In recognition of International Women’s Day on 8th March, in this week’s blog we are showing our appreciation for women in milling by featuring two formidable female millers.

Milling: a man’s job in a man’s world, or so it certainly was in the first half of the 20th century. As a profession dating back thousands of years to a time long before women were allowed to vote, much less expected to work, it is hardly surprising that with all its hard physical labour and long hours, milling was a job strictly reserved for men.

That is, apart from a brave few: the resilient and determined women who surpassed social expectations to become millers in their own rights. Rare, but not unheard of, were the hardy female millers who summoned all the physical and mental strength they had, not just to do the difficult jobs of lugging around bags of grain and flour and fixing their mill, but to stand strong against their communities who all-too-frequently viewed them with distaste and suspicion, believing that a woman’s place was in the home – or at least, anywhere but a mill.

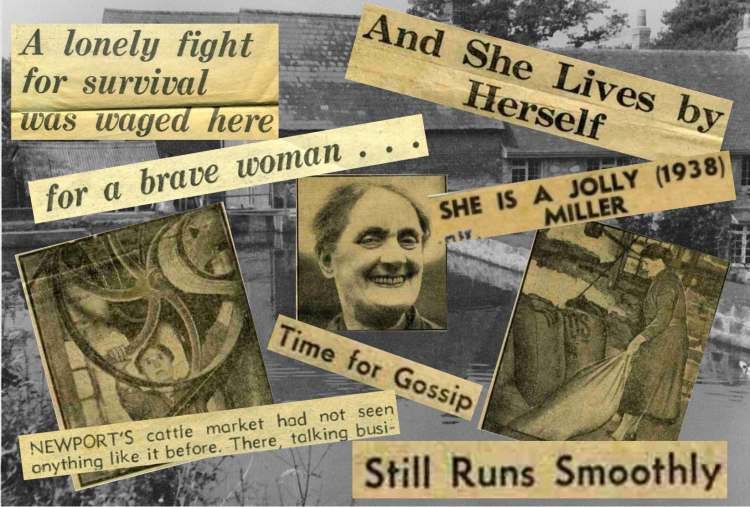

Two of our Gems feature woman millers. In A Lonely Fight for Survival, a newspaper cutting from 1978 tells a tale three quarters of a century old: of Mrs Emma Weeks’ struggle to raise nine children on her own whilst operating Upper Calbourne watermill on the Isle of Wight, following her husband’s death in 1903.

The article describes the difficult situation she was thrown into: without the income from operating the mill and selling flour and grain, she and her family could not survive. But taking on the business herself was regarded with suspicion, if not seriously frowned upon, in the traditional rural community in which she lived. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Mrs Weeks made the only choice she could: to risk being ostracised by the very community which she needed to support her, in the hope that they would buy her produce so that she could afford to feed her family.

Luckily, it seems that all worked out for Mrs Weeks in the end; the article tells that she continued to mill into her old age, shortly before her death in 1943. We can only hope that her career as a miller didn’t make life too difficult and isolating for her in this time.

The second article paints women millers in a rather more positive (although equally uncommon) light. This tells of a certain Mrs Dickinson, who after her husband’s death in 1936, took over the running of his mill in Thunderbridge, West Yorkshire. With no children and only herself and her dog to support, Mrs Dickinson’s life was somewhat easier than Mrs Weeks’. Not only that, but it seems that by the 1930s, women millers were more easily accepted than in Mrs Weeks’ day: the romanticised tone of the article paints Mrs Dickinson as a quirky but likeable old lady, and rather than being suspicious and dismissive of her career, people were merely impressed that such a job could be done by a woman “all alone”.

Indeed, the article focuses on how much Mrs Dickinson loves working in the mill, giving her the name ‘the Jolly Miller’ and quoting her as saying “I always feel happy when I am at work here.” It also implies that she is more than capable of the job: ‘But when Mrs Dickinson’s trained ears hear a pause in the rhythmic rumble of her mill she runs up the steps two at a time with her dog Don, who is her only companion, at her heels’.

Patronising as the article may now sound to contemporary readers from a very different social construct, in its day it would actually have done an important part in reinforcing the fact that women were capable of doing traditionally male jobs: that they could be strong, intelligent and independent. A fantastic video of Mrs Dickinson, from British Pathé, can be viewed on YouTube here.

In the context of their time, these women were extraordinary: before the Second World War, a respectable woman doing physical labour was rare. Before the First World War, it was virtually unheard of. You can tell how unusual women in these roles were even as late as the 1970s, purely from the fact that Mrs Weeks’ story made it to the paper in 1978: a story about a male miller would have been complete non-news.

These stories help us to appreciate the hardships that women of the past went through in order to pave the way for the women of today, who continue to fight for respect and equality in whatever profession they choose to go into. You can read our Gem on Emma Weeks here, and the Gem on Mrs Dickinson here.