Starlina Rose

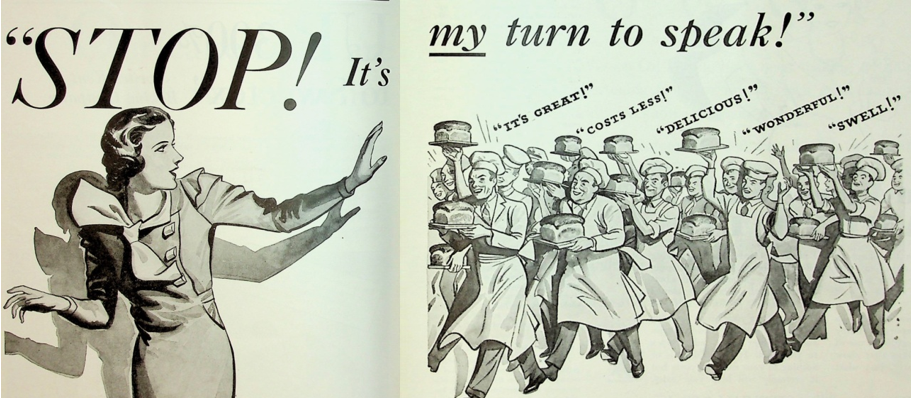

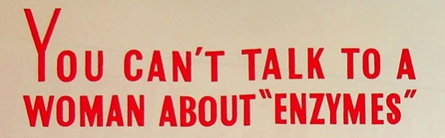

How women are discussed in the articles and advertisements in the Northwestern Miller throughout the 1930s is invariably situated within the male printing and advertising perspective. Even articles written by women primarily address the needs identified by those the magazine establishes are men – bakers, millers, advertisers.

Women writers largely addressed the “woman problem” in the milling and grain industry. The woman problem identified in the magazine – how to effectively sell to the millions of America’s housewives with purchasing power for their families.

‘Be yourselves, ladies!’ reads the headline of a subsection in Robert E. Sterling’s editorial from January 24th, 1934. The subsection of the editorial is Sterling’s commentary on Mrs. Harvey E. Wiley, who, according to the editor, continued to campaign with a pro-bread consumption stance, for her husband’s political causes after his death. Sterling’s comment presents the editorial opinion on the role of women in the industry in a multi-layered and reductive way. He says,

‘We began digging into this historical continuity [of women continuing their husbands’ business and causes after becoming widowed] [in] wonderment that, in these times of presumed rugged individualism among women, there should be so many of them trying to fit their dainty shoes into the footprints of their late lamenteds. It is now an established political tradition that senators, congressmen, governors, sheriffs, postmasters, etc. should be succeeded by their widows. The vogue carries over into business, and the arts, professions and sciences. This must often be more of a compliment to the deceased than it is an evidence of strong identities and originalities among the relicts. But probably it is all right – we were just idly wondering.’

This passage does not acknowledge the profound difficulty women faced in accessing careers on their own – due in large part to prejudice and misogyny such as the kind Sterling shows here. Sterling’s implication that the ‘dainty’ feet cannot fill the shoes of their departed husbands, and his assertion that the success of this category of women is due to the efforts of their dead husbands is an excellent example of what women like crop expert E. Cora Hind (whose career is explored below) faced in their careers in this industry. In this passage, Sterling also identifies the gender in power in the industry with his last line – ‘we were just idly wondering.’ The ‘we’ in this case being men – the men who ran not just the Northwestern Miller, but the milling and grain industry in North America. This passage also highlights the culturally prevailing idea that womens’ work was perceived as being of lesser value to industry, in this case, the milling and grain industry.

