Building a Mill: Workforce

The mill has now been built and filled with the best, new machinery. However, ‘Fine buildings, located on traffic arteries, and equipped with the very latest of mechanical appliances do not, alone, make successful bakeries’, or in this case, mills, ‘It is intelligently trained and loyal man power that determines the success or failure’. This was said by W. E. Long in an address to the Junior National Convention of the American Society of Bakery Engineers, in San Francisco, and recorded in The Northwestern Miller and American Baker. Although this address was directed towards bakers and bakeries, it could easily have been for millers and mills as they too needed ‘intelligently trained and loyal man power’ to succeed.

Training

The first consideration to make in regards to workforce is whether to hire an already experienced workforce or an inexperienced one and train them yourself. In the early days of roller milling this was not a decision as the roller milling process was so new and novel a process that very few men could actually claim to be trained in the roller milling process, its continued progress was ‘so rapid and continuous, it is always difficult to get a staff of men sufficiently skilled’ (Simon, p.5). Therefore, once hired, a workforce frequently had to be trained as the likelihood of hiring an already experienced man was slim. Today there are multiple milling programmes to choose from, such as the milling diploma offered by nabim (National Association of British & Irish Flour Millers) and their partners, Campden BRI and Buhler Training Centre, Switzerland; and the Milling Technology School run by Ocrim in Cremona, to name just two. However, at the beginning of the 20th century when roller milling was still a relatively new phenomenon, these institutions did not exist and owners and workers had to look elsewhere.

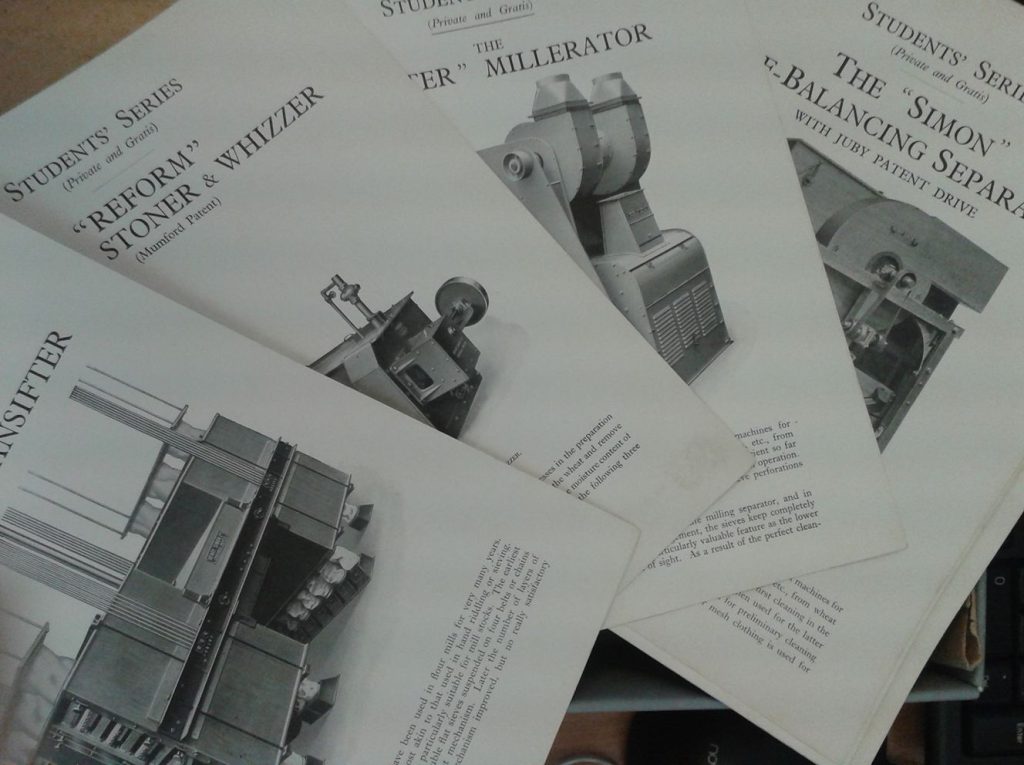

The most popular way to receive an education on roller milling was through the reading of different publications. This included journals such as The Miller, which provided Correspondence Courses, material produced by companies, such as the Simon Students’ Series, and text-books written by a variety of authors, including Friedrich Kick and especially William Voller. As this was just the beginning of the roller milling industry, so too was this just the beginning of educational roller milling publications. The NJIC Technical Education Series was published 1926-1939 and nabim are still producing educational journals today. To learn more about these and other educational publications, click here.

