Roller Milling Around the World: Ireland

The early stages of the history of roller milling in Ireland is similar to that of Great Britain due to its proximity and the fact they faced the same issues. The biggest issues were the greater demand for white bread and the large imports of cheap American flour made using the ‘New Process’. This presented a serious issue for the Irish miller who had been in a lucrative business until the mid-1870s. Now their livelihood was under threat from imported American flour. A response had to be made.

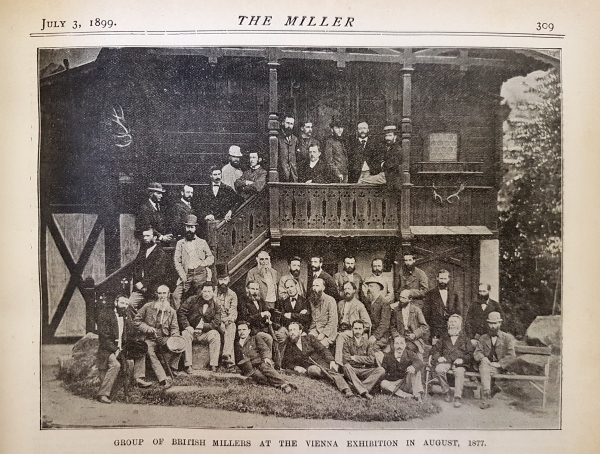

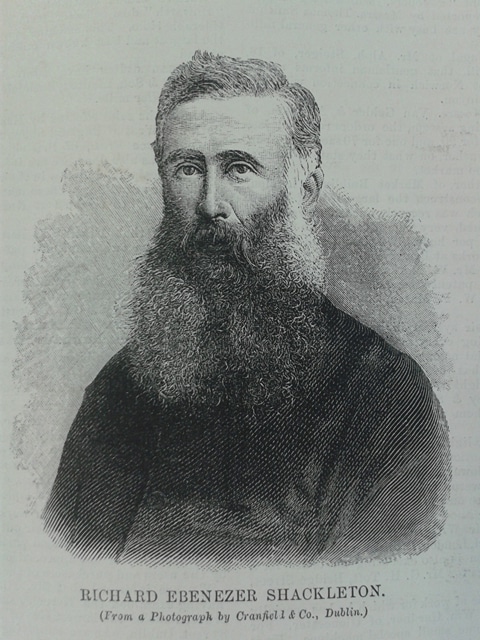

This response started in 1877 when, along with other British millers, a group of forty visited Vienna and Budapest to view the ‘Hungarian Method’. On this trip there were around eight Irish millers including Richard Shackleton; J. R. Furlong; D. Carmichael; and J. W. McMullen. The first of these men to act and have a roller system installed in their mill, was Richard Shackleton. In 1879 Henry Simon received an order for roller machinery for Messrs E. Shackleton & Sons mill in Carlow, and subsequently, for their mill at Athy. This was the first example of rollers in Ireland but J. Harrison Carter was not far behind Simon as he installed what was considered the ‘first roller mill in the world which finished off all the products in one continuous operation’, in 1880 in the Ringsend Road Mill of the bakery firm of Patrick Boland (Jones, 2003, p.113).

Over the next twenty years, Irish millers embraced the roller process as more and more installed the machinery into their mills. Other changes were also made due to this new machinery. For example, in the early 1880s, Andrews transferred their flour interest from Comber, Co. Down, to Belfast where they chose a port location. This move gave them quicker and cheaper access to imported wheat and a large customer base for their product.

