Roller Milling Around the World: Canada

Before roller machinery became used in the milling industry worldwide, the United States was producing ‘New Process’ flour, made by using a purifier to help break down the flour into finer, higher grades. As Canada is located next to America, it was in an ideal location to benefit from the mechanical advancements taking place in that country. Indeed, the La Croix brothers, credited as building one of the first purifiers in the U.S., were working in Montreal when Faribault hired them to build his mill. This location, and the fact Canadian flour was sold to European markets, made it inevitable that Canadian millers would have to adopt the new system to be able to compete on a worldwide market.

Elements of the ‘New Process’ from America were installed into Canadian mills, which then produced higher grade flour. However, this higher grade flour was not necessarily welcomed in Canada. Due to there being no tariff on American flour coming into Canada, low grade American flour was dumped on the Canadian market whilst high grade flour was sold at higher prices in America. The Canadian population preferred this cheap, low grade flour over expensive, high grade flour. As James Goldie commented in 1876, the Canadians had not been educated to buy higher grade flour at higher prices. The Canadian millers could not make a profit by exporting this high grade flour to America either, as they had to pay a tariff of 20 per cent per barrel. The laws had to be changed to protect the Canadian millers.

The first change came about in 1879 when, after years of complaints and hard work by the Dominion Millers’ Association, a tariff was introduced on American wheat and flour. This consisted of 15 cents per bushel of wheat and 50 cents per barrel of flour. These tariffs were often viewed as inadequate yet were not changed until 1891 when the price per barrel of flour was raised to 75 cents. Nevertheless, it was a start and this protection for Canadian millers encouraged many of them to try new roller machinery.

Pioneers

One of the first families to experiment with roller machinery, was the Snider family. From 1875-1877 Austrian rolls were installed in E. W. B. Snider’s mill at St. Jacobs, Waterloo County. Some adaption had to be made to this machinery as Canadian mills were automatic, whilst European mills were not. This led to some difficulties and helps explain why most other mills that installed roller machines during these early days imported them from America. The installations at this mill happened secretly, indeed, there were no reports of it being a roller mill until 1881 as they feared the innovation would be frowned upon. However, engravings on the wall of the mill survived to date the earlier installation of the machinery. Therefore, it appears that the credit for being the first to ‘successfully adapt to roller milling in Ontario in 1870s’ must be given to E. W. B. Snider (Leung, p.193).

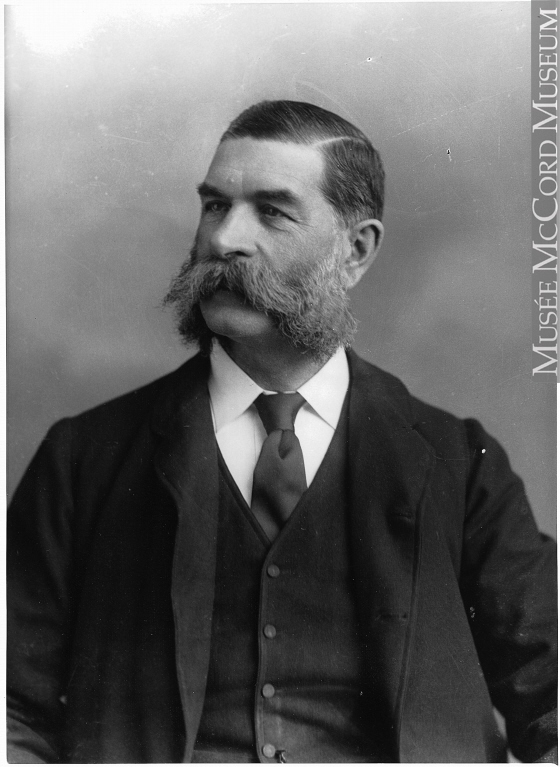

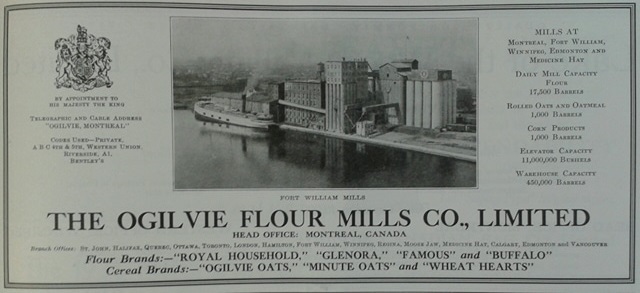

However, whilst he may have been the first in Ontario, Snider may not have been the first to experiment with roller machinery in Canada. In Montreal, the flour milling business A. W. Ogilvie and Co. could be found. In 1868, Alexander Walker Ogilvie along with his brother, William Watson Ogilvie (see picture, above), visited Hungary to view roller machinery. After this visit they supposedly installed roller machinery into their mill and one author records that in ‘1871 A.W. Ogilvie reportedly imported a set of rollers from Hungary’ but follows this comment up with the fact that ‘little is known about these’ (Leung, p.187). Therefore, although details are limited, it is clear that a number of individuals imported roller machinery during the 1870s and 80s. Many installed partial systems with rolls doing the initial break, but millstones were used for the reduction of the middlings.