When a miller or worker had an issue regarding a roller mill, these publications could frequently help them. T. R. Over, a miller in Berkshire from 1904 onwards, discovered that his ‘chief obstacle’ in upgrading his mill was his ‘ignorance of Roller Milling’. He sought out an educational publication and ‘After waiting many months for a bookseller to find a technical book on Flour Milling, I secured a copy by Voller! and also a Convention issue of “The Miller”’ (Over, p.1). So what was so special about this work by Voller that caused so much excitement in being able to purchase a copy?

Modern Flour Milling by William Voller was first published in 1889, with many subsequent editions then produced. It was one of the first text-books written about the topic of milling and added to the ‘spread of technical education’ which was ‘aided largely by a powerful and able milling press’ (Voller, Preface). The purpose of the work was to ‘produce a book which shall be of service to practical men whether engaged in business on their own account, or serving in any subordinate capacity’. It contained detailed information about the general process of milling, the more specific roller milling process and the different machinery. Through this work a student could learn what they needed to know and become trained in the world of roller milling. Once one had learnt they could share what they knew with their co-workers, a common practice as seen in Philip Hancock’s memoirs when the Mill Foreman at Westgate Mills, Canterbury, ‘helped me considerably to grasp the principles of roller milling’ (Hancock, p.5).

Workforce Demographic

As trained as a person needed to be to understand the milling process and deal with the complicated machinery, much of the work done in a mill was more physical than technical. Packing flour, and then carrying the sacks to carts and lorries to be taken away, was a common job. Indeed, when Philip Hancock started work at Westgate Mills, Canterbury, ‘at first I helped pack flour, load and unload vans’ (Hancock, p.5). These two watercolours show workers, thought to be from Phoenix Flour Mills, bent over by the weight of the flour sack they are each carrying on their back. It was this physical exertion that led to men being hired and women being overlooked as it was not thought that they could handle the exertion. However, during the first fifty years of the 20th century there were two dramatic events that changed this way of thinking, namely the First and Second World War. With men volunteering or being conscripted into the armed forces, women stood up and filled the gap their fathers, husbands, and brothers left. The photo here comes from the Imperial War Museum and was taken in September 1918 at the Ranks Mill in Birkenhead. Rather than straining, bent double from the weight of carrying a bag of flour on their back, they are using trolleys which would still efficiently complete the job of transporting the flour from the mill to the transport. This job was not necessarily skilled and as this shows, anyone could do it!

Loyalty

Once an employee has been hired and trained, it is cost effective to keep them for as long as possible to avoid having to hire and train new workers. Therefore, the second category, as stated by Long, of men being ‘loyal’ must also be considered and employees needed to be kept happy and made to feel like a valued part of the process. Joseph Rank was a boss who may have thought less about others feelings and making them feel valued given that he was a traditional Victorian. In the biography Burnett wrote about Rank, he is described as ‘apt to make inordinate demands’ and that ‘His methods were dictatorial’ (Burnett, p.192). However, despite this ‘apparent inconsiderateness when exercising autocratic control of his staff’ it was ‘balanced by almost excessive generosity if one of his men broke down under the admittedly severe strain’ (Burnett, p.195). Whilst his behaviour may not have encouraged loyalty at first, his genuine care for each individual when the occasion arose led to ‘their loyalty through all the years of his active life’ which Burnett believed to be ‘his best memorial’ (Burnett, p.226).

