From Field to Mill: Corn exchange

In Britain, one of the most important places for the milling industry was the corn exchange. This was a building where farmers and merchants traded corn. It was here where millers could go and buy wheat for their mill. It was of upmost importance that a miller was a good judge of quality as they needed the best wheat to produce the best flour. The best way to learn this was through experience, as Philip Hancock learnt when he worked for his father’s cousin, Mr. Hooker. During his third year with him, Philip was asked to accompany Mr. Hooker to the Corn Exchange on Saturday afternoons. He remembered how ‘Mr Hooker was a good judge of wheat’ and that

‘He would challenge me to judge the weight per bushel of the samples; a first class lot would weigh 62lbs or 63lbs per bushel, whereas a second class sample from about 58lbs to 60lbs per bushel.

After market we would return to the office and check the weights on a small brass weighing instrument which recorded the weight per bushel. I sometimes came fairly close to the correct weight but he usually beat me’ (Hancock, p.8)

Philip could not beat the experience of his employer but like many others, learnt from him and improved with time, a common experience in the wheat trading business.

Mark Lane Corn Exchange

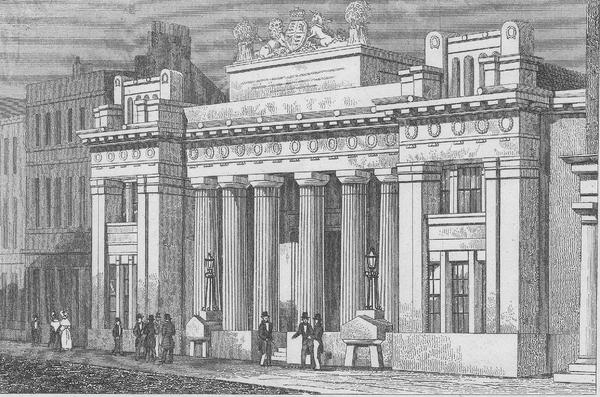

The most famous corn exchange in Britain was in London, the Mark Lane Corn Exchange. This Corn Exchange was first opened in 1747 and then another Corn Exchange was opened next to it in 1828. The Old Corn Exchange contained an open colonnade with modern Doric pillars whilst the New Corn Exchange was in the Grecian Doric style. It could house over eighty stands where corn-factors, merchants, and millers would all have stands with samples of their produce to sell.

The best descriptions of Mark Lane and the transactions that took place there, come from eye witnesses. Within different Victorian newspapers and journals, there are accounts of what life was like in the Mark Lane Corn Exchange. This article comes from The Daily Graphic, and was kept by William Duffield as a part of the Duffield Collection here at the archive:

‘The Corn Exchange has sturdily shaken itself free from the tangle of tradition and embarrassing custom. It lives under the stigma of no corruption and abuse. Its chief concern is to secure for the transaction of business convenience and simplicity. Any visitor may pass unchallenged through its doors, and mingle with the busy crowd, for the Corn Exchange is an absolutely free and open market; its authorities are prohibited by Act of Parliament from excluding any respectable person, or taking toll, except from sellers…

