much creativity as they desired meaning that many different styles could be found in mill buildings. In Scotland, mills were frequently built in an Italianate castellated style; whilst throughout the rest of Britain, mills could frequently be found built in the Queen Anne revival style (including Victoria Mills in Grimsby and Foster’s Mill in Cambridge). These mills were imposing Victorian structures and could be used to show off the wealth of the owner and as such, could be very impressive.

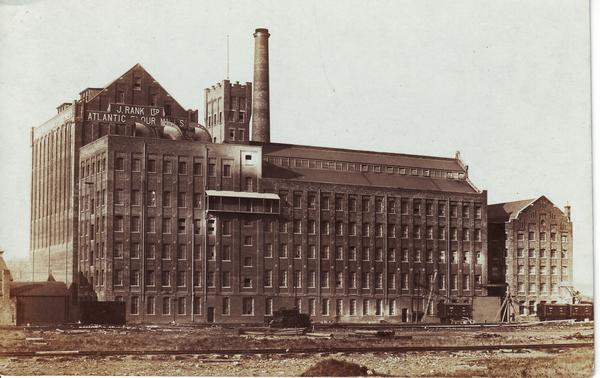

On the other hand, some owners just wanted their mills to be practical and did not care as much about how the building looked. One such man was Joseph Rank. His mills were exclusively built by the architect, Sir Alfred Gelder and his company, Gelder and Kitchen. Joseph Rank first asked his young friend and neighbour to build Clarence Mills in 1891 and this was the beginning of a long-lasting and fruitful partnership between the two. However, the architectural flourishes that Gelder included to complete the beautiful category of a building, were not appreciated by Joseph Rank. Instead, he is stated to have said: ‘Don’t have those twiddly bits put on the top next time – they’re no use to the mill; they’re only put there to help the reputation of the architect’ (Burnett, p.193). Clearly, not all millers cared about that final category and practicality trumped aesthetics.

Concerns About Fire

Whilst design and decoration of the mill may have fulfilled the third category of architecture, there is a fourth category pivotal to the world of milling not mentioned. That of being fire-proof. Fire was a great threat to mills, as can be read about here, so mill owners and mill designers, took precautions and preventions with, what one author called, an ‘obsessional interest’ (Clarke, 38). Mills were constructed to be fireproof which included ‘floors of concrete, granolithic paving, or some other of the numerous pavings of composite form now in the market’; window frames, doors, stairways, stairs and partitions made out of iron; and a flat roof supported by iron rafters with iron or steel girders (Voller, pp.400-401). Although Voller gave these recommendations, he does not promise that these precautions will prevent fires, surrounded as they were with combustible material produced by the machinery. Indeed, he actually states the opposite that ‘this expensive form of construction is practically as liable to destruction by fire as the less costly ordinary style’. (Voller, p.401) Therefore if fire prevention was almost impossible, an alternative approach had to be taken.

This approach was to contain fire, slow it, and extinguish it as soon as possible to save most of the mill. This was accomplished by using slow-burning materials and building large brick walls to separate parts of the mill with iron doors installed. This had the effect of helping to contain fire and prevent it spreading but it was the installation of sprinkler systems that played the key role of extinguishing the fire quickly. The installation of sprinklers was actively encouraged with the National British and Irish Millers Insurance Company, founded by Peter Mumford c.1892, only issuing policies to those sites with approved sprinkler installations with reduced rates. These automatic sprinkler systems and water-tanks, installed at least 10ft above the highest situated sprinkler, achieved success in containing fires and were credited for reducing the number of catastrophic fires.

So now you have a location chosen, a mill built following the directions of the milling engineer and architect with all the best precautions taken against fire. Now consideration must turn to the machinery as ‘such a mill could not fail to succeed if filled with an equally well-constructed automatic roller system of durable British-made machinery’ (once again according to the author of Hints on Mill buildings).

Read more about roller mill architecture in this blog post: Building a mill, without the twiddly bits

Sources:

‘Hints of Mill Building’ from Duffiled: 20.

Clarke, Jonathan, ‘Remnants of a Revolution: Mumford’s Flour Mill, Industrial Archaeology Review 24 (2002), 37-55.

Hancock, Philip, ‘Extracts from “Rambling Recollections of a Rural Miller”’ (1980): FULL-22162.

Pearson, Lynn, Victorian and Edwardian British Industrial Architecture (Marlborough, 2016).