Furthermore, the company Joseph Rank Ltd. itself continued to care for their employees after Joseph Rank himself had died. Solent Flour Mills in Southampton had been built in 1934 by Joseph Rank who was determined to build it, despite opposition from many co-directors. However, it was bombed during the Second World War and as result, was rebuilt and re-opened in 1951. As a part of this, in 1949, the architect company, Gelder and Kitchen drew up plans for employee housing. The plans for these buildings, held here at the archive, reveal efficient use of space to make a comfortable dwelling with plenty of amenities: a 3 bedroom house contained a coal box, a sitting room, living room, kitchen, 3 bedrooms and separate W.C. and bathroom. However, as with all structures they had to be given planning permission from the Borough Architect’s Department, which was not always a foregone conclusion. Whilst they may have been given permission to build houses 230/236, Foundry Lane and Kingsley Road, other plans were refused. Nevertheless, the employees still had housing to live in a half an hour walk away from their place of employment, which continued to mill and celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1984 when employees were all presented with medallions as a part of the celebrations.

So loyalty from employees was an important aspect for a successful mill. This loyalty could be fostered, as shown by Joseph Rank, through care of workers when suffering difficulties and the supply of housing for them to stay in. Another company good at fostering loyalty was Cranfield Brothers. The employees there formed many sports teams together, from cricket to football, and this joint venture fostered a group mentality and loyalty to their company. This company made it to their 75th anniversary and at the celebration awarded their employees with clocks to commemorate the occasion.

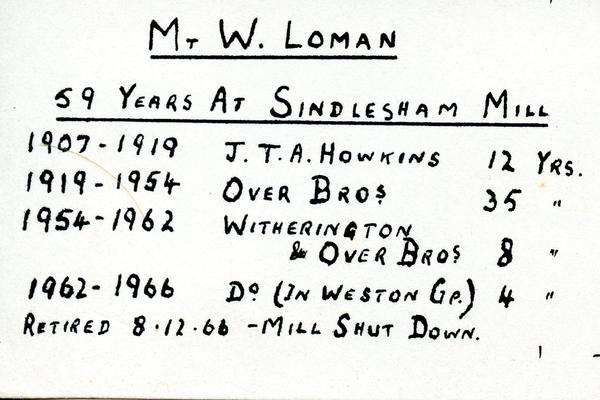

On the other hand, rather than being loyal to an individual or a company, a worker may have been loyal to a mill or his profession. This record of Mr. W. Loman shows him working at Sindlesham Mill for 59 years. During this time he started work for Mr. J. T. A. Howkins, until he sold the mill to the Over Brothers. Mr Loman continued to work for the Over Bros. for 35 years and another 8 years after they had merged to become Witherington & Over Bros. In 1962 the company was taken over by the Weston Group who Mr. Loman worked for until they closed the mill down in 1966 and he was forced to retire. Mr. W. Lowman could not be called anything but loyal but to Sindlesham Mill rather than any specific company or individual so housing, sports teams and help during difficult periods was not the motivation behind his actions, his love of milling was.

So, by hiring men and training them in the profession, loyalty was fostered in them meaning they would be motivated to make the best product possible. With this trained and loyal workforce along with a building built for purpose at a specially chosen location and filled with the best modern machinery, it is time to start milling…

To read about the milling process in our ‘From Field to Shelf’ section, click here.

Sources:

Burnett, R. G., Through the Mill: The Life of Joseph Rank (Oxford, 2004).

Hancock, Philip, ‘Extracts from “Rambling Recollections of a Rural Miller”’ (1980): FULL-22162.

Imperial War Museum photograph of female workers at Ranks mill, Birkenhead, © IWM (Q 28278). http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205213688

Long, W.E., ‘Building Men for the Bakeshop’, The Northwestern Miller and American Baker (Minnesota, February 27, 1929), p.806.

Over, T. R., Fifty Years of Milling: OVER-007.

Simon, Henry, The Present Position of Roller Flour Milling (Manchester, 1892).