Manufacturers: Thomas Robinson and Son Ltd.

Thomas Robinson & Son, the prominent mill machine manufacturers did not start with manufacturing milling machinery, nor with Thomas Robinson. Instead, the history of this firm starts with William Robinson, a timber merchant. The first record of his business is from 1813, when it is recorded in a ledger that he purchased oak and cypresses from a neighbouring estate for £159. The next key date for this establishment was 1835 when William Robinson entered into a partnership with his brother, Thomas Robinson. A year later, William Robinson died but his endeavours had clearly been prosperous as he left a fortune of £2000. Thomas Robinson was left as the sole proprietor of a business that had only been founded the previous year.

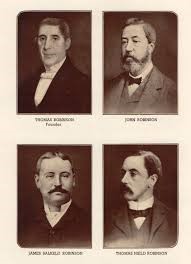

Thomas Robinson looked for a new partner to replace his brother and one was found in his son, conveniently also named Thomas. On 1 January 1838, Thomas Robinson & Son came into being at a location on Drake Street. This partnership only lasted eight years, during which time the premises moved to a larger site on Water Street. In 1846, the younger Thomas Robinson left to join a partnership in Liverpool and his place was taken by his brother, John Robinson, so Thomas Robinson and Son continued.

The forty years after John Robinson joined the family business were good for the firm. Described as the ‘driving force’ behind expansion, he saw the firm move from Water Street to a bigger premises, with a railway connection, on Fishwick Street where ‘a sawmill, foundry and fitting shop’ were all built (Burgess, ‘Part 1’, p.6). This expansion in property led to an expansion in workforce. In 1861, John Robinson recorded in the census that he employed 250 men at his firm; ten years later this number had increased to 600. The censuses which provided these figures are useful for seeing how the business expanded, along with seeing the extent of family involvement in the firm. In 1861 John Robinson was the only Robinson connected to the firm as his father had died two years earlier and his children were too young to join. John Robinson was therefore the sole ‘Turner Maker and Worker of Wood Cutting Machines’ in his family. However, by 1871, three of his sons, James Salkeld, Philip Henry, and Thomas Nield, were all described as ‘in business with his father’ as a new generation was introduced to the business.

The introduction of this third generation to the firm was crucial for the survival of the family business. John Robinson died in 1877 and his son James Salkeld Robinson replaced him, turning Thomas Robinson and Son into a private limited liability company and serving as chairman. Two of his brother’s, Thomas Nield and Charles John, helped him run the company, both being described as an ‘Engineer’ in the 1881 census.

The 1880’s saw the dominance of this third generation but this decade was also witness to another major change in the firm. Up to this point, the business had been focused on woodworking machinery, an area that they had become so dominant in that it was stated: ‘It is not so much the case that Thomas Robinson and Son engaged in the manufacture of woodworking machinery, as that the manufacture of woodworking machinery enlisted the service of Thomas Robinson and Son’ (Burgess, ‘Part 1’, p.7). However, 1882 marked the beginning of a new venture: the production of milling machinery.

