Widows

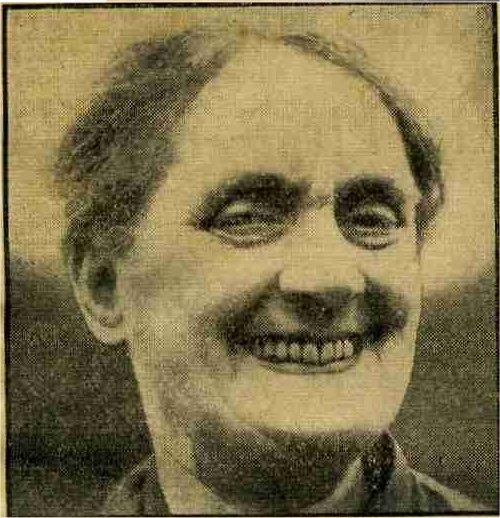

As discussed, women who were already married to a miller or a descendant of a milling family often became more directly involved in the milling industry, trade or profession when they became widowed. Mrs H. Dickinson, the “Jolly Miller” of the photo, is another example of a widow who continued her husband’s business alone. She features in a splendid short film from 1938 on the British Pathe website

In many cases, a widow who became head of her milling household was assisted by other family members who were living in the household. Mary Bromfield, for example, is listed on the 1881 census as a widow aged seventy and the head of Cotleigh Mills, in Upottery, Devon. Her occupation is listed as being a “Miller and farmer of 12 acres, employing 1 man and 1 boy”. Living with her at this time was her unmarried 49 year old son, who was a corn miller. Mary also employed William Mellvish, aged 27, as a “Miller’s assistant”. Further research has revealed that Mary’s husband, William, a miller and millwright, died in May 1865, leaving his widow “effects under £200”.

Examples of similar cases at the time are numerous. Caroline Clarke of Piddle Hinton village corn mill in Dorset and Ann Chown of The Mill at Higham Ferrers, Northampton, also found themselves in 1881 widowed and the head of their milling households. They were both living with male relatives, who were assisting them in the milling profession.

Hannah Newton (née Potter), took over the ownership of Weston Mill in Welford, Berkshire, after her milling husband John Newton (born in Weston in 1773) died in 1822. Hannah went on to mill at Weston from 1822 to 1868, as research by John Bowley reveals. Hannah never remarried after losing her husband John: their last child (Hannah) was actually born shortly after John’s death. Besides the mill, an 1837 tythe map of Welford reveals that Hannah had also inherited part ownership of several of the meadows and two cottages near Weston Mill. Hannah had become a Methodist; perhaps her faith gave her the resilience and heartiness to continue milling at Weston for so many years after the loss of her husband.

Due to a lack of male heirs (Hannah and her husband John had six daughters), Weston Mill was taken over by William Dance (Hannah’s son-in-law as the husband of their youngest daughter Hannah) in 1868. William Dance appears in an 1868 trade directory as the miller at Weston. The Dance family were also millers, in the Marlborough area of Wiltshire. When Hannah Newton died in 1875, over one and a half centuries of the Newton family’s ownership and occupation of Weston Mill came to an end [1].

Update (April 2017): John Bowley has provided a more extensive life of Hannah Newton. You can read it here

Occasionally, widowed lady millers were not as fortunate and found themselves living alone without any members of their family, although this was far more unusual. In these cases, it was common for the widow to have employed a man or boy to assist them in the running of the mill, or to run the mill for them. Elizabeth Benwell of “In the village stream flour mill”, Little Milton, Oxfordshire, is listed on the 1881 census as a widow and a “Master corn miller”, who employed one man to assist her.

Some of the widows who became millers, inheriting the running and business of the mill, also continued in the related trades their husbands had been involved in. Sarah A. Glasscock, of Harlow, Essex, was a corn merchants miller, living with her nephew who was the corn mill manager. Mary Tannar, living at The Mill House, High Roothing, Essex, became a miller and beer house keeper. Ann Chown of The Mill at Higham Ferrers, Northampton, became a miller and farmer of 36 acres. Charlotte Buswell, of Clipston, Northampton, was a miller and baker, as was her unmarried son who was living with her. Mary Bowyer of Stoke Mill in Surrey was listed as the corn mill proprietor, whilst her two unmarried sons in their twenties were living with her and listed as the millers. Hannah Osctoby of Dunnington Common, York, was a miller and innkeeper.

Whitmore and Binyon: engineers and millwrights of Wickham Market, Suffolk, by Phyllis Cockburn, discusses the experience of Elizabeth Whitmore, who was widowed when her husband Nathaniel Whitmore died in 1812 [2]. Elizabeth continued Nathaniel’s millwrights business in Wickham, in the greatest capacity that she could, for example employing skilled millwrights when necessity dictated it. Elizabeth was also a more general merchant and ran a shop. It is quite possible that Elizabeth’s family supported her taking on of a more direct role in the milling industry in Wickham once she had become a widow. Her maiden name was Minter, who Phyllis Cockburn highlights were a prominent and fairly wealthy local family, who may well have supported Elizabeth through this difficult time. John Whitmore, the son of Elizabeth and Nathaniel, went on to found a well known firm of millwrights in the nineteenth century, at first known as Whitmore and Sons and later as Whitmore and Binyon.

Besides women becoming millers as they were widowed, there are also many revealing examples of unmarried women being listed as millers and the head of their households on the 1881 census. Presumably, these women were either born into established milling families, or had the finance, knowledge and opportunity to buy and run their mills outright. Anne Elizabeth Chaffe, for example, is listed as being the head of the household and a corn miller at Shilston Mill, in Modbury, Devon, in 1881, when she was aged just 18. She is also living with a Sampson R. Chaffe, assumed to be her younger brother. In a case such as this, where such a young woman is listed as the head of a milling household, it is likely that Anne had been born into a milling family and had largely taken on the workings of Shilston Mill in order to assist in the family business. Another interesting example is the case of the Irrvin sisters, who were living in 1881 at Sunnyside Cottage, in Kirklinton Middle, Cumberland. Both the sisters, Fanny aged 52 (who is listed as the head of the household) and Jane aged 48, were unmarried and listed as corn millers.

In addition to these case studies, there are many other examples that can be found to support the view that in some instances at least, women had the opportunity, or the obligation, to take on a direct role in the milling industry.

Some examples, though interesting and revealing about the role of women in the milling industry, are exceptional and perhaps not representative of the more general or standard role of women in the milling industry. A Gazetteer of the water, wind and tide mills of Hampshire by C.M. Ellis (proceeding for the year 1968), included a reference to Bere Mill on the River Test, at Whitchurch [3]. At Bere Mill there is a plaque on the wall of the mill house, which states ‘This House and Mill Built by Jane, the widow of Tho Deane Esq, in year 1710’. It is likely in this case Jane Deane was of a particularly wealthy family.

Footnotes

- [1] John Bowley research notes – Newtons at Weston Mill, Welford, Berks, and Wandsworth Mill, Surrey

- [2] Cockburn, Phyllis, Whitmore and Binyon: engineers and millwrights of Wickham Market, Suffolk (Phyllis Cockburn, 2005), p.4

- [3] Ellis, C. M., A Gazetteer of the water, wind and tide mills of Hampshire (proceedings for the year 1968)