External Impacts: Second World War

This Gun

Who is this man,

This man who holds a gun?

His gun is different

Yet, it is the same…

His has a staff of wood,

A blade of steel;

A hoe they call it…

Yet, it is a gun!

His cool nerve can’t

Respond to ship or plane;

He is needed here!

He knows the feel of soil,

The feel of grain.

His rough palms hold

The bounty of the world,

As he shoulders

His hoe…his gun!

Phyllis M. Steele

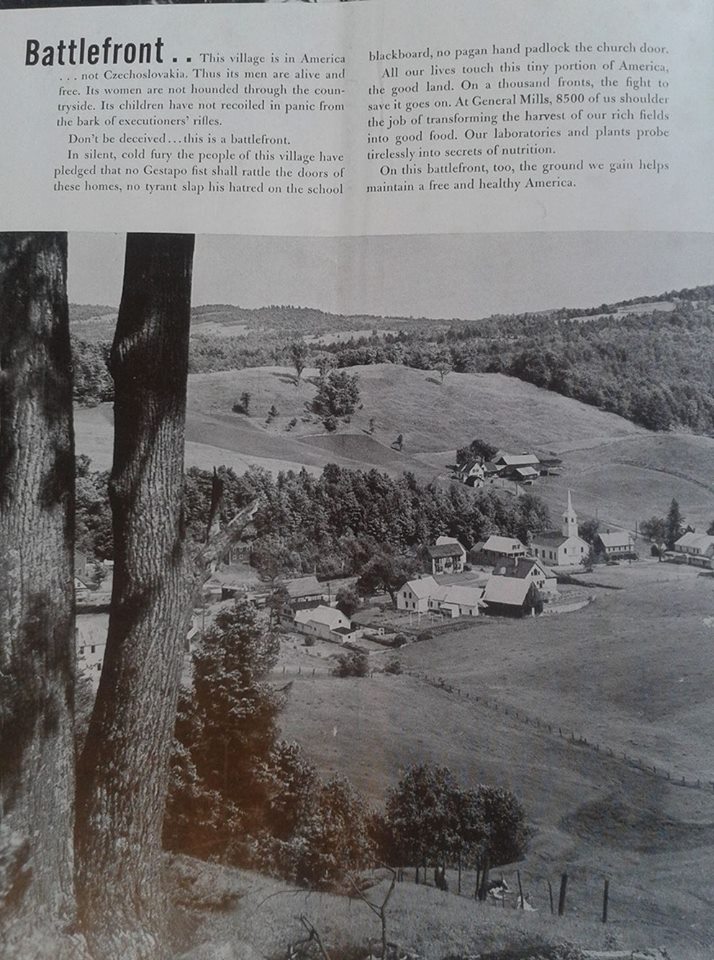

This poem was published in the American journal, The Northwestern Miller on 3 March 1943, just over a year after they had joined the Second World War. With the main fighting taking place far away from American shores, this man was fighting his own battle and wielding his own gun as the battle to produce food and keep everyone fed continued. This battle would be fought by all, all over the world: farmers, millers, and bakers; men, women, and children. It had been fought before in the First World War and would now be fought again.

The first casualty that big company mills faced was the loss of the workforce. Men volunteered and were then conscripted. As a result of this, labour had to be found elsewhere and just like in the First World War, it was frequently women who filled this gap. Editions of The Northwestern Miller from during the war show this as there were numerous articles concerned with the workforce and women: ‘18 Ways to Meet the Labor Shortage Problem’; ‘Wisconsin Bakers Seek Female Work Law Change’; and ‘Training Women Workers’ are just a few examples. The Wisconsin Bakers sought to be allowed to use female workers in the hours between 6pm and 6am to deal with the ‘seriousness of the help problem’; whilst one of Lucius S. Flint’s 18 suggestions was to hire married women. Meanwhile in Britain, many big companies, including Joseph Rank Ltd., hired women and they also took over the running of small family run mills when the male members of the family had left. The hole left by men joining up to fight was therefore not a critical wound as others stepped up to fill the ranks.