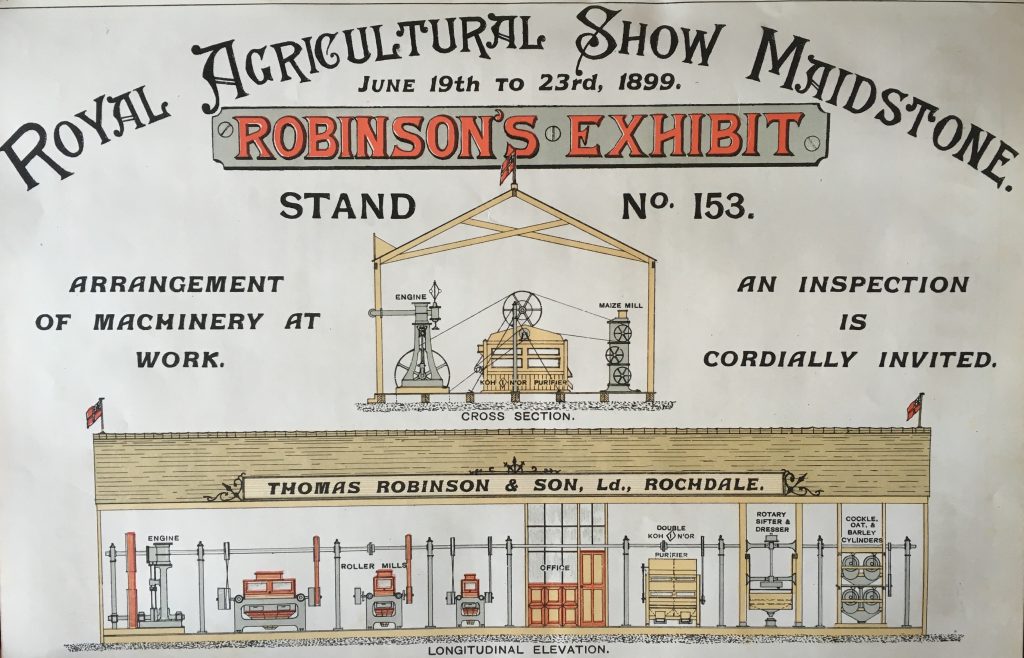

In 1882 a consignment of flour milling machinery arrived in England in a poor and damaged condition. Robinson’s were hired to repair the machinery and, as a later Director explained, ‘Seeing in this new field an ideal opportunity for further expansion, the company took comprehensive steps to enter the market’ (Povey in Jones, p.110). They embraced this new industry with great speed. By 1883 they had started manufacturing their own flour milling machines and the following year claimed that ‘We can fully equip a full roller mill with our own machinery throughout’ (Jones, p.112). At this stage they were mainly being employed by mills of small or medium size but were nevertheless being hired, as in March 1885, they printed a list of 11 recently erected plants. These included plants for the Rochdale District Cooperative Corn Mill Society and the Halifax Flour Mills Society.

The flour milling machinery business was set up as a separate division of the company as it continued its business in wood working too. This division and diversification of the business can be seen through the description of ‘Occupation’ by four of the Robinson brothers in the 1891 census. James Salkeld Robinson, still chairman of the firm, describes himself merely as an ‘Engineer’. However, he was also serving as a Justice of the Peace, County of Lancaster, so may have been less involved with the business than his brothers. He had three brothers working with the company: Thomas Nield Robinson, who described himself as a ‘Steam Engineer and Machinist’; Charles John Robinson, who described himself as an ‘Engineer, woodcutting’, and their youngest brother, Arthur Maurice Robinson, who described himself as a ‘Flour milling machinery maker’. These occupations describe the full array of activities the firm was involved in, all of which were flourishing and helping the business to thrive.

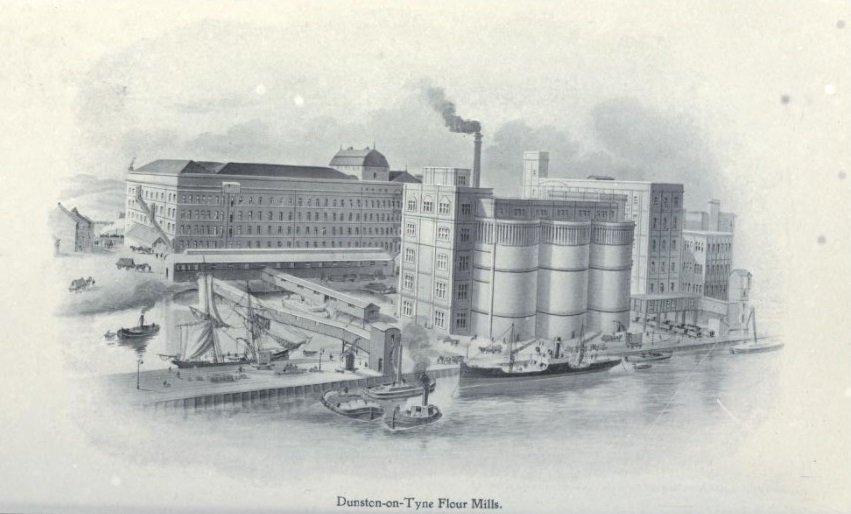

The thriving flour machinery business was reflected through the increasingly more prominent installations Robinson’s were asked to fulfil. In 1891 they installed three plants, each with the capacity of 90 sacks per hour, in the Dunston-on-Tyne Flour Mill built by the Co-operative Wholesale Society. The 1890’s saw them fulfil many other orders until by the beginning of the 20th century, they were so skilled at the installation process that they were able to upgrade a plant for the North Shore Mills in only four weeks. To read more about this mill and this installation, click here.