E Cora Hind

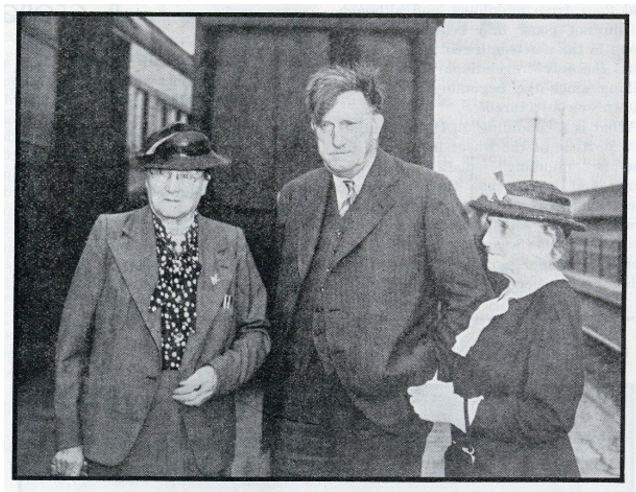

E. Cora Hind (b. 1861- d. 1942) was a world-renowned grain crop estimator, journalist, and editor of the Winnipeg Free Press. During her lifetime, she aided the campaign for women’s right to vote in Canada, and toured the world to analyse the international agricultural scene in the 1930s.

According to John W. Dafoe (1937), editor of the Winnipeg Free Press and writer of the foreword to Hind’s autobiography, Seeing for Myself, Hind burst onto the agricultural scene in 1904, when:

‘A promising wheat crop in Western Canada was attacked by black rust – the first appearance of this plague. So-called wheat “experts” from Chicago rushed to “kill the crop” (…) and finally got the [predicted] wheat yield for the season whittled down to 35 million bushels. [To challenge this assessment] Miss Hind (…) undertook to make an estimate for the Free Press based on an actual inspection of the crop. [Hind gave] an estimate of 55 million bushels. (…) The close of the crop year showed yield of something over 54 million bushels [and the] reputation of Miss Hind as a real expert was made, subject of course to the possibility that subsequently she might lose it. But in fact this she never did.’

The Northwestern Miller’s treatment of Hind simultaneously acknowledges her importance in the grain industry while persistently highlighting her gender. In the October 12th, 1932 article about her voyage on the ‘Juventus’ ship to Europe in her 70s, the article lists Hind’s accomplishments in the industry as a woman – as ‘the first girl typist in Western Canada, and as such wrote the first brief use in the Manitoba courts, (…) the first woman to be granted a privilege ticket to the trading floor of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange,’ and so on.

After listing Hind’s accomplishments and contributions to the field, the article states,

‘Hind has been described as “a woman who can do a man’s work and yet remain womanly.” True, she wears mannish clothes in her field work because they are comfortable, but she is as fond of pretty clothes as any other normal woman and takes a particular delight in a woman’s hobby of getting a “bargain” in clothes.’

Sterling’s view of women does not, however, completely pervade and affect how Hind is covered in the magazine subsequently. In the ‘European’ section of the November 25th, 1935 Northwestern Miller, the European Branch Manager, C.F.G. Raikes gives a contrastingly blunt summary of Hind’s ‘trade survey of the wheat importing and exporting countries of the world for the Winnipeg Free Press’ which does not unnecessarily point out her gender beyond the basic pronouns ‘she’ and ‘her.’ By October 1935, in his editor’s note at the end of Hind’s feature article ‘Soviet Russia’s Perennial Wheat Project,’ Sterling says,

‘Much that she has to report for the readers of her newspapers [the Winnipeg Free Press] will be of interest to the readers of The Northwestern Miller, to whom she is well-known as one of the foremost crop estimators in the world.’