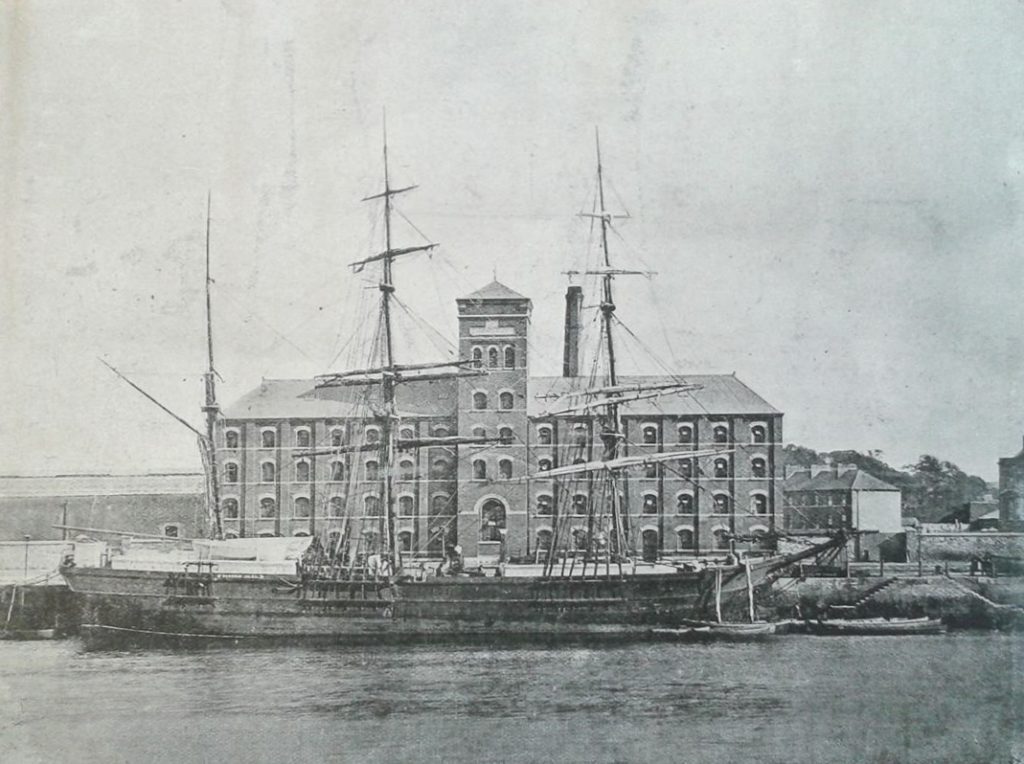

The move was successful and this company still exists today as Northern Ireland’s only independent flour milling company. Meanwhile, Furlong and Sons Ltd., the same Furlong who had visited Vienna in 1877, had a custom-built roller mill at Marina Mills established in 1891 (see picture above) whilst their mill on Lapp’s Quay was also installed with 19 sets of rollers.

Engineers

Throughout Ireland the roller milling industry was growing. According to a report by nabim in 1887, out of the 461 complete Roller Process Mills in the United Kingdom, 73 were located in Ireland (Jones & Tann, p.64). The main companies who installed the plants in these early days were the two already referred to: Henry Simon Ltd. and J. Harrison Carter. By 1885, Henry Simon had installed 37 roller plants for 25 different companies, the locations of which can be seen on the following map (Jones, 2003, p.116). Some places had multiple installations with the green point on the map referring to 4 different Simon installations; the red locations had 2 installations whilst the blue points only had one installation during this period. Simon’s business continued to grow and by 1936, Simon Ltd. claimed that 75% of flour produced in the Irish Free State was produced by Simon plants (Bielenberg). However, during the 1880s, Simon Ltd. was faced with the strong competition of J. Harrison Carter. Indeed, by 1886 it was the Carter system that was more prominent in Dublin, not the Simon system. However, Carter retired in the late 1880s and it was Thomas Robinson & Son who then grew in popularity in Ireland.

Ireland was important for Henry Simon for more than just custom, an important employee was hired by the company from the Irish Milling industry. This employee was William Stringer. He had been in charge at Shackleton’s Carlow mill in 1880 when the new roller system was installed by Simon’s, with Henry Simon himself superintending the operation. He was impressed with Stringer despite not being a professional engineer, rather a ‘star performer(s), enthusiastic, industrious and fallible’ with ‘substantial practical experience’ (Jones, 2001, p.185). He was then hired to work for Simon Ltd. in 1881 and became the ‘principal milling expert’ for the company (Jones, 2001, p.184).

20th Century

So, by the time they reached the 20th century, the situation for Irish milling was improving. Indeed, an article from The Miller in 1903 paid tribute to the fight of the Irish millers:

‘Irish millers have for a long time been famous both for proficiency in their craft and also their plucky efforts to compete not only with the large mills in this island, but also against the great imports of American flour, and a fine fight they have made, and are still making. We are certainly filled with admiration in noticing the indomitable courage and commercial enterprise as displayed by these gentlemen’

As regards the case of imported American flour, they could even be seen as winning that fight as the amount of imports ‘rapidly declined’ from 1903 onwards (Bielenberg). It is true that many mills did close down in this period and they were mainly ‘those who failed to adapt’ meaning that ‘flour production…became more concentrated in the hands of those who had adopted roller mills’ (Bielenberg). For example, in Limerick, trade was concentrated in two large companies: Bannatynes and Russell’s who then had depots throughout Munster and Connaught.

