Roller Milling Around the World: New Zealand

As in other countries, roller milling gathered momentum in New Zealand during the 1880s and 1890s. The first mill in the country to use roller machinery was built in 1882 and belonged to the Timaru Milling Company. Following this initial installation, many other mills began to install this new machinery. This was the second change the milling industry in New Zealand had faced in the space of 10 – 20 years as changes to the location of wheat growing regions in the country had led to a change in the concentration of mills, they declined in number on the North Island yet grew on the South Island.

Engineers

One aspect where New Zealand millers were similar, in the north and south, was in their choice of manufacturers to install the new machinery. Just like in Australia, most turned to foreign engineers, mainly British, with greater experience with the machinery. Whilst popular, British manufacturers were not the sole providers of machinery, as there are also examples of American machinery being installed in the country, J.C. Firth’s Eight Hour Mill in Auckland for example. The machinery in that mill was all American and installed by Messrs. Nordyke, Marmon, and Co. of Indianapolis.

One British firm credited with installing machinery in New Zealand mills was Thomas Robinson & Son of Rochdale. The Green Island Mill, Dunedin, belonging to Mr. H. Harraway had machinery installed by this Rochdale firm. Indeed, when re-modelling the mill in 1928-9, it was to this British firm they still turned to supply ‘the new machinery for the plant’ (‘Harraway and Sons, Ltd.’).

However, despite having some demand in New Zealand, Robinson was not the major supplier of machinery to the country. Instead, it was Henry Simon Ltd. of Manchester credited with that. By February 1889, six mills erected in New Zealand could be credited to Mr Simon, ‘These are situate at Auckland, Rangitikei, Temuka, Timaru, Christchurch and Palmerston.’ (‘A New Roller Mill, Messrs Wood Bros.’). By 1891 this number had increased to around fifteen, as can be seen on the map (right) produced by Simon, not including the partial installations that had also taken place. The majority of these installations took place on the South Island, although the North Island also had some installations too.

South Island

The map of Simon installations in 1891 shows a greater concentration of mill installations on the South Island, specifically in the regions of Otago and Canterbury, encompassing the installations in Palmerston, Oamaru, Timaru, Timuka, Ashburton, and Christchurch. These regions contained a high percentage of mills because from the 1870s onwards, this area became the principal growing region. The number of mills naturally grew to reflect this, particularly in North Otago and South Canterbury. Indeed, the growth in the number of mills in the region started before roller milling had even arrived in the country, as a newspaper article from 1873 reflects: ‘Mills are multiplying in this district; and it is not to be wondered at, seeing that it is the largest grain-producing district by far in the Colony. We have a windmill, steam-mills, and water-mills, and milling enterprise is evidently not yet at an end.’ (‘Local Industries: Teaneraki Flour Mills’).

Indeed, as the article stated, milling enterprise was not yet at an end in 1873, as the following example shows. The article described the recently erected Teanaraki Mills, Oamaru, owned by Messrs J. K. Anderson and Co., which contained two pairs of stones. The article described this mill as ‘well appointed, and…driving a good trade’, yet around four years later, in 1877, it was put up for sale (‘Local Industries: Teaneraki Flour Mills’). It was purchased by J.T. Evans & Co who decided that the Teanaraki Mill was too small given the rate the industry was expanding in the region. The new Crown Flour Mills were completed in 1878 with four pairs of millstones powered by steam. However, J.T. Evans & Co. did not long own this mill as John Evans and his partner, Charles Moore, soon both ended up in bankruptcy court and the mill was sold to brothers John and Thomas Meek. They then ran this mill and in 1886 decided to update it to the roller process on the Dell System. This change proved necessary as ‘they found they could not enter into competition with mills which had been fitted with rollers’ (‘Crown Roller Flour Mills’).