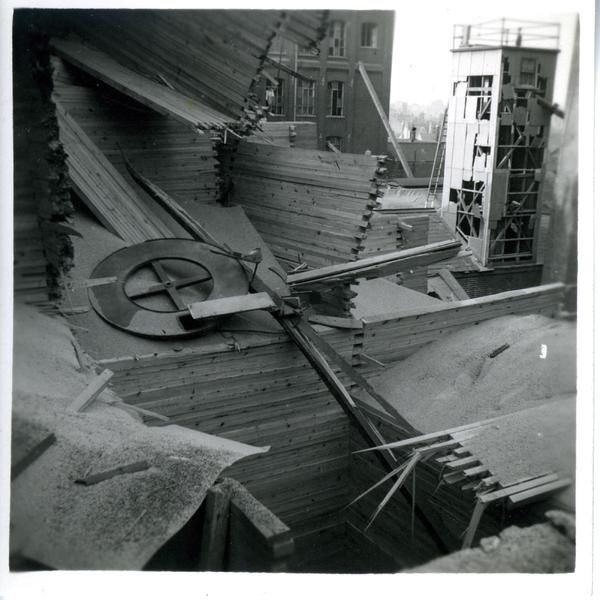

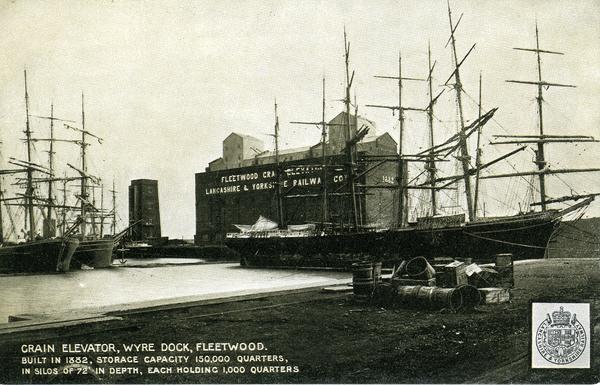

This rejuvenated workforce was dependent upon having somewhere to work, something that was not always guaranteed during the Second World War. Despite aerial attacks from zeppelins and Gotha bombers during the First World War, this was nowhere near the scale of the bombings that would be seen in the Second World War. The German bombing campaign would leave thousands dead, cities in ruins, and many homeless. Most importantly for the milling industry, one seventh of the nation’s flour milling capacity was destroyed. The large company mills had become targets, easily found in the big port towns of Hull, Liverpool, and London, and conveniently clustered together making them an easy target for the Luftwaffe. Hovis Ltd., London; Cranfield’s Flour Mill, Ipswich; Buchanan’s Flour Mills, Birkenhead, Liverpool; and countless others were all casualties of the bombing campaign.

The sight of these grand mills destroyed could be a moving one. These buildings had often been part of the area for many years and their destruction, along with other areas of the city, could be sad. Indeed, Joseph Rank, writing about the destruction of one of his mills wrote ‘It is very upsetting to have parts of your life destroyed in a few minutes’. Joseph Rank had much to be upset about as he suffered more than others due to the large size of his company. In a list of Mills Destroyed or Damaged by ‘Enemy Action’ from 1940-1944 in Milling, 2 June, 1945, three mills belonging to Joseph Rank Ltd. were listed as destroyed (Premier Mills, London; Solent Mills, Southampton; Clarence Mills, Hull), whilst two others were listed as damaged (Birkenhead; Belfast). The only other company to have similar losses was Spillers with two mills destroyed and one damaged. Joseph Rank could therefore be excused for being upset, yet after Clarence Mills was destroyed, he travelled up to Hull to bring comfort to others. After being assured that in the chaotic madness that must have followed the bombing, the horses had been rescued, he was ready to move on stating: ‘What’s done can’t be undone. It’s no good thinking of the past. It’s the future that matters. A few bombs can’t destroy our work. After the war we shall build new and better mills’. Despite probably feeling a deep personal loss, he chose to cheer others by focusing on the future after the war, a future that would see his legacy live on.

As well as the loss of manpower and buildings, millers and consumers also had to sacrifice their independence, and possibly their taste buds. With the difficulty of importing goods, given the situation at sea, the government had to establish strict control. Lessons had been learnt from the First World War when the Wheat Commission, which controlled the import of wheat, had only been established halfway through the war and flour mills had only come under state control in April 1917. With the outbreak of war in 1939 the government took immediate action to ensure the shortages and fears from the First World War were not repeated. The government bought in rationing almost straight away and took control of the mills. However, bread as a staple was not officially rationed until after the war. Indeed, white bread was still obtainable until early 1942 but from then on it was a luxury that was impossible to maintain. Instead, Britain was subjected to the ‘National Wheatmeal Loaf’, bread made from flour of eighty-five per cent extraction. It was generally disliked with Ernest Bevin, a Labour politician, supposedly telling the Deputy Prime Minister ‘that the loaf is indigestible. I can’t digest this stuff in the middle. I throw it away: it’s just waste’. Still, it was a sacrifice the population had to make and there were numerous campaigns to encourage them and help prevent waste.

Elsewhere in the world this bread would have been received with open arms. In the sieged city of Leningrad millers scraped flour dust off the walls to incorporate into bread along with cotton-seed cake and hydrolysed cellulose extracted from pine shavings. In the occupied Netherlands, they suffered a famine in 1944-45, meaning that by April 1945, their bread was rationed to 400 grams a week. Around the world people suffered and starved so Britain’s use of barley and oat flour as substitutes seems a smaller sacrifice than many others had to make.

The war finally ended in 1945, although this did not mean the end of governmental control. Indeed, in Britain bread was rationed from 1946-1948 after the wheat crop had failed. Nevertheless, they could look back and know that everyone had done their bit. They fought in the fields, they fought in the mills, and they fought in the kitchens. The peoples of the world endured, the everyday soldier’s fought their own private battles and the mills played their distinguished and important role in feeding the population of the world.

To read about the personal effect that the war had on two roller milling family dynasties, click here. To read about the history of the Over Family, including the impact of both World Wars on them, click here.

Sources:

‘Flour Mills Destroyed by Enemy Action (1940-1944)’, Milling, 2 June, 1945, p.377.

Burnett, R.G., Through the Mill: The Life of Joseph Rank (London, 2004).

Calder, Angus, The People’s War: Britain 1939-1945 (London, 1969).

Gazeley, Ian; Newell, Andrew, ‘The First World War and working-class food consumption in Britain’, in European Review of Economic History, Vol 17 (2013), pp.71-94.

Reid, Anna, Leningrad: Tragedy of a City Under Siege, 1941-44 (London, 2011).

The Northwestern Miller, 15 November 1942.

The Northwestern Miller, 3 March 1943.

http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/bread-a-slice-of-first-world-war-history/