Despite being based in the north of England, this firm had a worldwide reach. Along with their base in Rochdale, offices were located in London, Paris and Sydney. Indeed, the Australian trade was so profitable that the offices had to move to a larger premises, understandable when in 1903 The Queenslander newspaper reported that ‘there is now scarcely a flour-mill in this State that has not been wholly or partially erected by them’ (‘Messrs. Thomas Robinson’, p.34). This article reported that there was also a good trade in New Zealand with the ‘well-known milling firm, Messrs J. and T. Meek, of Oamura’ deciding to ‘have their plant remodelled on the “Robinson” milling principle’ (‘Messrs. Thomas Robinson’, p.34).

So Thomas Robinson & Son were a successful and well-known manufacturer of flour mill machinery throughout the world by the time the First World War started in 1914. Their manufacturing works were declared a ‘controlled establishment’ in 1915 and they started producing war materials, including ‘hand grenades, bombs up to 112 lb., 8 inch high explosive shells, parts for anti-aircraft guns, control gear for 6 inch guns, mine sinkers, mine firing mechanism and gear cases for the latest invention, “Tanks”’ (Burgess, ‘Part 2’, p.5). Charles John Robinson was chairman of the firm at this time, having succeeded his brother, Thomas Nield, upon his death in 1909. As well as coping with the governmental control of his family business, he had to worry about his son serving overseas. Born in 1899, John Cuthbert Robinson served as a 3rd Class Air Mechanic during the first years of the war until he was discharged in 1917 after receiving his Commission as 2nd Lieutenant with the Royal Flying Corps, three months after his 18th birthday. He only saw action in 1918 but during this year he was captured and taken as a prisoner of war. He returned home after the conclusion war, probably in time for the end of governmental control of his family business in 1919.

The Second World War again saw Thomas Robinson and Son come under governmental control in a repeat of circumstances from the First World War, except this time John Cuthbert Robinson spent the duration of the war serving as chairman for the company rather than as a part of the Royal Flying Corps. The company was responsible for producing munitions but also repairing the milling machinery damaged by the numerous German bombing raids.

At the conclusion of the Second World War, Thomas Robinson & Son looked out on a different world. Mills around the globe were damaged and in desperate need of repair, whilst the firm had lost its last link to the previous generation after Charles John Robinson had died in 1942. The business was now left to the care of the fourth generation and other loyal employees. The firm joined the rush to rebuild and remodel the damaged and old-fashioned mill establishments throughout the world whilst their woodworking demands were also exceptionally high. With this period of peace, the firm went through a modernisation process and introduced new machinery during the 1950’s including ‘the famous MEm Roller mill, PHm Purifier, PSm Plan sifter, as well as new flour high capacity control sieves’ (Burgess, ‘Final Part’, p.6). Thomas Robinson and Son therefore survived the turbulent beginning of the 20th century and by the 1960’s was thriving with 1,050 employees.

Despite their success, Robinson’s had always faced tough competition from other British manufacturing firms. Their main competition had been in the form of Henry Simon Ltd. Both these companies were stalwarts in milling engineer circles and these two grand companies merged in 1988 to become Robinson Milling Systems Ltd. Three years later this firm was acquired by the Satake Corporation forming Satake Robinson UK Ltd., then renamed to Satake UK Ltd. So it was that this manufacturing firm entered a new stage in its long and prosperous career.

Sources:

‘Messrs. Thomas Robinson and Son Limited’, The Queenslander, Dec 26, 1903, p.34.

Burgess, Tony, ‘The Thomas Robinson Story – Part One’, The Grind: The Quarterly Newsletter of the ATMA (NSW Division) Volume 2 Issue 4, (Dec 1997), 4-7.

Burgess, Tony, ‘The Thomas Robinson Story – Part Two’, The Grind: The Quarterly Newsletter of the ATMA (NSW Division) Volume 2 Issue 5, (April 1998), 2-5.

Burgess, Tony, ‘Thomas Robinson Story – Final Part’, The Grind: The Quarterly Newsletter of the ATMA (NSW Division) Volume 2, Issue 6, (June 1998), 4-6.

D. W. Povey, to Rochdale Literary and Scientific Society (1962) in Glyn Jones, The Millers (2001), p.110.

Harris, Nigel S., Wheat flour Milling from Millstones to Rollers (2017).