Therefore, by 1886 Meek’s Crown Roller Flour Mill was not the only roller mill in the region, given that their modernisation had been prompted by competition. Given that there were at least thirteen mills in the North Otago region, it stands to reason that some may have changed before the Meek’s. However, reports of other mills from the area suggest that the Meek brothers were actually earlier than many in installing this new machinery. Messrs Ireland and Co. had their flour mill in Oamaru fitted with roller mills in 1891; the mill that would become known as Clarks Mill had roller machinery installed in 1893; and the Ngapara Flour Mills, around 25km away from Oamaru, was built in 1898 as a roller mill. These examples all updated machinery in the 1890s, suggesting that Crown Roller Mills may have actually been one of the first in the region to change.

Mills were also being built and changing systems in the south in regions outside of Otago, particularly in Canterbury. In Timaru, in South Canterbury for example, there are records of ‘three large mills…the Timaru Milling Company, the Atlas Roller Milling Company, and the Belford Mills’, with at least Atlas Mill having Simon machinery installed. (Guide to Christchurch, p.179). A guidebook written for the Canterbury region in 1914 describes all these mills emphasising the recognisable flour brands that each mill produced: the Timaru Milling Company produced ‘Silver Dust’ flour; Belford Flour Mills produced ‘Golden Gem’ flour whilst Atlas Flour Mills produced ‘Atlas’ flour. They claimed that some of these brands, the ‘Golden Gem’ flour in particular, were ‘known as one of the best brands of flour throughout the length and breadth of the Dominion’ (Guide to Christchurch, p.255). This flour produced in the south was clearly sold in the north and competed with the flour produced there.

North Island

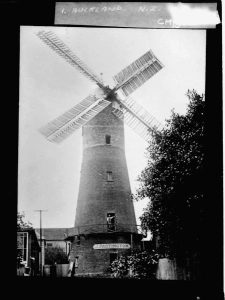

On the North Island, milling had diminished as the amount of wheat grown in the north lessened. Before the 1870s, the North Island produced the greatest amount of wheat in the country. The fields of Pirongia, Kihikihi, Kopua and Rangiaohia had been rich land producing up to 60 or 70 bushels an acre. Indeed, even up to the 1890s the north was still producing wheat in reasonable quantities. In 1894 the Auckland Province had around 9000 acres under wheat, producing an annual yield of about 24,000 bushels. However, from that time onwards wheat growing in the north truly did diminish as dairy farming became the main focus. Nevertheless, milling had been lucrative when the wheat fields were located there with many windmills and watermills built, the example here (left) was in fact described as one of the oldest landmarks in Auckland in 1920 showing its longevity. Some mills did survive through to the late 19th century and converted to roller machinery or new roller mills were built, such was the demand.

The main centre for mills in the north was in the city of Auckland where the Northern Roller Mill Co. operated from. It was formed in 1889 after the amalgamation of the Northern and Auckland Roller Flour Mills. Newspaper articles recording this opening reveal the struggle that the northern mills had against southern competition. The Auckland Star stated that this new mill ‘deserves the support of every loyal Aucklander. Why should we send so much money to the South for flour when we can get a better article for the same price at our own doors?’ (‘Northern Roller Mill’). Given that this company continued milling flour until 1992 and still exist today as a stock feed and premix manufacturer, the Auckland Star’s call for support was clearly heeded and acted upon.

The engineer Henry Simon had trade in the north as well as in the south, as could be seen on the earlier map. He installed machinery in cities other than Auckland in the north as well. One such installation marked on the map was in Marton, Rangitikei, where a three sacks per hour system was installed for the Henderson Brothers. Simon described this mill as ‘representative of the small country mill in New Zealand’ (Simon, 1892). Considering this small country mill had granaries capable of holding 16,000 bushels, it was not as small as may first be considered. Furthermore, it supposedly drew all of its supplies from the surrounding district, again showing that the north was not completely bereft of wheat growing areas.

