Cotton mills: Calico

Mildred Cookson

Summary

Calico has been used in Britain since 1505. It is a plain-woven unbleached textile made from cotton. The processing of the cotton stops before the final stage to provide a fabric that is less fine than muslin and less coarse and thick than canvas or denim. With its unfinished and un-dyed appearance it is cheaper than fully processed cotton-based fabrics. Calico comes from the word Calicut, which was a European name for the city of Kozhikode, in Kerela (southwestern India).

Details

The fabric originated from Kozhikode in south-western India and was processed there by the traditional weavers called ‘caliyans’. The raw fabric was then dyed and printed in bright colours. As far back as the 12th century calico was mentioned and described as a ‘printed fabric with Lotus pattern’. The city of Calicut became renowned for producing this sought-after cloth, used by designers, merchants and buyers around the world. Weavers created calico using Surat cotton which made the textile cheap and durable.

The fabric is far less fine than muslin, but less coarse and thick as canvas or denim. Plain-woven from natural cotton fibres, flecks of cotton seeds are often visible in the fabric. It tends to have a cream or greyish tinged finish, making it ideal for dying or printing on. It is a plain-woven textile found everywhere, often used as a neutral base for artist’s canvases, fashion designers mock up dresses, curtains, bed linen and bags.

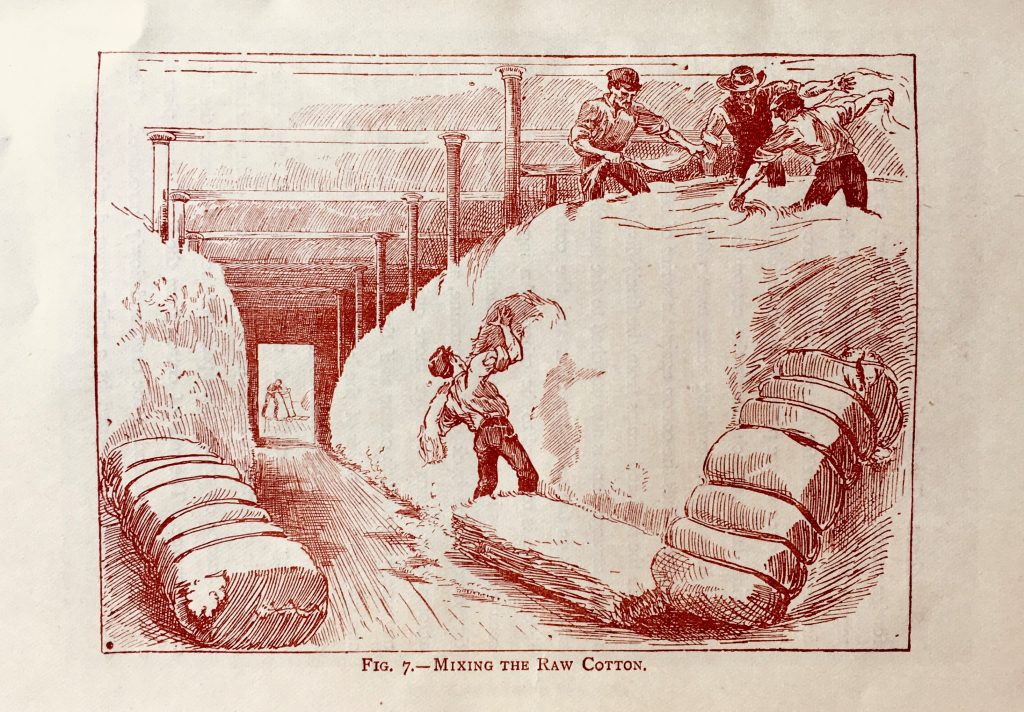

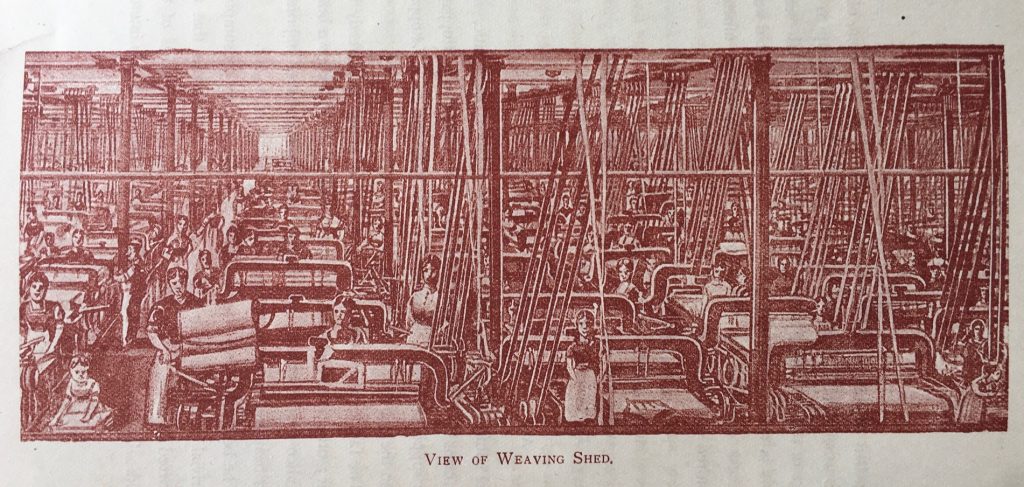

In the 18th century the raw cotton arrived in bales at the UK port of Liverpool. From there the bales were taken to the cotton mills where they were opened and the jute covers removed before they were piled in a high stack for mixing. In this mixing process the cotton was blended to give the desired colour, strength and quality in the thread. After this the cotton passed through a group of cleaning machines. After this the fibres were pulled into alignment and the rest of impurities removed. The fibres were then smoothed out and spun to strengthen them before the weaving process. Calico is created using a plain weave that sees the lengthwise yarns (the weft) passing over and under the crosswise yarns (warp) alternating in each row.

