Building a Mill: Location

A young, ambitious miller with money to burn at the beginning of the 20th century may find themselves wishing to build a new mill. They may wish this mill to be on the new roller system and rival the big companies like McDougall Brothers, Spillers, and Ranks. For this to be accomplished they would have to consider many factors, purchase new equipment and hire a workforce. However, before doing this, the very first step to be taken, after ensuring you have enough money to fund the project, is to answer one very simple question:

Where is your mill going to be built…?

This was an important question for millers and companies in the 19th and 20th century as there were numerous issues to consider. According to William Voller, respected teacher on mills and flour milling, there were two main considerations in choosing a location for a mill: ‘firstly, access to a good wheat supply; and secondly, a sufficiently large population within the competitive radius of the proposed site to allow of the output being disposed of without excessive freight charges’ (Voller, p.397). So a mill close to the raw product and close to a market for the finished product. This may sound straightforward but in reality meant that many other decisions had to be made.

Wheat Supply

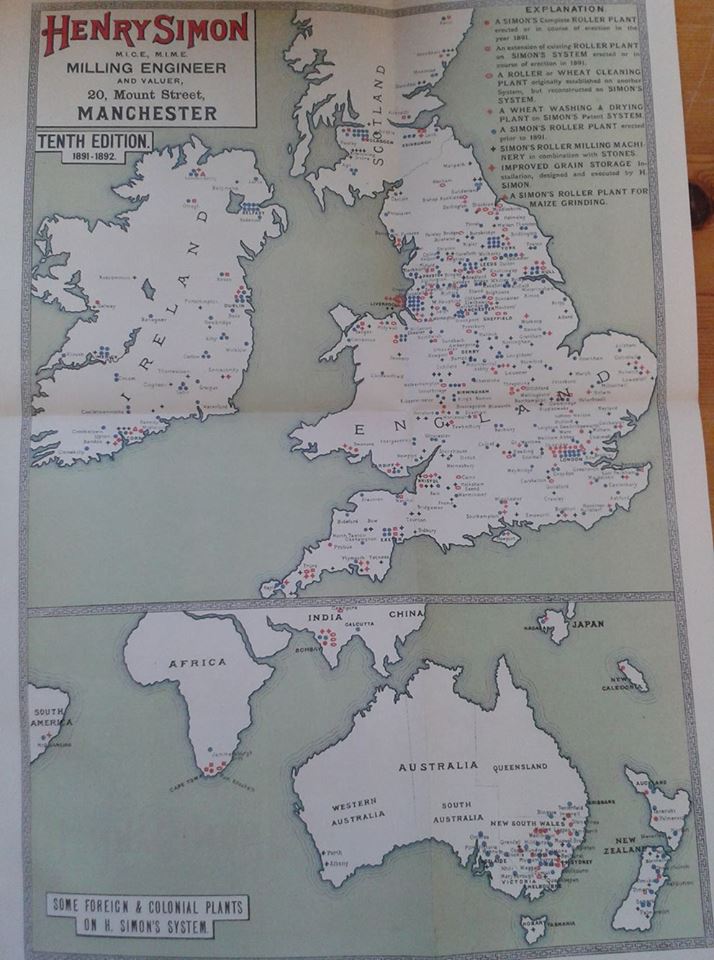

The first decision was: What kind of wheat are you going to mill? The introduction of roller milling had seen a change in the demand of wheat in Britain. Wheat grown in Britain is typically soft and therefore well-suited for traditional stone milling. However, roller mills are better suited to the hard wheats produced in North America, Eastern Europe and Russia. Therefore, on establishing a mill, a decision has to be made between milling hard or soft wheat. If your decision was to mill the softer English wheat, or even a mixture of wheats, then your ‘mill should be of modest proportions and located in any wheat growing district large enough to afford the necessary supply’ (Voller, p.397). Furthermore a combination of rolls and stones may be best suited to your milling needs, a popular choice given the numerous examples displayed on the map produced by Henry Simon. However, if, as many did, you made the change to harder imported wheats, another decision had to be made between grain from America and grain from Eastern Europe. If your intention was to use imported Russian wheat, then a location at a port on the eastern side of the country would be best suited. However, as North America was by far the leading supplier of wheat at the beginning of the 20th century, most millers found themselves at a port on the western side of the country to be where the wheat arrived.