Workforce

Working in roller mills often meant long arduous hours. Indeed, throughout the 1880s, most mills ran for 24 hours with two 12-hour shifts. The Oamaru Mail described these men working for 12 hours a day as being treated ‘like galley slaves’ (‘Daily Circulation, 1500’). To compensate for these long hours, some employers were then more generous in granting time off. Messrs. J. and T. Meek at Crown Roller Mill, Oamaru, for example. Their foreman wrote that employees at this mill were

‘allowed a half-holiday every alternate week; also Christmas and Boxing Day, the first and second day of January, Good Friday, and Queen’s Birthday; also two half days at the show time; and, in addition to the above, one week’s holiday or pay equivalent each year; and, if at any time the men have been asked to work on recognised holidays they have been paid double time.’ (‘The Crown Mills Employees’)

Along with this he claimed that the workers at this mill received the ‘highest rate of wages in Oamaru’ and that there was a good feeling between Mr Meek and his employees.

Despite receiving some compensation for their 12-hour shifts, workers still campaigned for a reduction in shift length to 8-hours, something the Oamaru Mail did support, to a certain extent, so men could ‘have some pleasure in life and be able to attend to their paternal responsibilities’.

Whilst the Oamaru Mail was writing about the possibility of eight-hour shifts, there was already at least one mill in the country following that method. Josiah Clifton Firth established a fully automated mill on Auckland’s Quay Street in 1888. It was known as the ‘Eight Hours Roller Mill’ such was the novelty of a mill working on an eight-hour rather than 12-hour shift system. Unfortunately, only a year after opening, Firth was declared bankrupt and his mill was sold ‘on behalf of the mortgagees, the Bank of New Zealand and the New Zealand Loan and Mercantile Company’ (‘Eight Hours Roller Flour Mill’, p.5). A Mr. Douglas purchased the mill yet chose to mainly keep on ‘the fine body of men whom Mr Firth gathered round him’. Whilst no job was certain, these men, at least, were given a reprieve in having to search for a new position and as it became the mill for the Northern Roller Milling Company, these workers may never have had to worry about finding a new position.

The milling trade in New Zealand entered the 20th century in a strong position. However, numerous changes took place throughout the 20th century creating the industry that can be seen today.

Wheat Growing

One major change that took place in New Zealand was the change in farming habits. New wheat varieties were introduced to the country, meaning North Otago lost its position as the best wheat-growing region. The loss of wheat from this area also led to a decline in the number of mills in the region, by 1940, only four mills remained in North Otago: Meek’s Crown Flour Mills and Ireland’s Mill in Oamaru; Clark’s Mill in Maheno; and Milligan’s Mill at Ngapara (McDonald, p.240).

Furthermore, wider farming habits throughout the country were changing, as meat and wool became more attractive propositions than wheat. This meant that the amount of wheat grown in the country generally declined. Indeed, by ‘1930 the area in the country devoted to wheat-growing was down to 16,000 acres and by 1939 to 10,000, less than a third of the land used forty years earlier’ (McDonald, p.240). This led to a greater reliance on imports of both wheat and flour from Australia, creating competition with local products.

Quota System

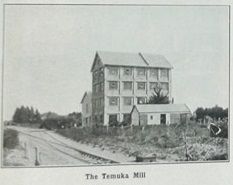

Another major change in the New Zealand Flour Milling Industry, possibly partly prompted by changes in farming, took place in 1936. During this year, a quota system was introduced, meaning the government set the amount of flour a mill could produce. Other regulations were also introduced, including price control and restrictions on imports, along with the creation of the Wheat Committee, in charge of supplying wheat to millers. These regulations lasted until the 1980s with the quota system finally ending in 1987. During the fifty year period it was in place, quotas remained fairly stable, indeed, data collected by Peter Allport charted the allocation of quotas from 1936 to 1982. The Temuka Milling firm were allocated 1.37% of the total flour trade in 1936, in 1982, they were again allocated 1.37% of the total flour trade. This was the only example of a mill allocated the same quota in 1936 as in 1982, other companies had greater variations. Zealandia in Christchurch, for example, was allocated 3.26% of the total trade in 1936, this percentage fell to a low of 2.91% in 1976 but then rose again to 6.40% in 1982.

