Michael Harverson

Michael Harverson (1937-2017) was one of the founding trustees of the Mills Archives. A particular interest of his was the mills of the Middle East, and in his collection we have several accounts of his travels, illustrated with photographs.

| In April-July 1985 he was given a sabbatical from his role as a teacher at Watford Boys’ Grammar School and a grant from the Goldsmiths’ Company, enabling him to spend several months in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, searching for watermills. Some of the information and images which he compiled are given in this newsletter. |

Mills of the Atlas Mountains

| In Morocco, watermills are not yet the few, curious survivors from an almost forgotten and neglected era before the advent of electricity and oil, which they had become in Britain thirty years ago. Here a limited operational revival and widespread restoration have taken place in recent years; there watermills are a commonplace: taken for granted and hardly expected to arouse interest. This lack of glamour seems to have led to few detailed accounts of mill buildings and milling operations in accessible publications. Village women and girls, being mostly illiterate, keep no documentary accounts of their milling; however, they gladly chat about these activities, so long as the interested foreigner has an interpreter or a knowledge of Berber which few have the time and skill to acquire. |

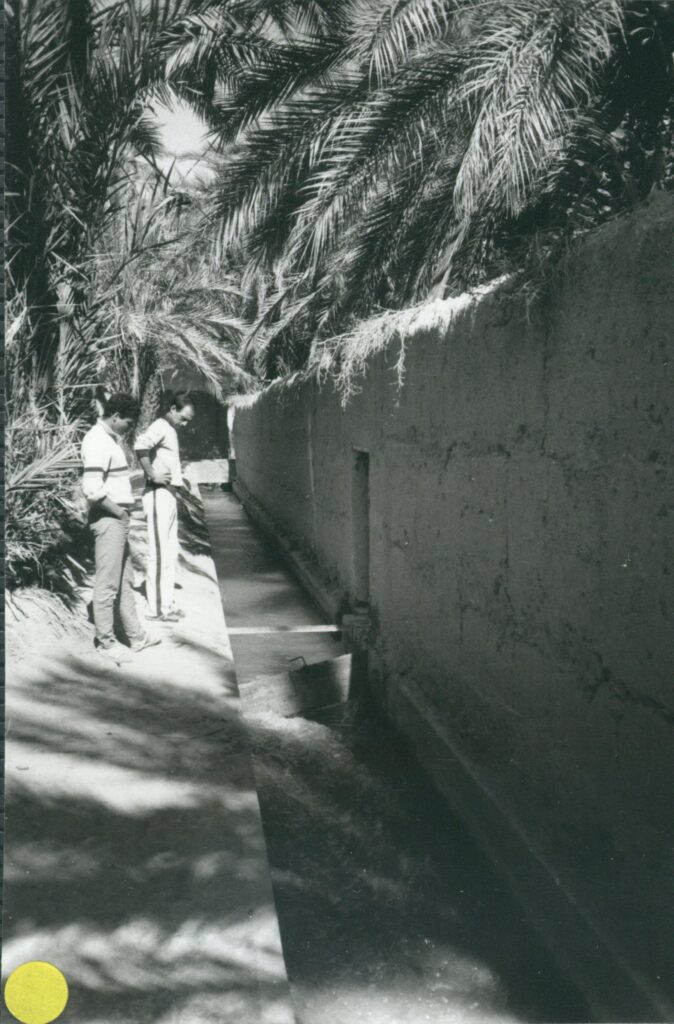

| Water is precious for irrigation in Morocco; except in the north of the country, rainfall is unreliable, even as a winter phenomenon, judging by the first half of the 1980s. The snow that falls in the Atlas Mountains emerges in the springs that feed the torrents in the spring and early summer. The winter of 1984/85 was a distinct improvement on the dry record of the previous 4 years. At Zagora, well south of the mountains, the Dra was unusually full of water on May 1st, thanks to heavy rain for 24 hours. Hope had returned for the parched date-palms in this and similar oases. Everybody was delighted: it was the immediate topic of conversation for a week and the children were splashing in the huge pools with gleeful abandon, much like their counterparts in Southern England after a rare heavy snowfall. This same precipitation had covered the mountain tops with a good fresh covering of snow, sufficient to ensure adequate irrigation water until midsummer. Streams are diverted into the ditches (séguia) that snake their way along the higher side of a village’s terraced fields. Those possessing water rights receive a good soaking every twelve or fourteen days. Once, arriving at a mountain village at 7p.m. I had no sooner been offered shelter by a Berber farmer than he had to tell me to sit at a field’s edge while he busied himself in his green wheat, seeing that the water which was his due for twelve hours from that same moment reached every corner of the long terrace. (I could not of course enter his house since only the womenfolk were at home.) |

So, it is a common experience to thread one’s way through the boulders of a dry mountain stream bed, while not many metres away up the hillside there are six inches of fast flowing water hurrying along to someone’s fields. Many villages have a larger header pond: once filled, its contents are emptied for a certain farmer’s benefit, then it refills over the following hours and the next farmer takes his turn.