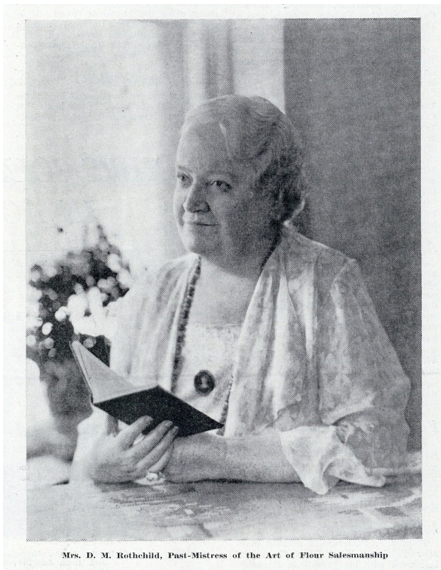

‘Half a Century of Masterly Feminine Flour Salesmanship’ reads the title of the August 2nd, 1933 article about Diza M. Kimball Rothchild, the export manager for the Stanard-Tilton Milling Company in St. Louis, Missouri. Like Kozmin-Reznichenko and Hind, Rothchild’s contribution to the industry is inextricably linked to her gender by the article title.

The article commends the ‘progressive spirit of E.O. Stanard, then president of the [Stanard-Tilton] company, who (…) ‘saw how’ Mrs. Rothchild and her abilities as a stenographer and ‘one of the first operators of a typewriter in a mill office’ ‘could be used to good advantage in the milling business.’ She began her career by ‘composing imaginary sales letters on the typewriter,’ ‘began to wonder how good or bad they were,’ and was encouraged to ‘send some of them out to prospective customers and see what the results were.’

The response, according to the article, was so ‘gratifying’ that ‘before long she was writing letters to all parts of the United States and signing them with the company’s signature.’

She shortly began venturing into foreign markets where she ‘was to have her greatest success.’ The article notes that ‘many of her foreign customers, probably to this day [1933], do not know that “D.M. Rothchild” who is their contact with the Stanard-Tilton Milling Co. is a woman.’ The article largely ascribed her success as being due to the perspicacity of her gender.

Like with the profile on E. Cora Hind, so the Northwestern Miller reassures its readers that ‘although she [Rothchild] has led an active business life since she was a young girl with auburn curls down her back, she has not neglected her home life nor her womanly pursuits such as knitting and needlework in both which she is very proficient.’ The writer of this profile, alongside the editorial vision for the Northwestern Miller presents Rothchild as being successful in business both in spite of and because of gender norms of the time. I.e., would a man have had the typist skills that were necessary to kickstart Rothchild’s career?

Mrs. William Waterman

According to R.A. Sullivan’s short report on Mrs. Waterman, titled ‘Feminine touch in flour,’ she is one of the widows, decried by Sterling in his editorial from January, the previous month, ‘trying to fit their dainty shoes into the footprints of their late lamenteds.’ ‘She assumed leadership of the organisation [J.S. Waterman & Co.one of the leading flour and brokerage firms of the South, located in New Orleans], succeeding the founder of the company, J.S. Waterman Sr. who died in October [1933]’, reports the article. She is quoted saying,

‘My husband often brought his problems home and we thrashed them out. Thus, in reality, I find I know a great deal more about the business than I thought I did before I took charge. The long talks I had with my husband have given me an insight into the problems of management, which I apply daily.”

The final line of the article – ‘Mrs. Waterman is the mother of four children.’

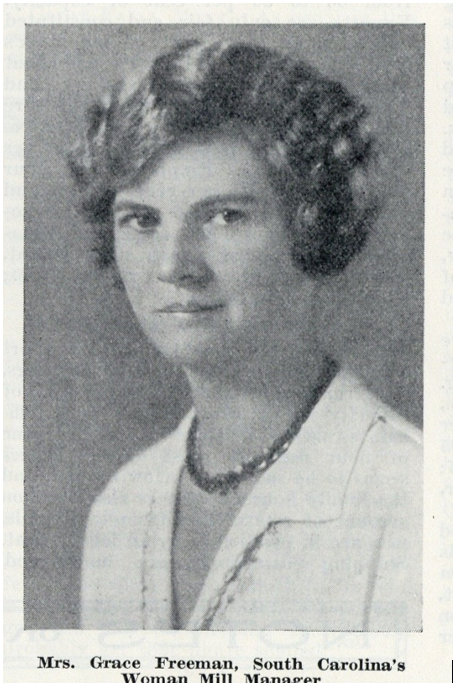

In the 1931 article ‘A Woman Flour Mill Executive,’ S.F. Poindexter introduced Mrs. Grace Freeman, General Manager of City Milling in Marshall, North Carolina, as ‘one of the few woman millers in the world.’ The article reads, ‘while many other women in these modern times have taken up aviation, business professions, and other masculine lines of endeavor, Mrs. Freeman has been actively engaged in one of the [most] difficult jobs of all – that of supplying the daily bread for hundreds of people who are distributed not only over Madison County, but in many other sections of western North Carolina.’