Despite this regulation causing relative stability within the trade, it was also responsible for some detrimental effects on the trade. Capacity rates from the 1930s were maintained over 50 years. Advancements and efficiency were therefore not encouraged, and mills frequently ran at less than their capable capacity. Many mills did not survive and between 1936 and 1966, over half of all mills closed down (Pickford, p.5). Those that did survive often went through changes in ownership, such as Meek’s Mill in Oamaru which was taken over by the Ireland Group in the 1960s. Changes were therefore taking place throughout this period of ‘stability’ for the trade.

On the other hand, some areas of the trade, such as wheat growing regions and price, remained the same. However, this was not necessarily good for the trade either. The price of wheat was controlled and maintained at a low price. As such, the majority of wheat was grown in areas ‘where the costs of production was lowest’, which continued to be in the South in areas around Canterbury (Pickford, p.5). This practice was followed ‘regardless of quality and of proximity to markets’, so encouraged inefficient transport patterns (Pickford, p.5). Indeed, the South Island, containing one-third of the population, produced two-thirds of the flour for the country. The North Island, with two-thirds of the population, only produced one third of the flour. As such, around 40,000 tonnes of flour was shipped annually from the South Island to the North Island (Pickford, p.5). Given that greater amounts of wheat were also grown in the South, this product was sent in large quantities to the North Island too.

Both the wheat farmer and flour miller were therefore guaranteed custom, be it in the South or North Island. However, this removal of competition, and the introduction of price fixing, was ultimately detrimental to the quality of products. Wheat farmers were under no pressure to produce high quality crops; neither were flour millers under any incentive to produce higher quality flour; it was therefore the bakers that ‘suffered from flour that was often unsuitable, and whose quality varied’ (Pickford, p.5).

These issues, and others factors, led to the deregulation of the industry, starting in 1984. This removed quotas and price fixing, allowed millers to purchase wheat direct from growers and relaxed restrictions on Australian imports. Australian wheat was ‘more consistent’ and of a ‘higher quality’, which meant many New Zealand millers favoured these imports over home-grown wheat (Pickford, p.8). During the 1990s, around 200,000 tonnes of wheat was imported annually. This process of deregulation would prompt further changes to take place within the industry, creating the industry in place today.

Post-Regulation Period

As a result of deregulation, a trade which had been ‘locked in a time warp’ experienced ‘a rash of firm closures, amalgamations, and takeovers’ as the ‘pent-up changes accumulated over many years occurred very quickly’ (Pickford, p.10). As such, three firms, Defiance, Goodman Fielder, and Allied Foods, attained dominant positions in the industry.

Defiance Food Industries was owned by the Australian Company, Defiance Mills. They opened their first sales office in New Zealand in Auckland in 1986, probably encouraged by the prospect of deregulation. After purchasing the Ireland Group in 1987, it owned mills in Mount Maunganui, Christchurch, Oamaru and Dunedin. They closed the Oamaru mill down but continued milling in the other three, along with acquiring bakeries in other cities.

Goodman Fielder, meanwhile, was founded when the Goodman Group acquired the Australian firm Fielder Gillespie, in 1986. They owned mills in both the North and South Islands and in 1997, they acquired the mills owned by Defiance, reducing the number of dominant firms to two. They continued milling in Mt Maunganui and Christchurch until 2012 when the firm decided to sell their ‘Champion Flour Milling’ business and focus on their other products. The flour business was purchased by the Japanese firm, Nisshin Flour Milling, for $51 million and continues milling today.

The third important firm that gained dominance during this period was Allied Foods. Allied Foods was a subsidiary of George Weston Foods Ltd. and entered New Zealand in 1951, when it started acquiring bakeries. Then in 1978, they started acquiring flour mills when they purchased 50% of Auckland Flour Mills, the other 50% was gained in 1988. A presence in the South Island was secured in 1991. Today, the firm still exists as Weston Milling and has three mills throughout New Zealand in Oamaru, Christchurch, and Auckland. In 2014 Weston Milling merged with AB Mauri Australia/New Zealand, but as both firms are owned by Associated British Foods, the overall ownership of the firm has not altered.

