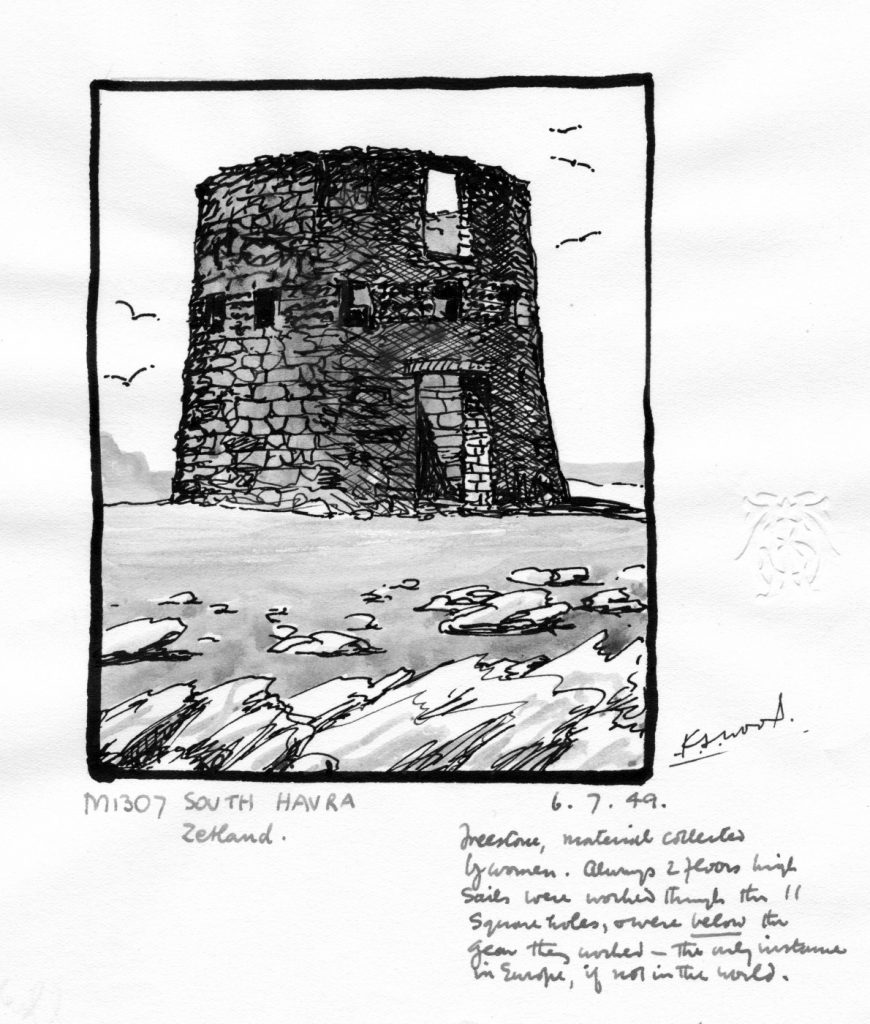

This sketch was drawn by the eccentric and enigmatic Karl Wood, only two years before he was sent to prison.

This sketch is from the Karl Wood Collection: it forms part of a project which he called Mühlendämmerungs, or Twilight of the Mills. It was a series of attractive ink sketches capturing the twilight era of Britain’s mills, from the 1920s to the 1950s. Wood’s aim was to publish a book of paintings of all 1,650 windmills that were still standing, with a foreword and introduction by Rex Wailes and Frank Brangwyn.

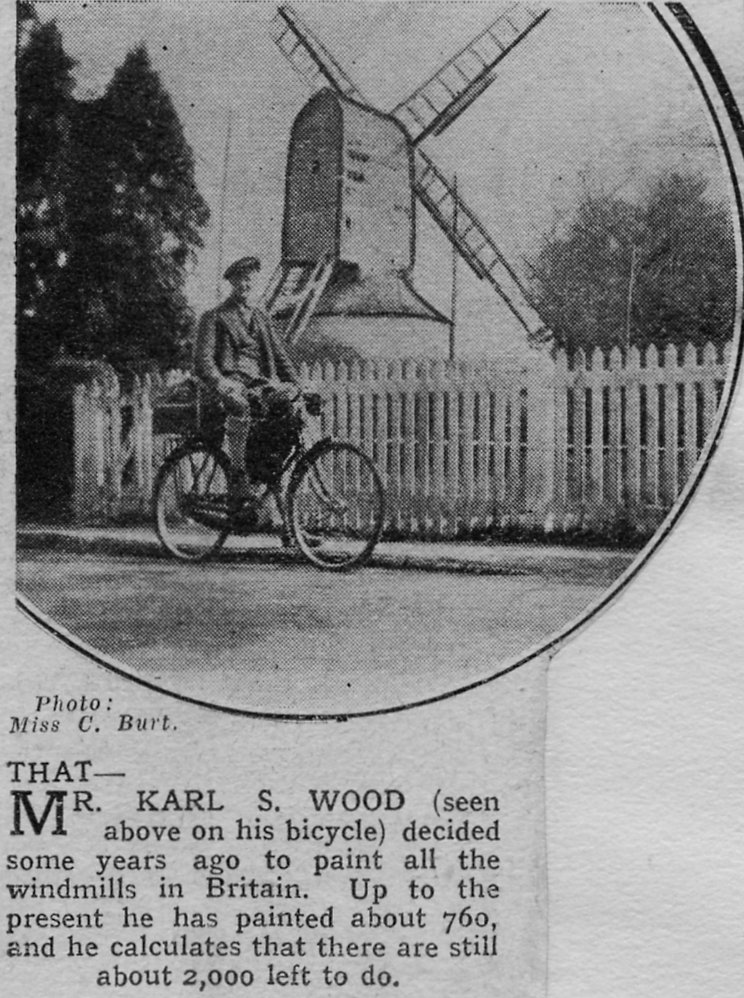

Wood’s ambitious mission to compile this book took him across the country, a project that spanned from 1926 until 1956, two years before his death. Impressively, he did almost all of his travelling by bicycle: by 1933, when he had drawn and recorded his first 450 windmills, Wood had already cycled 28,000 miles. After tracing his route on one occasion, he found that he had cycled 30 miles, visiting 13 mills in one day!