An irrigation ditch or séguia at Goulmima on the southern side of the main Atlas range. A sluice board can be inserted to divert much of the water into a leat behind the garden wall

| Both these patterns of water distribution are taken advantage of for watermilling. Since a mill uses but does not consume water, those with irrigation rights have no quarrel with their water passing through a watermill on its way to their fields. |

Each mill can only be worked intermittently of course, especially in early summer. By July many of them are temporarily mothballed: the tailrace arch is walled up, the hopper removed, and the headrace, such as it is in high summer, is diverted. But earlier in the year these small mills, astride an irrigation ditch in the fields or sited close to the outfall from the village pond, work for as many hours as water is flowing in their direction.

Tailrace of a mill in the Ayt Bou Guemmez valley

| On the whole grinding is slow: a kilo of barley took an hour to be ground in one mill where the water was nearing the bottom of the storage pond. The womenfolk, whose lot it is to grind the corn for their bread, couscous and soup, adjust their routine to take account of each day’s priorities so far as the outflow from the pond is concerned. They grind for a very few day’s needs at a time; each mill serves only a handful of families and, if a small queue forms, one is chatting to one’s neighbours in the shade of the walnut trees which seem to flourish beside Atlas watermills: a restful contrast to the hard work of harvest or weeding or household chores like fetching fodder, fuel and water. Incidentally, a more usual figure quoted for grinding barley was about seven kilos per hour; a typical family will consume about thirty kilos of flour per week. |

several hours’ rest

| At places where the millrace is fed by a perennial river: Fez, Chechaouen and Ouzoud were three I visited, milling is organised on a basis more familiar to us in Western Europe. There is a full-time miller, a man, who supervises the customers’ grinding of their grain or does it for them, and who takes a toll (10% of the grain) for the mill proprietor who employs him. At Ouzoud where ten small mills are sited on the very brink of the largest waterfall in Morocco, operating 24 hours out of 24 if custom requires it, the tempo of work was brisk, and they reckoned to grind a minimum of fifteen kilos of barley per hour. Wheat and maize take longer. The best sited mill here quoted 30 kilos of maize, 60 of barley, per hour. |

| Milling for profit is an accepted occupation around the world. |

Owning and running a mill largely for the benefit of one’s neighbours seems like charity on a grand scale in communities that make their scanty-stranded ends meet only with difficulty. Yet, charging a toll is the exception in Atlas mills, though the owner may well expect assistance when a new runner stone becomes essential, when waterwheel blades need replacing or when a minor catastrophe – winter floodwater, for example, suddenly wrecks the single wood and stone structure. ‘God sends the water. Who am I to charge for its use?’ was the habitual reply to my query re tolls. Derelict watermills and a transference of custom to diesel-powered mills, where payment is expected, are certainly features of many villages, but free grinding is generally still available a few miles away.