Therefore, out of the three dominant flour milling firms from the 1980s, two are still working today, although only one is still producing flour. However, they are not the only firms or mills still working in New Zealand today. The Milligans Food Group, based in Oamaru, sells many products, including flour and feed produced by the Milligans Eclipse Flour Company, whilst the Farmers Mill in Timaru claims to be the ‘only independent grower-owned and operated flour producer in the country’ (farmersmill.co.nz). Imports of Australian flour also contribute to the market.

Furthermore, the history and heritage of the early days of roller milling have not been ignored. Clarks Mill in North Otago is the only surviving water-powered flour mill in New Zealand and contains original roller machinery. This mill is now opened to the public and the machinery itself can be seen working on certain days. So the history of the flour trade from the 19th century has been preserved whilst the modern industry continues to produce flour today.

The Mills Archive is grateful for information provided by Mr. Bryan McGee, Mr. Richard Eliott, and Mr. Peter Allport, in aiding with the completion of this article.

Read more about the image and postcard of Partington’s windmill in this blog post: ‘Detective Work from the UK to New Zealand’.

Sources:

*Image of Northern Roller Milling Company building, Quay Street, Auckland. Auckland Star: Negatives. Ref 1/1-002903-G. Alexander Turnball Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22995620* http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22885620

‘A New Roller Mill, Messrs Wood Bros.’, Press, Volume XLVI, Issue 7232 (9 February 1889), p.6.

‘Abundant Food Reaped from a Friendly Soil: Treasure Below the Surface’, New Zealand Herald Supplement, (22 January 1940), p.75.

‘Crown Roller Flour Mills’, North Otago Times, Volume XXI, Issue 6057 (20 May 1886).

‘Daily Circulation’, The Oamaru Mail, Volume XVII, Issue 5267 (6 May 1892), p.2.

‘Eight Hours Roller Flour Mill’, Press, Volume XLVI, Issue 7375 (30 Jul 1889), p.5.

‘Harraway and Sons, Ltd.’, Otago Daily Times, Issue 20746 (18 June 1929), p.23.

‘Local Industries: Teaneraki Flour Mills’, North Otago Times, Volume XVIII, Issue 825 (18 April 1873), p.2.

‘Northern Roller Mill’, Auckland Star, Volume XX, Issue 198 (21 August 1889), p.5.

‘The Crown Mills Employees’, Oamaru Mail, Volume XVII, Issue 5271 (11 May 1892), p.3.

Borough Councils and Local Bodies of Canterbury, Guide to Christchurch and Picturesque Canterbury, (1914).

http://www.flourinfo.co.nz/index.php/about/flour-mills-in-nz accessed on 03.01.18.

http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/2285 accessed on 02.08.17.

https://nzplaces.nz/tags/Flour-Mill accessed on 03.01.18.

Simon, Henry, The Present Position of Roller Flour Milling (Manchester, 1892).

Tolerton, Jane, ‘Agricultural processing industries – Grain processing from the 1880s’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand https://teara.govt.nz/en/agricultural-processing-industries/page-6 (accessed 3 January 2018).

*Image of Champion Flour Mill from NZFMA website*

‘Nisshin to buy Goodman Fielder NZ flour milling business’, World Grain News (December 7, 2012).

Dr Michael Pickford, ‘Wheat Growing, Flour Milling and Bread Baking, A case study of a domestic agricultural industry adapting to overseas competition’, NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper No. 4 (1999).

http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/2285 accessed on 02.08.17.

McDonald, K. C., White Stone Country: the story of North Otago (1962).

Tolerton, Jane, ‘Agricultural processing industries – Grain processing from the 1880s’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand https://teara.govt.nz/en/agricultural-processing-industries/page-6 (accessed 3 January 2018).