The author says that the City Mill Co. was a ‘product of hard work and resourcefulness on the part of [Grace Freeman], her husband, Fred E. Freeman, and associates, who founded the business.’ Poindexter follows up to reassure readers that Fred E. Freeman ‘is also connected with the mill operations.’ From this, we suppose that Mr. Freeman has some to do with the mill operations, but that Mrs. Freeman does indeed run it.

As with, Hind, et. al., above, the article covers Freeman’s feminine pursuits thusly:

‘Besides working six days a week at the mill, Mrs. Freeman finds time to take part in church and civic affairs in her town. She is an active member of the Order of the Eastern Star and has been a member of the chapter at Marshall for a number of years.’

Nan Cullen

Nan Cullen, owner of the King Kullen grocery stores in Long Island is another of Sterling’s ‘dainty-footed’ widows.’ As Arthur H. Larabee writes in his article ‘King Cullen’s Widow Carries on Super Pioneer’s Policies’ for the August 17th, 1938 issue of the Northwestern Miller, this particular one is the ‘attractive, vivacious widow of Michael Cullen’ a pioneer of the early American supermarket industry. Nan and Michael Cullen started the King Kullen supermarket chain, and after Michael died in 1936, his widow took over his leadership role in the business.

Larabee’s article quotes Nan Cullen directly. She says, according to Larabee,

‘I consider these markets [the new King Kullen markets she opened after her husband’s death] a monument to my husband. (…) Not only is it why I am carrying on, but why I am planning to open more markets, just as my husband intended.’

Quite shrewdly here, she is utilising her husband’s memory in the business community and his ‘intentions’ as a shield behind which she can push forward the business on her own terms.

To hark back to Sterling’s comment about dainty feet filling their husbands’ footprints, according to Larabee, ‘Mrs. Cullen directs the operations of 17 huge markets with only five other executives, one of them her son, Jimmy. This seems remarkable when one considers that the 17 stores [did] a gross annual business of $8,000,000’ at the time of Larabee’s article. ‘The feminine point of view is readily adaptable to the making of flour as well as its utilization in the kitchen’.

Each of these profiles, barring Nan Cullen’s – which focuses on her accomplishments succeeding her husband’s death, makes the point of reassuring the Northwestern Miller readership that these ‘women in business’ still capably fulfil the social role and responsibilities assigned to women in the 1930s and the preceding decades – motherhood, shopping, community engagement, and more.

V.W. Morrow’s 1933 article ‘Milling as the Lady Miller Views It,’ gives us a sketch of the early 20th century workplace atmosphere in the business profile of Ida M. Randle, Treasurer and General Manager of the Moseley and Motley Milling Company in Rochester, New York. Morrow says,

‘When Miss [Ida] Randle [the subject of the article] started in the flour milling industry [25 years prior], women’s rights, privileges and opportunities were being talked about seriously in the business world after a long period in which the gentler sex had been held in a sort of petty bondage. (…) Conservative business men at that time [presumably 25 years prior to 1933] shrank somewhat from giving women a voice in management of business.’

The women in leadership profiled in the Northwestern Miller are unfailingly mentioned in capacity or competition to the opposite gender. They, from the perspective of the Northwestern Miller, overcome the inherent handicap that is being female and rise to the business-acuity of their male counterparts. Thus is the arc of their success and how they are able to be successful in business in the pages of Robert E. Sterling’s Northwestern Miller throughout the 1930s.