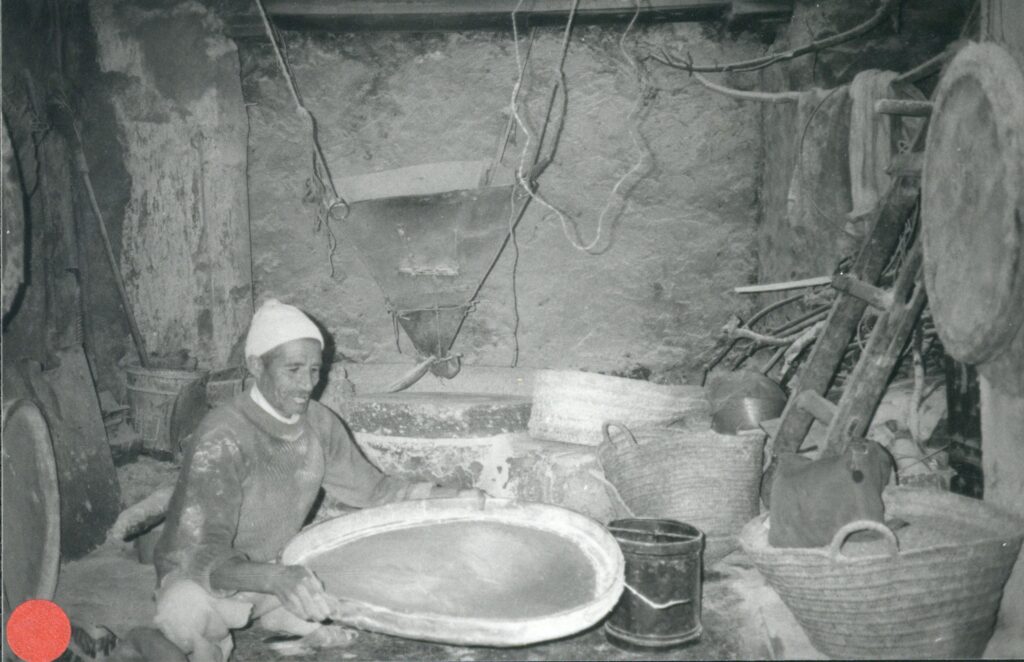

A miller at Ouzoud, with his toll-kettle beside him, contemplating one major finding of my travels: that most mills in the Atlas Mountains charge no tolls!