This meant that the situation pre-WWI was relatively good, although there were some serious concerns about overcapacity. The outbreak of war meant that the ‘government controlled the purchase of wheat, its manufacture and the sale of flour’ (Takei, p.134). However, post governmental control, overproduction became a serious issue in Ireland and the U.K. This was exacerbated in Ireland as surplus British Flour was ‘dumped’ on the Irish market and local mills could not afford to keep running. Indeed, the Irish Flour Millers’ Association, founded in 1902, sent a report to the government in 1926 asking for protection as they explained ‘the critical situation in the national industry’ (Takei, p.135). This overproduction and lack of protection caused more mills to close and create the landscape that Elizabeth Bowen described in her work, The Shelbourne: ‘those great abandoned mills which, all over Ireland, gauntly stare down the river valleys’ (Bowen,). The figures also show this decrease as in 1918 there were an estimated 44 mills whilst by 1932, there were only 28.

However, this situation changed with a change of government. In 1932 the Fianna Fáil government came to power with their programme of encouraging ‘native manufacturing’ and becoming self-sufficient (Takei, p.140). They introduced a tariff on imported flour and flour millers were not allowed to operate without a licence. Quotas were set and the number of flour mills in production actually increased to 37 in 1936. This period also saw another change take place as large companies started gaining controlling interests in smaller mills. The main examples were Ranks and the Dublin Port Milling Co. Ltd. with their ally, the Odlums Group. Odlums was a family company that had existed since the 1800s with their main mill at Portarlington having been built in 1880. It was Odlums that would prove to be of greater longevity out of the two and built its own milling empire.

Second World War and After

The milling industry in Ireland coped well during the Second World War with the government setting up a Wheat Reserve Committee and Irish Shipping Ltd. to import the grain. It was only post-war that rationing was introduced, but due to the greater shortage of other products, flour consumption was actually 20% higher than it had been pre-war. Flour and bread was subsidised and this continued until 1957. By that time, flour consumption in Ireland was beginning to decline as diets became more diversified. This led to a reoccurrence of overproduction that caused Irish Flour Millers’ Association to run a voluntary rationalisation programme prompting many mills to be taken out of production. This meant that by the end of 1965, there were only 17 mills in operation: Odlum’s Group owned 7; Rank’s owned 4, whilst there were still 6 independent mills.

The closure of mills and consolidation of bigger companies continued through the 20th century as Rank’s closed both their Limerick Mills and their Pacific Mills in Belfast during the 1980s. Odlums, however, continued and are still producing flour today. With the recognisable Odlum Owl logo along with their motto, ‘Bake with the Best’, their custom has continued throughout the years and led to a successful business. Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, Andrews Flour acquired Mortons Flour during the 1980s, and now produces both brands, whilst James Neill Ltd. became part of Allied Mills in 1962, and still produce Neill’s Flour.

Irish roller milling has therefore changed a lot since its inception during the 1880s. It survived two World Wars but it was the larger issue of overproduction that arguably caused the greatest changes to the industry during the 20th century. Today, although in lesser numbers than in previous years, mills can still be found throughout Ireland that produce the flour that can be found on supermarket shelves.

Sources:

*Image of Odlums Mill, Cork, © glassey alley 2009*

*Images of Bannatyne Mills, Limerick Docks, Kieran Clancy © 20/7/12 Copyright Kieran Clancy / PicSure Ltd © 2012*

Bielenberg, Andy (ed.), Irish Flour Milling: A History 600-2000 (Dublin, 2003).

Bielenberg, Andy, Ireland and the Industrial Revolution: The impact of the industrial revolution on Irish industry, 1802-1922 (Abingdon, 2009).

Campion, Norman, ‘Irish Flour Milling Since the Second World War’, in Andy Bielenberg (ed.), Irish Flour Milling: A History 600-2000 (Dublin, 2003), pp.155-177.

Jones, Glyn & Tann, Jennifer, ‘Technology and Transformation: The Diffusion of the Roller Mill in the British Flour Milling Industry, 1870-1907’, Technology and Culture, Vol 37, No. 1 (January, 1996), 36-69.

Jones, Glyn, ‘The Introduction and Establishment of Roller Milling in Ireland, 1875-1925’, in Andy Bielenberg (ed.), Irish Flour Milling: A History 600-2000 (Dublin, 2003), pp.106-132.

Jones, Glyn, The Millers: A story of technological endeavour and industrial success, 1870-2001 (Lancaster, 2001).

Takei, Akihiro, ‘The Political Economy of the Irish Flour-Milling Industry, 1922-1945’, in Andy Bielenberg (ed.), Irish Flour Milling: A History 600-2000 (Dublin, 2003), pp.133-154.

The Miller, 2 February 1903.