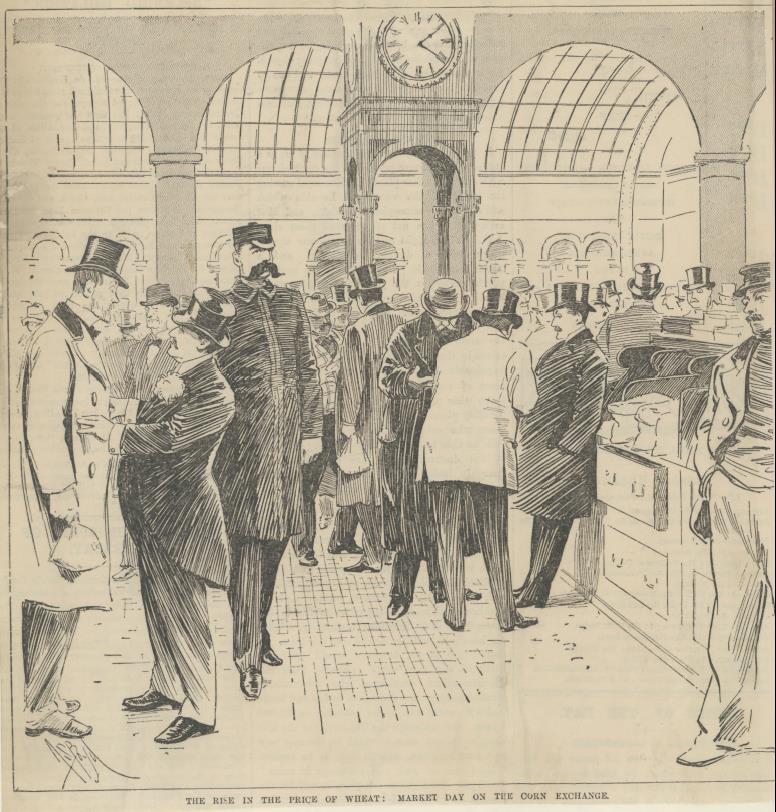

Business commences on market-days – on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays – at eleven, when a bell is rung. It grows in volume and excitement until half-past two, when the height is reached. Then the scene is busy and most interesting. It ranges from the prosperous London merchant, smart and stylish, with the suggestion of a public school training completed by a Bond Street tailor, to the sturdy country farmer, in pot hat and shooting-coat and gaiters, his pockets bulging with samples of grain. Here and there a bronzed and burly lighter-man, strayed from his quarters in the vestibule, elbows his way through the crowd; and the alert officers of the market move about with watchful eyes. There is very little noise. The floor is covered with small wooden blocks that deaden the sound of feet; the height of the roof mitigates the hum of conversation, and keeps the atmosphere clear and sweet. Round about the two lines of noble pillars that support the roof and elsewhere are disposed the stalls of the leading factors, laden with little bags and bowls of grain samples, and piles of oil cake. Wheat is the chief commodity dealt in – from India, the Danube, the Sea of Azov, the Black Sea, Eastern and South America, and Australia. There is maize from the Danube, the Black Sea, the River Plate, and the United States; barley from the Danube and the Sea of Azov; oats from Sweden, Russia, and Finland; rye from the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea; peas from Canada, and beans from Egypt and Barbary, Morocco and Saffi. Little groups of men turn over in the palms of their hands a few grains, smell them, blow on them, toss them in the air, and haggle over their price. The ends of the world meet indeed in Mark Lane…

In its secretary the Corn Exchange has a courteous and enlightened gentleman. In time gone by the beadle of the market used to be a person of much distinction and many perquisites. But he is shown of his pristine glory, and in his place there reigns a superintendent, without mention of whom no sketch of the Corn Exchange would be complete. He is a splendid creature, whose seven feet of height, deep in chest, and flamboyant moustache would distinguish him in a regiment of Potsdam giants. He has the responsibility of keeping the market clean and well ordered, and also of knowing every frequenter thereof – a dictator and a detective in fact, a watch tower and a fortress.

A few lines more may close the market and this article. At half-past two a bell rings once more, and for half-an-hour the outer door is barred against all incomers. This has the effect of gradually thinning the throng. At three the market is again thrown open, but few return. At four it is finally closed, and then given up to the sweepers. These are the servants of a contractor, whose annual payment for the litter of samples that strews the floor is a considerable source of revenue. On a busy day he takes away as many as fifteen sacks full.’

This gives a flavour of what the corn exchange was like and those who frequented the establishment. As can be seen from this description, and the accompanying images, the Corn Exchange was the domain of men, something Thomas Hardy took advantage of in his novel, Far From the Madding Crowd. He uses a scene in a corn exchange to develop the plot and character of the heroine, Bathsheba Everdene:

‘The first public evidence of Bathsheba’s decision to be a farmer in her own person and by proxy no more was her appearance the following market-day in the cornmarket at Casterbridge.

The low though extensive hall, supported by beams and pillars, and latterly dignified by the name of Corn Exchange…’ (Chapter 12)

So Bathsheba entered into this world of men and in typical fashion, charmed them and won them over. Although this is only a work of fiction, the inclusion of the Corn Exchange as a setting shows how important the institution was to the trade and that Bathsheba’s appearance there shows her to be a serious farmer.

Other Uses of Corn Exchanges

The inclusion of the corn exchange in Far From the Madding Crowd also serves to show how common corn exchanges were. Despite only having mentioned the famous corn exchange in Mark Lane, there were numerous other corn exchanges throughout Britain. The major port town of Liverpool had its first Corn Exchange building completed in 1808 and in nearly every town throughout the country, a corn exchange of some size could usually be found. Given the purpose of these corn exchanges, the buildings they were in were usually very large. This meant that other functions or gatherings could take place in them, for example, in 1884, William Gladstone, who was Prime Minister at the time, delivered a speech in the Corn Exchange in Edinburgh whilst the following year he gave another speech in the Corn Exchange in Dalkeith, Scotland. These public meetings in Corn Exchanges became even more common as the grain trade declined. Once the trade in these buildings finally stopped, there was an issue over what to do with these buildings given their vast size. Different places came up with different solutions and these buildings are now used for a variety of different functions: the Corn Exchange in Newbury is now a 400-seat arts centre; the one in Bristol houses St Nicholas Market, which was voted Britain’s best indoor market in 2016; whilst the corn exchange in Dalkeith, where William Gladstone gave his speech, is now a museum.

So, the Corn Exchanges which were once such an important establishment to the milling industry are no longer in use. Fortunately their buildings have survived to allow us to remember the important trade that took place in them.

Read more about Thomas Hardy’s work and its link roller milling, in ‘Thomas Hardy and the World of Milling’

Sources:

‘The Corn Exchange’, The Daily Graphic, Friday, 13 November 1896, p.8.

Hancock, Philip, ‘Extracts from “Rambling Recollections of a Rural Miller”’ (1980): FULL-22162.

Hardy, Thomas, Far From the Madding Crowd (1912).

Hooker, A. A., The International Grain Trade (London, 1939).

Platt, J. C., ‘The Corn Exchange’, in London Volume III edited by Charles Knight (London, 1842), pp.353-368.