Everybody knows about the dangers of eating wild plants, and even experienced nature-lovers have to be careful when picking woodland mushrooms, berries or flowers for a foraged feast. I know from personal experience that eating a funny mushroom is absolutely not funny at all! These days we like to stick to good old reliable Tesco or Sainsbury’s, and if we’re feeling adventurous we might make the occasional foray into a rustic farmers’ market.

But what if the evil within was hidden in the most unassuming, the least-suspicious everyday staples of our diet? What if your daily bread was actually a daily dose of death?

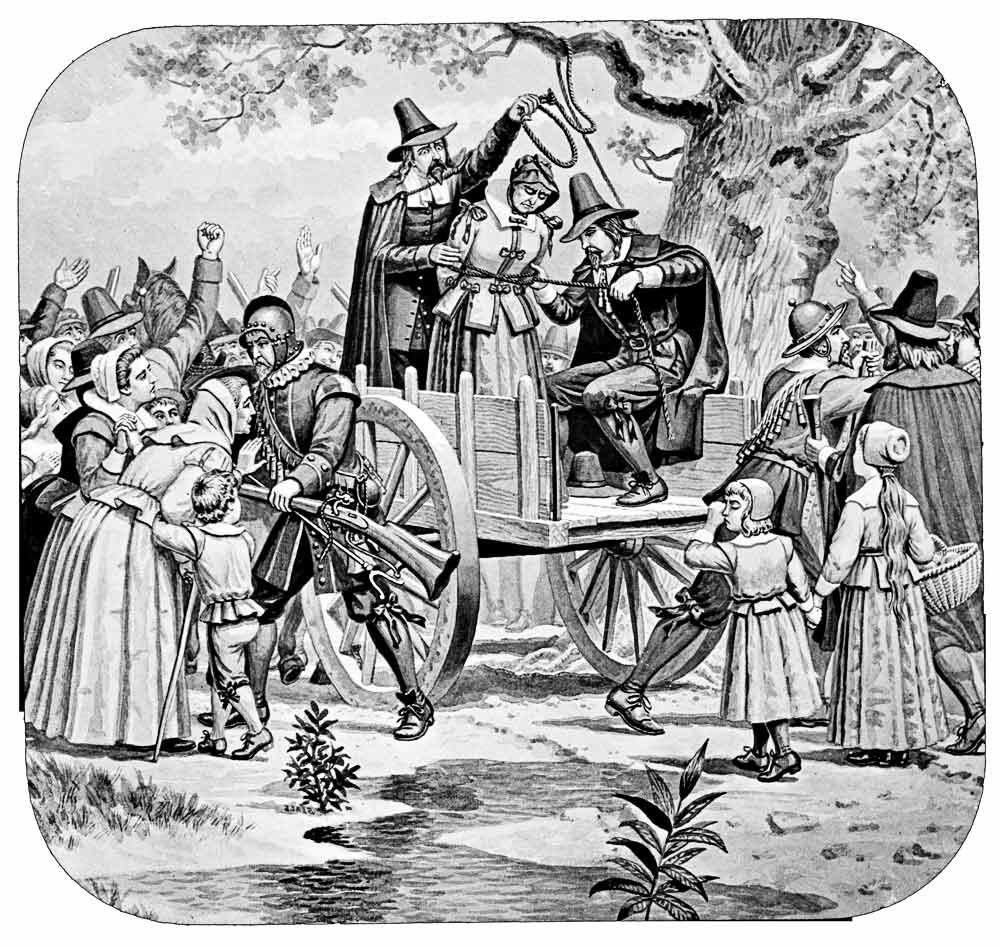

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Europe and America were swept by the witch craze: a plague of accusations of witchcraft, leading to thousands of grizzly deaths of innocent people; mostly poor, single women over the age of fifty. Probably the most infamous of all the witch hunts were those in the small Puritan village of Salem, Massachusetts, from 1692 to 1693.

As immortalised in Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, the trials start in 1692 when the young girls Betty Parris and Abigail Williams fall into a coma and begin exhibiting strange symptoms, including convulsions, delusions and incessant screaming. Rumours say that they are possessed by the devil; the town watches on in horror as more and more girls fall ill with this mysterious affliction, and it is not long until accusations of witchcraft are flying. Hysteria abounds and the townspeople decide to hunt down and execute all the witches of Salem – and by May 1692, nineteen people had been hanged, one had been crushed by stones and four had died in prison.

Ever since, historians and scientists have argued over the real cause of the Salem witch trials. Some truly people believed in the bewitchment; some thought it was fuelled by personal disputes, rivalries and politics getting out of hand, and others, believe it or not, put it down to a case of mere ‘mass female hysteria’ due to boredom. For centuries it was disputed – then in the latter half of the 20th century, new research was undertaken which threw the trials into a completely new light.

In the early 1970s, an American college student named Linnda Caporael became intrigued by the case, as many before her had done, and started to look into the possible causes. By 1976 Linnda, who was now a behavioural psychologist at New York’s Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, made a ground breaking discovery: the symptoms presented by the Salem ‘witches’ were very similar to those found in people who have taken the hallucinogenic drug LSD. Obviously LSD wasn’t a common recreational drug in the 1690s like it was in the 1970s – however, LSD is made from a derivative of ‘ergot’, a fungus that affects rye grain, wheat and other cereal grasses.

The website pbs.org has an article titled ‘The Salem Witch Trials: Clues and Evidence’ which states the following:

“Ergotism [also known as St Anthony’s Fire] is caused by the fungus Claviceps Purpurea. When first infected, the flowering head of a grain will spew out sweet, yellow-coloured mucus called ‘honey dew’, which contains fungal spores that can spread the disease. Eventually, the fungus invades the developing kernels of grain, taking them over with a network of filaments that turn the grains into purplish-black sclerotia – which is easily mistaken for large, discoloured grains of rye.

When ingested by humans, the alkaloids inside sclerotia affect the central nervous system and cause the contraction of smooth muscle – the muscles that make up the walls of veins and arteries, as well as the internal organs.

Toxicologists now know that eating ergot-contaminated food can lead to a convulsive disorder characterised by violent muscle spasms, vomiting, delusions, hallucinations, crawling sensations on the skin, and a host of other symptoms – all of which, Linnda Caporael noted, are present in the records of the Salem witchcraft trials.”

More research shows that other symptoms caused by ergot, or St Anthony’s Fire, include paranoia, cardiovascular trouble, and stillborn children. Ergot also seriously weakens the immune system. The muscle spasms suffered by ergot victims were called St. Vitus Dance, or ‘The Dance of Death’. This conjures up some quite eerie imagery, which has often been used in art, photographs, films and plays to shock and intrigue audience – and could be one of the reasons that Arthur Miller opens his play with the young girls dancing in a woodland clearing. You can see an example of plague victims doing the dance of death in the film The Seventh Seal by Ingmar Bergman, which begins and ends with the figure of Death leading the doomed in an eerie dance across a hilltop.

Ergot can also cause gangrene of the extremities due to constriction of blood supply, which eventually causes their fingers, toes, hands and feet to drop off – but not before they experience terrible burning sensations in these areas, giving the victims the feeling of being burned at the stake – hence the name ‘St Anthony’s Fire’ (St Anthony was an Egyptian monk who suffered considerable pain and hardships). These exact symptoms were seen in Salem and other towns in Essex County, Massachusetts: 24 of 30 purported victims of bewitchment, many of them children, “suffered from convulsions and the sensations of being pinched, pricked or bitten”.

So – is it possible that the victims of the Salem Witch Trials were high on LSD rather than on broomsticks? Did being ‘stoned’ lead to… being stoned? What evidence suggests that the case of Salem was down to ergot, and not something else?

For a start, ergot is known to thrive in warm, damp, rainy springs and summers, and outbreaks were typically seen across the globe when these conditions were rife. In the 1980s Mary Matossian, a history professor at the University of Maryland, conducted research into ergot poisoning and concluded that it was a possible cause of the symptoms of ‘demonic possession’. Dr Matossian studied seven centuries of demographics, weather, literature and crop records from Europe and America, and discovered that drops in population often followed diets heavy in rye bread and weather that favours ergot. She also found that witch hunts barely happened in places where people didn’t eat rye. ”New Englanders believed in witchcraft both before and after 1692,” she wrote, ”yet in no other year was there such severe persecution of witches.”

When both Mary Matossian and Lindda Caporael examined the diaries of Salem residents, they found that the perfect growing conditions for ergot had been present in 1691, when the rye for their bread would have been grown. In American colonies at that time, according to Dr Matossian, rye bread was a dietary staple and the crop was vulnerable to ergot. Plus, nearly all of the accusers lived in the western section of Salem village, a region of swampy meadows that would have been prime breeding ground for the fungus. From widths of tree rings formed during that period, she found that the growing season in eastern New England was abnormally cool between 1690 and 1692. Diaries kept in Boston during the intervening winters showed they were “very cold”. The summer of 1692, however, was dry, which could explain the abrupt end of the “bewitchments”: they had simply run out of infected bread.

Matossian’s evidence for the connection between the witchcraft symptoms and weather conditions continues: apparently, the weather was ideal for ergot during the early years of the Great Plague (also known as the Black Death), which peaked from 1347 to 1351, killing an estimated 75 – 200 million people.

‘Madness’ was commonplace and well-known in plague victims, and in fact, Matossian says that plague symptoms may often have been confused with those of ergotism, and suggests that the plague and ergotism probably co-existed, as ergot would suppress the immune system, making people more vulnerable to the plague (especially children, who have naturally weaker immune systems). Records of plague deaths show huge regional variations, suggesting that the plague may have followed pockets of rye ergot.

But despite the wide knowledge of these symptoms in connection to the plague, for some reason when the plague had not been diagnosed, the ‘madness’ was taken for witchcraft instead. This could have been partly because of the way the disease was received: one theory says that it could have all been down to Salem’s village doctor, who was unaware of ergotism as a disease but was strongly religious, and attributed the strange symptoms to an unknown evil: witchcraft. Once he made this claim, the girls went along with it and the suggestible townsfolk followed, and thus the trials began: with accusations of witchcraft being targeted at the outcasts of society, or simply people who were disliked – and petty personal disputes and village politics were fuel for the fire.

There is compelling evidence all around, but I would suggest that the symptoms of ergotism weren’t picked up on and were instead attributed to witchcraft because of the politics going on in Salem at the time.

In the ergot victims, people simply looked for what they knew as typical ‘witchcraft symptoms’ for evidence of demonic possession, and symptoms which correlated with an actual disease and not with their idea of witchcraft (like nausea, vomiting and ravenous hunger) were simply discounted.

The people saw what they wanted to see, and the result was deaths of more people than ergotism alone would ever have taken. In this case, the most infectious and deadly disease was rumour, and the evil was not just on the supper table, but in the anger, jealousy and maliciousness of mankind.

References:

https://www.britannica.com/story/how-rye-bread-may-have-caused-the-salem-witch-trials:

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/witches-curse-clues-evidence/1501/

https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1037.htm:

https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=14891

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/08/29/us/new-study-backs-thesis-on-witches.html