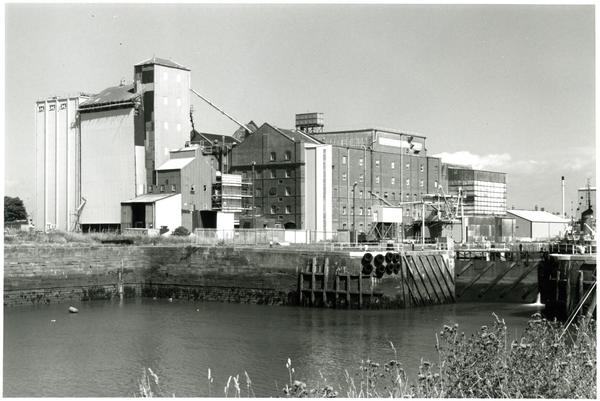

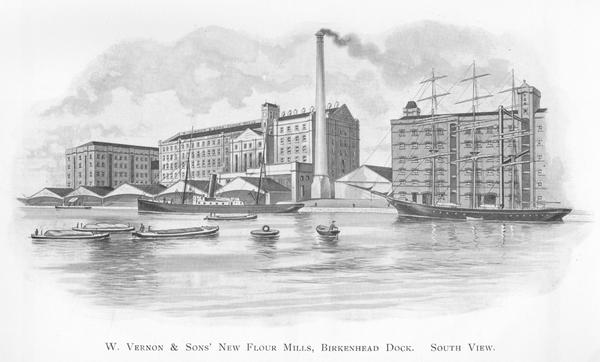

The map of mills fitted with Henry Simon roller machinery in 1891-92, portrays this high proportion of mills at ports, especially in the west. Receiving grain at ports on the western side of the country, were mills in Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, and Glasgow. However, mills were not solely located on the western side of the country with a high concentration of mills in Hull and London too. As these mills clustered at port sites, it could lead to mills from different companies being located next to one another. Birkenhead Docks in Liverpool is a good example of this as in ‘the decades leading up to the First World War, Liverpool become one of the leading flour-milling centres in the world’, meaning many companies were based there (Bielenberg, p.79). Mills could be found at Birkenhead Docks belonging to W. Vernon & Sons’, Spillers, and Ranks. Competition side by side but when the Second World War broke out it did not matter who the mills belonged to, they were bombed indiscriminately as part of the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign with Buchanan’s Flour Mill, belonging to Spillers, completely destroyed.

Whilst mills located on ports were close to the arrival of imported grain, those located in the country could be on the doorstep of the raw product. In Western Australia, many mills established from 1890 to 1930 were in rural locations, and the reason ‘was, quite simple, economic. It made sense to site mills close to the source of supply’ (Lang, p.43). Western Australia was known for its rich supply of wheat so the establishment of the first roller mill in the province 1889 could make sense if there was also a ‘sufficiently large population’ to allow for the output. Despite being a remote province that had been mainly filled with convicts and frontiersmen, the discovery of gold during the latter half of the 19th century led to an influx of people during the gold rush, meaning there was plenty of demand for products produced by the growing number of roller mills. So, despite not having a modern port until Fremantle was completed in 1900, the roller mills in Western Australia survived due to their proximity to the raw product and a demand for the finished product. Whilst the map produced by Henry Simon suggests that they were not responsible for installation of most of the machinery in the province, the machinery was still present and their location meant the mills survived into the 20th century, although numbers did then begin to decline.

Communication Links

Meanwhile, in Britain, mills could not guarantee being able to combine both the raw product and high demand for the finished product on their doorstep. This could be compensated by good communication links. Although not drawn, the Henry Simon map shows a line of mills located on the River Severn with mills in Gloucester, Tewkesbury, and Worcester. This proximity to water transport, or conversely, railways, and main roads was key for these mills, as without it, they were doomed. For mills that were already in existence, this need to be close to transport links could be problematic, but for those building a new mill, it was yet another consideration to take. This can be demonstrated by the Foster family in Cambridge. Located in a university town, the demand for product must have been high but access to the raw product more limited. The Foster family already owned three mills in Cambridge, however, Cambridge University would not let them build railway lines to them. In 1896 the family built a new mill and to solve this transport issue, they built it barely 100m away from the railway station. This access to a transport link allowed the mill to survive throughout the 20th century with Spillers taking it over in 1947 and milling continuing into the 2000s. Their other mills may have faded away but Fosters/Spillers Mill next to the railway line survived.

So, as Voller said, for a mill to be successful a location was needed that was both close to the raw product and to the demand for the finished product. In many cases, but not all, the closest a mill could be to the raw product was at a port or a railway station that was as close as possible to where the grain was coming from. The required good transport links and taking time to consider the most efficient site. However, time spent at this initial stage could save money further down the line so was worthwhile. Once this ideal location that catered to your needs had been chosen, the time then came to consider the building itself…

Sources:

www.cambridge2000.com/cambridge2000/html/0008/P8252198.html

Lang, Ernie, Grist to the Mill: A History of Flour Milling in Western Australia (Perth, 1994).

Simon, Henry, The Present Position of Roller Flour Milling (Manchester, 1892).