At the Mill: Storage

‘Coming now to the important question of how best to store wheat to protect it from damage, it will be instructive to review briefly the conditions under which the purchases of wheat are made in large modern mills. Taking as an example the case of a mill producing 1000 sacks of flour per week, the quantity of wheat required, speaking generally, will be about 750 quarters weekly, or say 3,000 quarters a month. But under ordinary conditions the miller cannot purchase wheat in this regular order; at times the wheat he prefers is not on offer at all, – then supplies are rushed in, and he, taking the golden opportunity, buys heavily, some on spot, may be, and some for forward shipment; but, however he may wish the supplies to come, it often happens that several large parcels arrive about the same time, and, as ships wait for no man, the miller must accept delivery. Thus it happens that he is forced to store, say, six or eight week’s supply, and consequently it becomes of great importance to know the conditions essential to safe storage.’ (Voller, pp.75-76)

So before the wheat made it to be milled, it could have spent weeks or months in storage. It was therefore key that millers knew the best way to store grain so Voller, and other authors, became pivotal sources on the correct conditions for storing wheat.

Storage Conditions

For wheat to be safely stored, it was best to keep it in specially designed and built storage units. According to Kick, there were four main conditions these buildings had to fulfil:

- To protect the corn from deterioration.

- To keep out mischievous animals and insects.

- To have ample room.

- To give security against theft and fire. (Kick, p.36)

If this was achieved, then it would ensure that the grain was kept safe and in a good condition to be used in the milling process.

A key aspect in storage, then, was to ensure that the wheat did not deteriorate. This deterioration could manifest itself as mould, sprouting, rotting, insect damage or something else. Different conditions could cause this with the most harmful being an excess of moisture or an excess of dirt. To prevent the build-up of dirt, ‘wheat which on arrival is found to contain dust, seeds, or other impurities to an appreciable extent should, before being put by for a long period in store, pass through a preliminary cleaning plant’ (Voller, p.77). This would prevent the wheat from deteriorating or contaminating wheat already in storage. To prevent a build-up of moisture, the building should be located in a dry area and good ventilation should be installed. Turning the wheat at regular intervals also helps prevent deterioration and the large stores of wheat are kept safe.

When building the storage unit, the other conditions stated by Kick must be taken into consideration. The building should be large to allow large quantities to be stored there, any gaps should be covered with grates to prevent birds and other animals from gaining entry and precautions should be taken against fire. These precautions included the unit being isolated from other buildings, often achieved by installing a wall, and using fireproof materials. This should ensure that the wheat is safely kept.

The new mill and storage facility built for Messrs. Carr & Co. and described in The Miller on 2 November 1885, shows these conditions being taken into consideration:

‘The mill is to be placed on the north side of the new dock lately opened, and parallel to it will be an extensive fireproof grain warehouse… Owing to the nature of the ground it has been found necessary to make a special foundation for the warehouse. This is now being done by Messrs. Walter Scott & Co., the contractors for the dock, who are driving piles to a depth of 35 feet below ground, and filling in the large trenches 15 feet deep with concrete. A special feature of the mill arrangement will be the great silos to be erected at the west end, having a capacity of 89,000 cubic feet; it will be the third of its class erected in England.’ (‘Messrs. Carr & Co.’s New Mill’, p.657)

This warehouse had a special foundation put in ensuring that the grain would not get damp. It was large in size and built with fireproof materials and, although not stated, was presumably animal-proof too. This structure, therefore, should keep the wheat in good condition until it was needed for milling.

Methods of Storing

Whilst the conditions needed to store grain were always the same, the method of storing it could differ. According to Voller, ‘There are practically three methods of storing…in closed bins or silos, in bulks or heaps on floors, and in sacks.’ (Voller, p.79). By far the most popular, and possibly the best, was the method of storing grain in bins or silos. This was a more modern method and allowed the process to become mechanised:

‘The modern silo is more elaborate structure. The framework is of iron, brickwork, or wood, the latter being perhaps most generally used. The bottom is, in some cases, perforated to allow air to enter. Conveyors, elevators, and spouts connect any number of them together, and so allow the contents of one bin to be transferred to some other adjoining; this is occasionally done as a means to keep the wheat in good condition.’ (Voller, p.79).

This meant that the laborious task of turning the wheat could be done by machines. As could the delivery of the wheat into the mill which sped up the milling process and increased efficiency. Once again in the article about ‘Messrs. Carr & Co.’s New Mill’, this process is described:

‘In the silo basement a series of brick-arched passages are arranged underneath the twelve immense grain bins (each 62ft high) to allow the endless worms to receive the grain from the shoots and convey it to the elevator, which in its turn transports it on to the different floors for manufacture.’ (‘Messrs. Carr & Co.’s New Mill’, p.657).

So it was that machinery improved in every aspect of the mill to allow conditions to be controlled and for milling to become more efficient.

Collapse

As with every element of milling, there is an element of danger and the storage of grain is no different. The biggest fear, where storage is concerned, is of a silo collapsing. When a granary was ‘filled with sacks of grain’, very little pressure was ‘placed against the walls or dividing partitions’ as ‘the strains are mostly transmitted through the beams to the columns and so to the foundation’ (Voller, p.80). However, ‘loose grain in deep bulks or silos acts as a wedge, and imposes a direct outward pressure which in badly designed structures eventually may push the walls out’ (Voller, p.81).

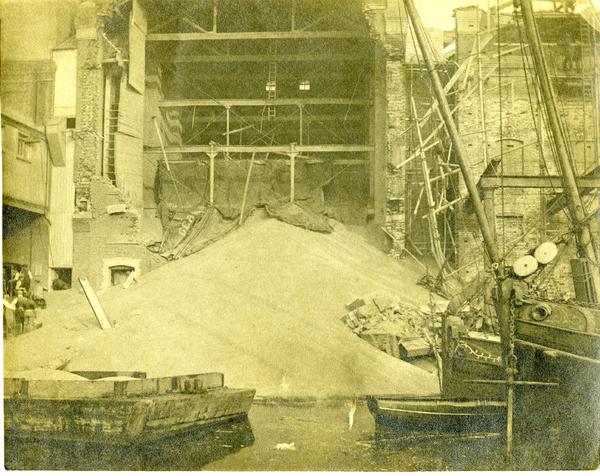

If the wall is pushed out and a collapse takes place, as can be seen in the images of the silo belonging to Cranfield Brothers, Ipswich, it could be a very dangerous and hazardous event. Voller refers to two such events in his work, one collapse in Gloucester had led to the death of a workman and there had been another collapse in Isleworth, but this had no loss of life. Time has not changed the threat of silo collapses as they still take place today and can still cause fatalities. From all over the world there have been reports of silo collapses over the past few years, some containing injuries and fatalities, other not. Many of these collapses took place at farms, rather than mills, but were still involved with the storage of grain, a hazardous occupation.

Therefore, the storage of grain was not as simple as piling wheat up in a corner and using it when you were ready. Instead much thought had to be put into the building and conditions and Henry Simon was correct when he wrote ‘Hardly secondary in importance to the mill buildings themselves are the granaries and warehouses intended to receive the raw material and finished products of the mill’ (Simon, p.27).

Sources:

Kick, Friedrich, Flour Manufacture: A Treatise on Milling Science and Practice (London, 1888).

‘Messrs. Carr & Co.’s New Mill’, The Miller, (Nov 2, 1885), p.657.

Oxley, T. A., The Scientific Principles of Grain Storage (Liverpool, 1948).

Simon, Henry, The Present Position of Roller Flour Milling (Manchester, 1892).