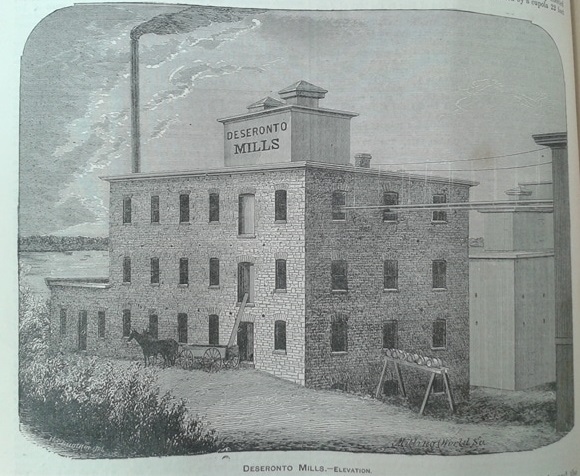

There are also many candidates for being the first to have a complete roller mill system in Canada. The Canadian Miller claims that ‘To the Rathbun Company, of Deseronto, Ont., is to be given credit for planting the first roller process mill in Canada’ when they built a 150 barrels per day capacity mill in 1881 (‘The Deseronto Mills’, p.5). It was powered by steam and secured good rates for Manitoban wheat bought from across the country. However, this was not the only mill to have a full roller system installed in 1881. E. W. B. Snider was credited as having a ‘full roller mill’ in his Dundee mill, installed by the Goldie and McCulloch Company of Galt, by 1881 (Hilborn, p.78). Furthermore, John Goldie of the Goldie and McCulloch Company was not the only Goldie family member involved with roller machinery installations in 1881.

Goldie Family

In 1844, John Goldie with his wife, two sons and four daughters, left their native Scotland and moved to Canada, two years after his two eldest sons had immigrated to America. In 1848 he built an Oatmeal mill in Ayr, and a year later, constructed a flour mill on the site of his old sawmill. This Greenfield Mill would be one of the mills installed with the roller process in 1881, although it is his sons who have to take most credit for this.