In 1818 the firm of Rylands and Son in Manchester undertook the hand weaving of coloured, coarse linen and calico goods for the Chester trade. John Rylands captured the trade of North Wales due to the high quality of his wares. In 1830 John and his sons acquired their own cotton spinning mill. Linen then became the luxury textile whilst cotton became the staple fabric of the new calico millennium which was about to dawn. John Rylands expanded his empire and at his cotton mill in Gorton, provided jobs for women and girls whereas the men worked in the railway workshops.

Calico as a symbol

Calico Cats, often seen as a good luck charm are domestic cats with a coat that is typically 25 to 75% white with large orange and black patches. Calico refers only to the colour pattern and is not a cat breed. The unusual coloring occurs across in many breeds. Virtually all calico cats are female.

A calico cat must be a tri-color (with three colors in distinct patches, not mixed as in a tortoiseshell cat). Because of its colouring Maryland, USA designated calico as the official state cat in 2001. Its colors of orange and black are shared with the state’s designated bird and insect as they also appear on the state flag.

How Calico is Made (1894)

A small, but beautifully illustrated booklet dated 1894 titled: ‘How Calico is Made’. It was written by CP Brooks for the cotton manufacturing company of Messrs Horrockses, Miller, and Co, Preston, as a guide to the different stages of its cotton manufacture. The 32 page booklet is illustrated with drawings of the various processes. The front cover is particularly special, having a colour engraving of the inside of a shop with the shopkeeper showing a lady his wares. The engraving is dated 1791. The back cover shows a B&W engraving of the company’s works.

50 Years of Calico Printing: the story of Calico Printing Association (1949)

The Calico Printing Association was founded in 1899 and this book marking its 50th anniversary weaves its way through the complex history of calico import restrictions designed to protect the domestic textile trade. It also addressed the need for consolidation in the mid-20th century as more and more cotton mills were rendered uneconomic due to foreign imports

The finished product, calico, proved to be a popular fabric for printing as the process also made the colour designs on the fabric permanent. The prints were originally done with wooden blocks dipped in various colours. This became too popular at the time and as the British Parliament began to see a decline in domestic textile sales and an increase in imported textiles from China and India, decided something had to be done.

The result was The Calico Act (1700 – 1721) which was to ban the import of most cotton textiles into England followed by the restriction of the sale of cotton textiles. This was as a form of economic protection, largely because India at this time dominated the world in this area, also as England had the East India Company it saw the importation as a threat to the domestic textile business.

As the act did not punish anyone for continuing to sell cotton cloth this in turn made smuggling commonplace. It appears that Switzerland and the Channel Islands were top of the list as the two main bases for entrepreneurs for smuggling textiles into France.

By 1714 there were twelve print works in Surrey, Essex and Kent, this prompted an outcry by the silk and woolen manufacturers who called the printed calico ‘an evil to the community’ and said it took away work from the poor. By 1720 the wearing of printed calico was entirely prohibited. This caused many printers to close down until 1736 when the prohibition was lifted, and then with a levy of 6d being put on each yard of the material.

The exemption of raw cotton from prohibition encouraged its import and it became the basis of a new domestic industry, triggering the development of mechanised spinning and weaving technologies, to process the material. This new technology was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded. By the beginning of the 1770s seven thousand bales of cotton were imported annually, and pressure was put on Parliament, by the new mill owners, to remove the prohibition on the production and sale of pure cotton cloth. The acts were repealed in 1774, triggering a wave of investment in mill based cotton spinning and production, doubling the demand for raw cotton within a couple of years, and doubling it again every decade, till the 1840s.

In 1785 at the works of Livesey Hargreaves near Preston, a Scotsman named Bell, invented a roller printing machine. Engraved copper rollers took the place of wooden blocks and instead of the cloth remaining stationary on a long table the cloth now passed under tension between a central drum and the printing rollers which turned it. Each roller was fitted with colour by a brush that rotated in a colour box. The result was that the equivalent of a day’s work for a hundred block printers could now be done in a few minutes by one of these machines.

The first shipment of Lancashire calico from Liverpool to India in 1814 set in motion industrialisation in Asia with the cotton industry playing a prominent role. Two centuries later, calico continues to be produced, but is mainly now imported from India.

Links

Futher Reading:

- 50 Years of Calico Printing: story of Calico Printing Association (1949)

- Burscough, Margaret, The Horrockses, Cotton Kings of Preston (2004)

- Rose, Mary E, The Lancashire Cotton Industry, A history since 1700 (Lancashire Country books, 1996)

- Farnie D A, John Rylands of Manchester (1993)

- Kawakatsu, Heita & A J H Latham (eds), Asia Pacific Dynamism 1550-2000 (Routledge, 2004)

- Mills, Betty J, Calico Chronicle: Texas Women and Their Fashions, 1830-1910 (Texas Tech University Press, 1985)

Images and documents in the archive catalogue

From elsewhere on the web: