| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this summarises Chapter 8. This period to the mid-18th century saw significant developments in the technology of corn milling, changes in land ownership and a rise in population as standards of living improved. |

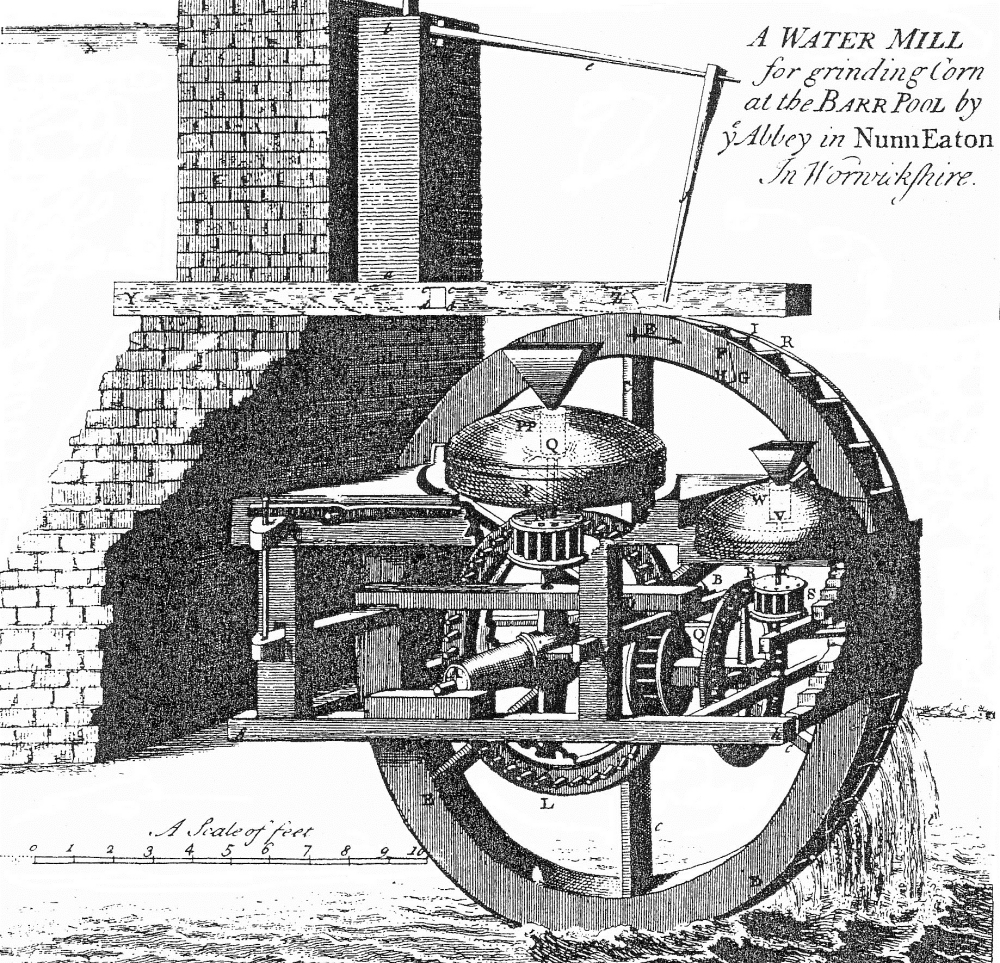

| Before the end of the 16th century there is evidence of improvements in mill gearing, which enabled two pairs of millstones to be driven by a single waterwheel. Because of the additional gearing, the runner of the second pair of stones was faster rotating. In the 1590s a watermill at Sidmouth, Devon was described as a ‘treble mill’ with a waterwheel driving two pairs of stones, one for clean corn and the other for malt. The so-called treble mill gearing became more widespread during the 17th century, although it was not illustrated until the early 1720s. |

The Town Mill at Lyme Regis, Dorset, which was rebuilt after being destroyed by fire in the siege of the town in 1644, during the Civil War, had two waterwheels each driving a pair of millstones in 1675; in 1728 a ‘treble malt mill’ was added. Survival of a treble mill layout is extremely rare, one of the last complete examples being Arden Mill, a small estate mill in a remote location in the North York Moors.

One of the few surviving examples of treble mill gearing at Arden Mill, North Yorkshire (Photo S. Buckland, Mills Archive Collection, JSPB-1127475)

Where there were two or more mills under one roof, the waterwheels that drove each pair of stones could be located side by side in a central wheelpit, at both ends of the building or in line, either one behind the other, or partially overlapping. Larger waterwheels were required to provide sufficient power to run two or more pairs of millstones, usually through spur gearing which, by the mid 18th century, dominated gearing layout in both watermills and windmills.

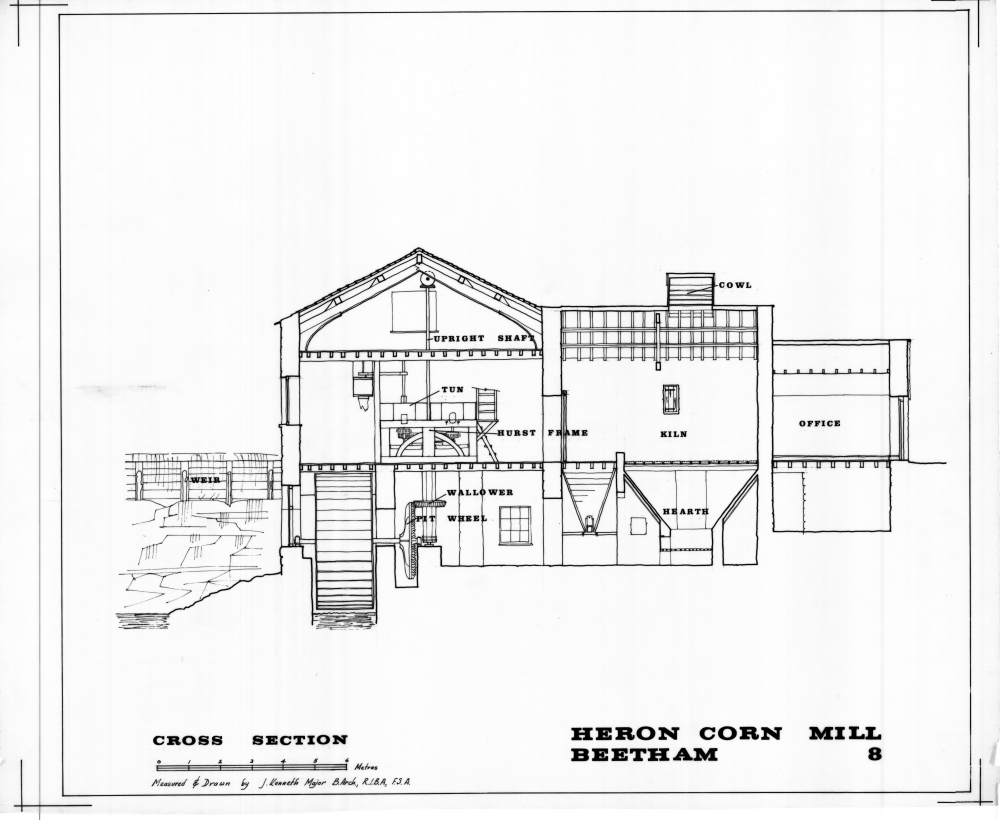

Cross section Heron Corn Mill, Cumbria showing the millstones, driven through spur gearing, and the adjoining kiln for drying oats (JKMC-DRW-33-W1-009)

| Spur gearing, with a vertical shaft carrying a large diameter horizontal gear wheel from which drives were taken by small gear wheels (stone nuts) to millstones or ancillary machinery, is illustrated in late medieval sources, but probably only became a practical reality in the 17th century. An advantage of spur gearing was that the millstones ran at the same speed and their diameters could be standardised within each mill. Interestingly, larger diameter stones tend to be found in mills in the north of England. Spur gearing was to become particularly well suited to the circular multi-floor plan of tower mills, allowing two, three and sometimes more pairs of stones to be grouped around the central shaft. |

| Heron Corn Mill, Beetham, Cumbria, represents an interesting regional type of watermill. Rebuilt in about 1740 as an oatmeal mill, it has four pairs of millstones under-driven by spur gearing from a single waterwheel, with ancillary equipment and a kiln for drying the oats prior to shelling and grinding. The millstones are set on a free-standing hurst frame, known locally as a lowder. The timber-framed and clad tower mill, popularly known as the smock mill, was also introduced, probably from the Netherlands, before the end of the 16th century. Initially designed for land drainage, it was quickly adapted by English millwrights to corn milling, the form becoming particularly dominant in Kent and the south-east of the country. |

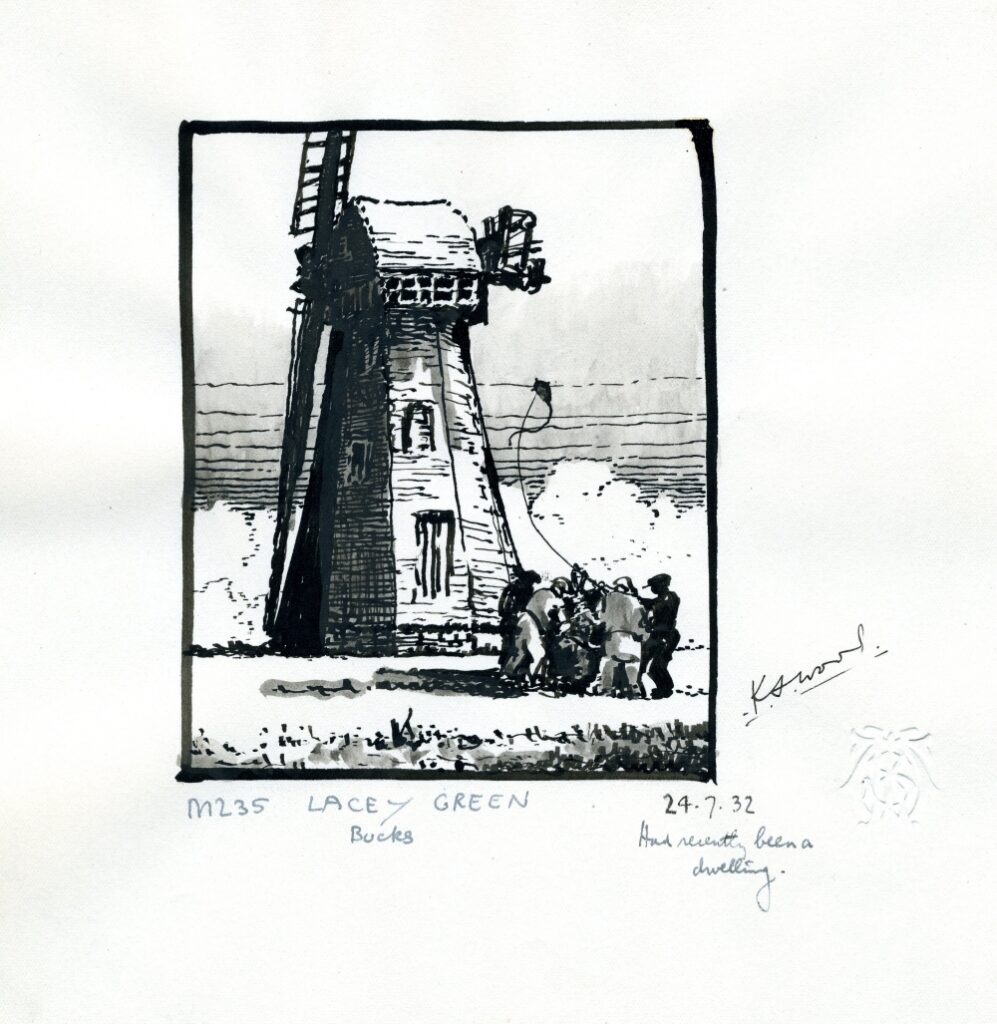

he windmill at Lacey Green, Buckinghamshire which was built c.1650 is believed to be England’s oldest surviving smock mill (Drawing K. Wood, Mills Archive Collection, Wood-M235)