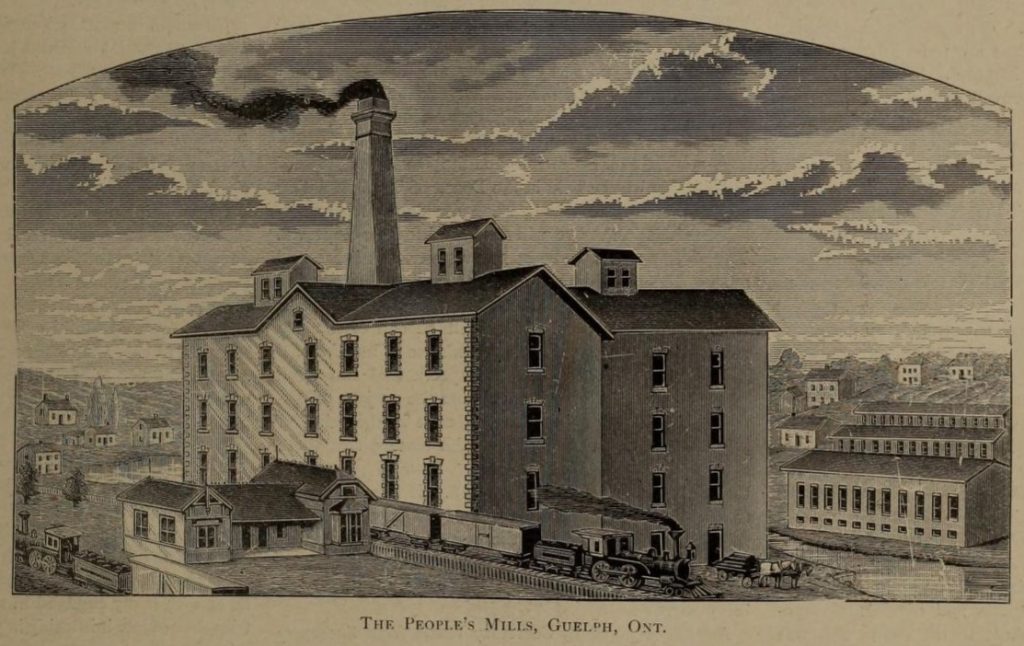

John Goldie’s four sons all ended up involved in the milling industry. His eldest sons, James and William, moved to the United States in 1842 where both worked in a variety of jobs. After the rest of the family moved to Canada, William joined them in helping build Greenfield mill. James did not move to Canada until 1960 when he built Speedvale flour mill in Guelph with William. After this partnership ended, James built the People’s Mill in 1867, which, by the time The Canadian Miller published an article about it in 1892, was working on a full roller system with a capacity of 500 barrels per day.

Meanwhile, back at the Greenfield Mills, David Goldie had taken over the running of the mill from his father, so would have been in charge when the roller machinery was installed. The installation of this machinery and the fact that ‘Since 1881 no year has passed without some new machinery being added to the plant’ was no doubt helped by the fourth brother (‘Greenfield Mills’, p.9). John Goldie Jr. formed a partnership with Hugh McCulloch in 1859 and this Goldie and McCulloch Company receive the accolade of being the first Canadian company to take out a patent on the roller milling process on 21 June 1883. They had manufactured and installed the machinery into Snider’s mill two years earlier and this side of the business continued to grow and flourish, aided by the hiring of foreman J. E. Wilson in 1886 who was ‘known as a milling expert in his day’ and ‘was responsible for arranging many of the roller systems in Ontario’ (Leung, p.209). He began this arranging of roller systems as soon as he was hired in 1886. He oversaw the installation of roller machinery into Mr. J. S. Plewes mill at Shelburne, Ont. One piece of machinery that was installed there was a dust collector that had been ‘recently…introduced, and is the invention of Mr. Wilson, who has had the machine recently patented’, highlighting the value that Mr. Wilson bought to the firm (‘Shelburne’s New Roller Mill’, p.49).

The Goldie family and their mills did not have as big an impact on the milling industry in Canada as some other individuals and families, for example the Ogilvie’s who in 1894 could claim that ‘the output of the various mills under Mr. Ogilvie’s control’ was ‘the greatest controlled by any one man on this continent’. Nevertheless, they were part of the original pioneers of the industry in using roller machinery and John Goldie Jr., with Hugh McCulloch, was responsible for installing much of this machinery in Ontario. They, along with many others made up ‘the pioneers of roller milling…whose energy, money and experience was spent not only for their own benefit, but for the benefit of those who followed and profited from the pioneers’ mistakes as well as their success’ (Leung, p.193).

20th Century

Roller milling was well established in Canada at the turn of the century and millers were annually exporting over 80,000 tonnes of flour a year. However, the issue that the flour milling industry was facing in other countries soon affected the Canadian milling industry too; the issue of over-production leading to competition between the mills. Rationalisation methods were introduced as mills were amalgamated or closed. The Goldie family at Greenfield Mill was not immune to this. Given their earlier success, the family had expanded their business and purchased two more mills, one in Galt and one in Highgate. However, as part of the general rationalisation, they sold all three mills to the Canadian Cereal Company in 1911.

In contrast to this, the wheat industry was thriving. The extension of railways from the Prairies in the west to the ports in the east allowed the good quality and highly demanded Canadian wheat to reach foreign buyers. The Ogilvie Milling Company, already a leading mill company, became a leading figure for grain elevators as well and Ogilvie Flour Mill elevators could be found throughout the country, storing grain ready to be transferred and transported across the country.

The events in Europe during 1914-1918 affected Canada as part of the Commonwealth. Men joined the fight whilst international demands for wheat and flour increased. However, according to the Canadian War Museum, the expansion of wheat exports and growth in areas farmed hid more serious problems: ‘on the wheat-producing Prairies, where heat, drought, frost, and soil exhaustion during the war reduced output per acre even as the size of farms expanded’. Nevertheless, in general, the Canadian wheat and flour industries flourished during the war and immediately afterwards.

Despite this brief respite, the industry was once again struggling by the 1920s. The high foreign demand for produce during the war had ended. One report from Ottawa suggested that the United States had purchased 198,968 barrels of flour in March 1921 whilst in March 1922, they had only purchased 71,063 barrels. The number of mills in the country had already dramatically declined from 1891, when there had been 2550 mills, whilst in 1922, there were 801. Those left were turning to advertising to deal with the loss of demand and consumption. Indeed, it became to be seen as pivotal for survival as in 1921, 86 per cent of business failures were by firms that did no advertising. So through rationalisation and advertising, the industry survived the 1920s.

