Fulling mills

Mildred Cookson

Summary

Fulling is a step in woollen cloth making which involves the cleansing of cloth (particularly wool) to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and to make it thicker. In a watermill the cloth was beaten with wooden hammers, known as fulling stocks or fulling hammers. Fulling stocks were of two kinds, falling stocks (operating vertically) that were used only for scouring, and driving or hanging stocks. In both cases the machinery was operated by cams on the waterwheel shaft or on a tappet wheel, which lifted the hammer.

Details

Fulling is part of the process in woollen cloth making which cleanses the cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and making it thicker. It is also known as tucking or walking (Scots waukin, hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English).

The Romans practised fulling techniques, and probably first introduced the process to Britain. Up to the 12th century the process would have been a manual one involving people physically trampling the cloth in tubs and then in streams. It was the first part of the cloth-making process to become mechanised, and records dating to 1185 indicate a fulling mill at Temple Newsham, West Yorkshire and another at Barton on Windrush, near Temple Guiting in Gloucestershire. Both these mills were set up by the Knights Templar.

These fulling mills processed the cloth made from wool produced on the monastic estates, but the lord of a manor, perceiving an additional source of revenue, sought to derive an income from tolls levied on non-monastic cloth.

After a piece of woollen cloth has been first woven, the fibres of its fabric are loose, airy and unmeshed, and similar in texture and appearance to a piece of cheesecloth or sackcloth, and the cloth at this point still retains a significant amount of oil or grease, introduced during the weaving process. Since oils and grease will inhibit the binding action of dyes, these need removing.

The Fulling process closes together the threads of newly woven woollen fabric with the assistance of soap or acid liquor, to produce a grease free cloth of the correct thickness for future use, including dying.

Knowing the amount of fulling required for a particular cloth was part of the skill of the fuller. It depended on the type of wool, the type of water, the cloth texture, the temperature of the water and the time allowed under the fulling stocks.

Usually the cloth underwent three stages of pounding with beaters. The first stage used a fulling trough containing urine. The second fulling was with fuller’s earth and the third with hot soapy water. Each pounding lasted two hours, with a final thorough rinsing in clean water.

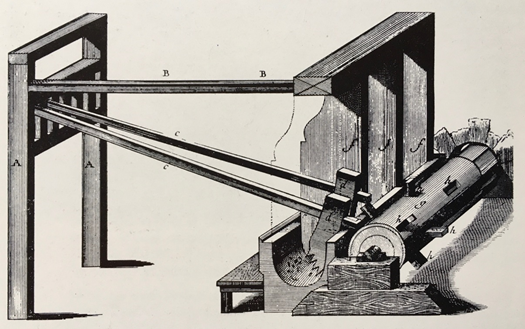

With the advent of the water-powered fulling mill, this name transferred to the whole mechanism itself. The large wooden mallets consisted of a wooden shank with a heavy wooden foot or stock on the end and lifted by means of a cam or trip. These cams were set on a large horizontal shaft and pushed back the heavy wooden mallets or stocks. In larger mills, a long camshaft that raised them in a staggered sequence would operate a series of these stocks.

More usually, fulling stocks were set in pairs, each working alternately and swinging like a pendulum down onto the cloth. The face of the stock had a stepped rather than a flat end, whilst the box which contained the cloth had a curved backboard. These two features allowed the stock to turn the cloth round gradually after each blow ensuring an even application of the fulling process to the cloth, and preventing any excessive wear to any one area.

Links

Pelham, R A, Fulling Mills (SPAB, 1958)

Scott, E K, “Early Cloth Fulling and its Machinery” (Trans. Newcomen Soc., 12, 1931, pp. 30–52)

Parkinson, A J, “Fulling mills in Merioneth” (J. Merioneth Hist. & Rec. Soc., 9(4), 1984, pp. 420–456)

Images and documents in the archive catalogue

List of fulling mills in our database

From elsewhere on the web: The Fulling Mills of the Isle of Wight – Isle of Wight History Centre