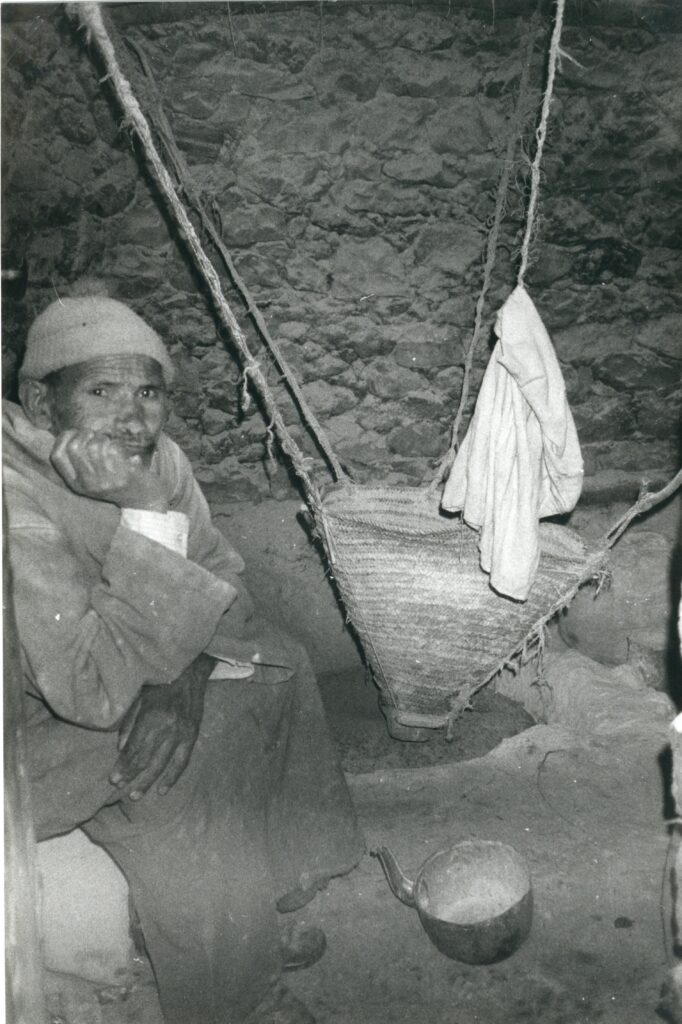

| A watermill is viewed by many small landowners as part of their farming equipment, contributing to the sustenance of the life of their extended family, much as the plough, draught animals and beasts of burden do. In one village the man who had built the fine new mill in 1984 also owned an olive-mill and a balcony full of beehives. The key of his mill was available to those who wanted to use it. He has done most of the work of building and fitting out the mill himself, even making the bedstone and the waterwheel, at the seemingly very modest total cost of 1500 dirhams (c. £150), two fifths of which had had to be spent on buying a runner stone. Another mill-owner who not only farmed his land, but also kept a clock, watch and radio repair shop at the local twice weekly market, and who had more than a veneer of westernisation in attitudes and possessions, responded immediately and positively when asked what he would do if his mill was badly damaged: ‘Surely you would not spend good money on repairs, but would patronise the diesel mill in a neighbouring village?’ – ‘No! I wouldn’t think twice about it: I would have my mill repaired!’ So the omens are good in the Atlas for those who enjoy watermills as examples of simple rural technology and for the majority of village women, inured to full days of hard work in any case, who set store by the facility of grinding the grain for their domestic needs, more or less when they want to, at a mill a few minutes walk from home, and in the form of the cool, sweet-smelling flour which is prized by breadmaker and consumer alike. |

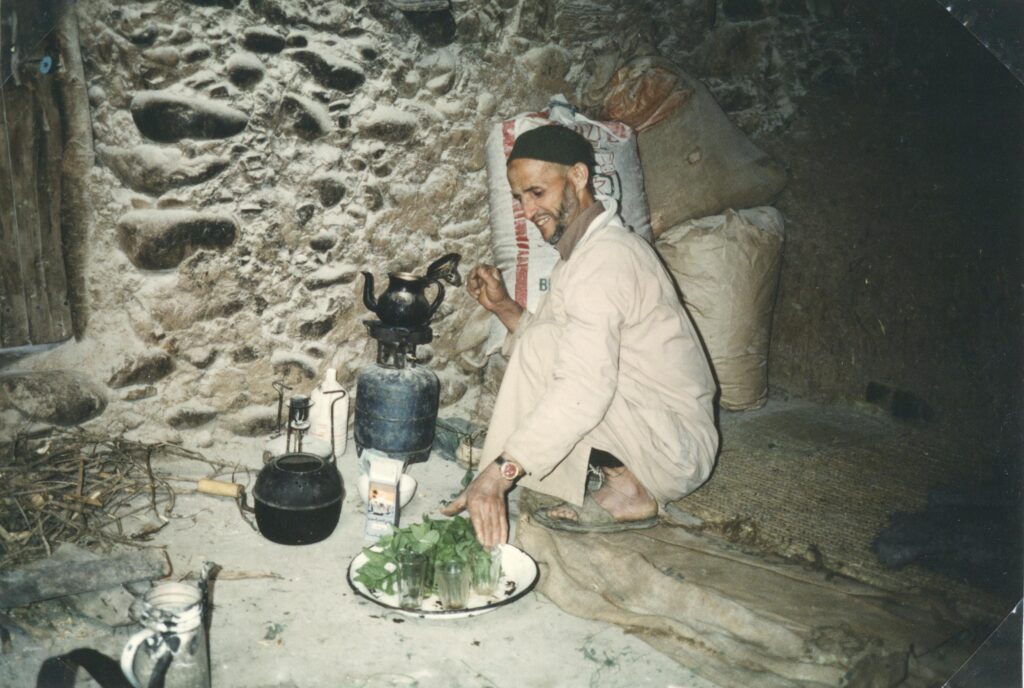

After 8 hours backpacking in June in southern Morocco, tea was welcome!