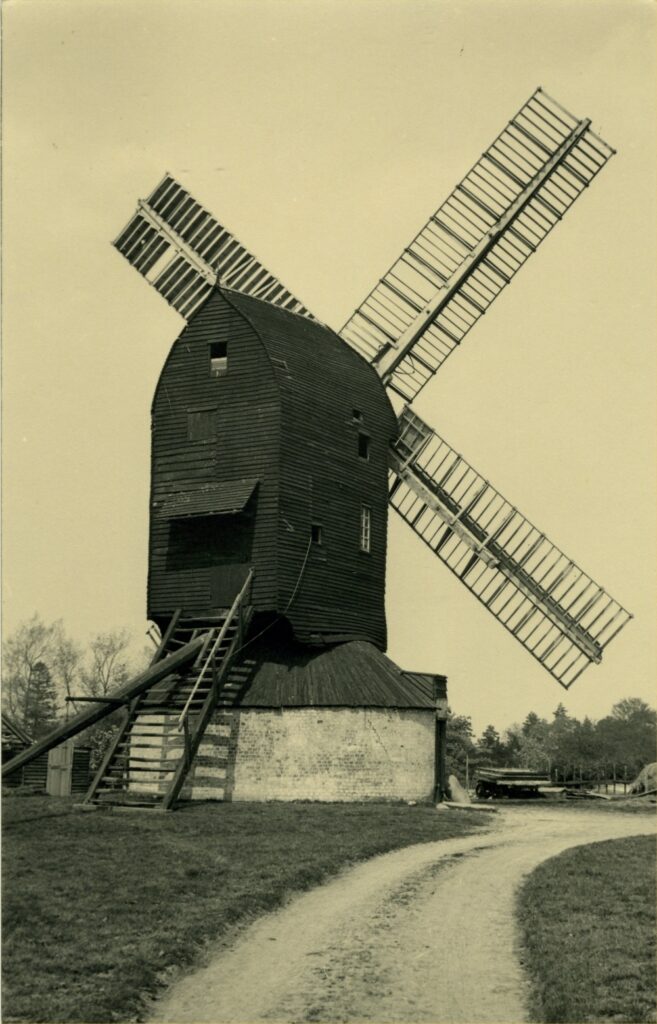

Post mills also continued to be built or rebuilt in those areas where timber-framing traditions were strong. In some post mills, such as at Cromer, Hertfordshire, where parts of the structure have been tree-ring dated, the post is older than the framing of the body, indicating that the mill has been rebuilt but that the original post has been reused.

Developments were also made to the gearing within post mills to enable them to drive two pairs of millstones, the stones being over-driven from the head or brake wheel and also a tail wheel mounted on the windshaft. This method of driving two pairs of stones is a form of layshaft drive, which is also found in watermills.

Outwood Mill, Surrey, a typical post-medieval post mill, originally built c.1665 with a roundhouse at two pairs of stones, one in the head and one in the tail (Photo H. E. S. Simmons, Mills Archive Collection, HESS-0995)

| Millstones continued to be imported from France and Germany, as they had been in the medieval period, French burrs and lava stones, known as blues, blacks or Cullins (from Cologne, the major shipping centre on the Rhine), being particularly favoured for milling wheaten flour. The most widespread English millstones were Peaks or grey stones, of Millstone Grit, quarried from suitable outcrops from the Derbyshire Peak District and the western and northern Pennines. Welsh stones, of sandstone conglomerate, were of more local importance, throughout Wales and also the south-west peninsula, where they appear to have been imported in increasing numbers during the post-medieval period. By the mid 18th century most of the developments in grain milling machinery had been made. The succeeding industrial period was to see an increased sophistication applied to such developments and more scientific and technical methods applied, such as analysis of waterwheel efficiency and gearing profiles. The empirical approach of millwrights whose technology and craft skills were those developed from carpenters and smiths in the later Middle Ages, became of necessity a more technical one. The complete article with further reading is here. |