Following on from those difficulties, the Great Depression of the 1930s hit the miller’s hard. However, one bakery firm appeared to be immune from these difficulties: George Weston Limited. By the 1930s this company was being run by Willard Garfield Weston (image above), the son of the founder. He had been involved in the company for many years and had successfully launched Weston’s English Quality Biscuits in 1922. When the Depression hit, Weston was able to buy up other bakeries that had been hit hard by the Depression, stating that these ‘wonderful bargains’ were too good to miss. His second major expansion during these years was to buy bakeries in Britain to become part of his Weston firm. His motivation behind this was to create a greater demand for Canadian wheat and flour, which he would use in these British bakeries, to help the struggling Canadian firms hit by both the Depression and drought. This tactic was a success and the Weston bakeries in Britain grew in number under the name of Allied Bakeries Limited, now Associated British Foods. He expanded into flour milling in Britain during the 1960s too. This move was prompted by the knowledge of the levy that would be imposed on Canadian flour once Britain joined the EEC, which took place in 1973. The last flour exports from Canada for these British bakeries took place in 1968 whilst the Canadian branch continued to thrive and diversify.

Weston developing a milling industry in Britain highlights another issue that Canadian millers faced in the latter half of the 20th century, namely the issue of exports. The number of exports greatly reduced during this period meaning more mills were taken out of operation. In 1997 Canada was only recorded as having 27 flour mills, 12 in Ontario; 4 in both Québec and Alberta; 3 in Saskatchewan; 2 in Manitoba and only one each in British Columbia and Nova Scotia. Despite this decrease in the number of mills, the high quality of Canadian flour is still sought after and it is still exported throughout the world today. The work and legacy of those early pioneers has endured.

Read more about David Goldie and his ‘Roller Milling Romance’, here.

Sources

*Image of Garfield Weston from https://garfieldweston.org *

*Image of W. W. Ogilvie, Image II-87527 from McCord Museum*

‘Advertising as a Business Safeguard’, Canadian Milling and Grain, Vol. II, No. 11 (1 July, 1922), p.14.

‘Canadian Flour Mills: Shelburne’s New Roller Mill’, The Miller, (5 April, 1886), p.49.

‘Flour Exports to U.S. Declining’, Canadian Milling and Grain, Vol. II, No. 8 (15 May, 1922), p.22.

‘Greenfield Mills’, The Canadian Miller, (January 1892), p.9.

‘The Deseronto Mills: History of the First Roller Process Mill in Canada’, The Canadian Miller, (January 1892), p.5.

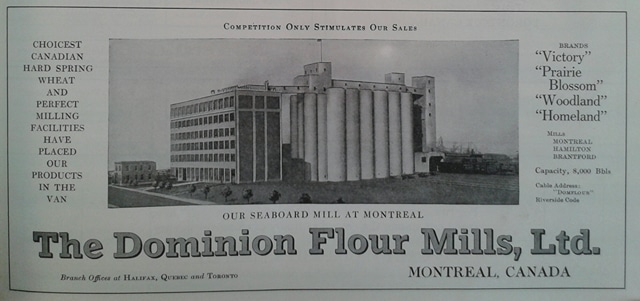

‘The Dominion Flour Mills, Ltd.’, The Northwestern Miller, March 13, 1929, p.1029.

‘The Ogilvie Flour Mill Co., Limited’, The Northwestern Miller, January 22, 1936, p.253.

‘The People’s Mills’, The Canadian Miller (March 1892), p.5.

Brennan, Paul W., ‘Flour Milling’, from The Canadian Encyclopedia, (ed.) by James H. Marsh (Toronto, 1999), pp.870-871.

Goldie Falkner, Theresa, The Goldie Saga 1793-1886. Accessed online from Lake Country Museum and Archive.

Hilborn, Miriam, ‘The New Dundee Flour Mills’, 49th Annual Volume of the Waterloo Historical Society (1962), p.78.

www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/the-war-economy/farming-and-food/

www.weston.ca/PDF/GWL_History_Britains_Biggest_Baker.pdf

Leung, Felicity L., Grist and Flour Mills in Ontario; From Millstones to Rollers, 1780s-1880s (Quebec, 1981).

Pletcher, David M., The Diplomacy of Trade and Investment: American Economic Expansion in the Hemisphere, 1865-1900 (Missouri, 1998).