We can imagine that a large part of Wood’s journey was straightforward enough – sometimes he even took his art students with him on the easier trips (he was an art teacher at Gainsborough Grammar School). However, the exhibition that resulted in this particular Gem turned into a far more complex journey than he could have expected.

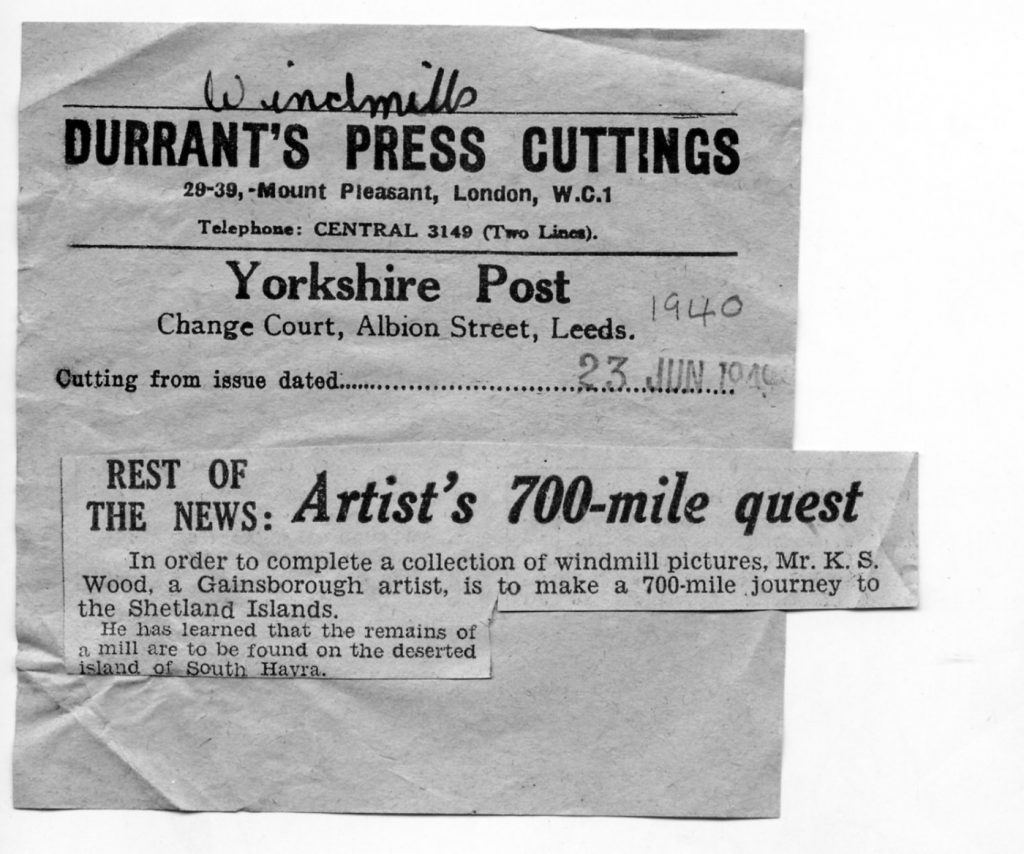

South Havra is a tiny isolated island off the West Coast of the Shetland Isles, which, by 1949, had lain abandoned and uninhabited for twenty years. Due to its remote location and lack of amenities it was not exactly a popular visitor destination – yet Wood was determined to succeed in his quest of visiting each and every windmill, and his stoic determination was to pay off. Catching the train from Gainsborough in the Midlands, he travelled to Aberdeen where he managed to catch a ship to Lerwick. From here, he was fortunate to find some locals, who agreed to take him in their small boat to South Havra and the mill. The Gem – the picture to the left that Wood drew of the mill on his arrival – is proof of his success!

This intrepid journey and successful completion of a difficult quest shows the extent of Karl Wood’s tenacity and dedication, and gives a taste of what a fascinating individual he was. Prior to this trip, he served with the Third Seaforth Highlanders in the First World War, suffering shrapnel wounds to the ankle whilst in France. He was promoted to the position of Corporal, but was then demoted back to Private under rather mysterious circumstances!

Wood remained rightly very proud of his war service, despite this potential unknown scandal. After the war he moved to Gainsborough, where his name became synonymous with windmills due to his passion for painting them. He lived a comfortable life working as both a hospital secretary and as an art teacher at Gainsborough Grammar School. He was widely liked and respected, with his eccentric nature and flambuoyant dress sense making him quite an unforgettable character. Wood’s homosexuality was an ‘open secret’; he had several relationships with men over the years (his diaries from his windmill expeditions hint at two ‘encounters’ during his visits – we can only imagine how they came about!). Whereas his sexuality would widely be accepted these days, unjustly and unfortunately for Wood, it was not the case in his lifetime: homosexuality being considered a criminal offense up until 1967. Regrettably, scandal seemed to follow Wood, and in a harrowing and unfortunate indident in 1951, Wood was charged with six accounts of what was then termed ‘gross indecency’ with three men, and was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. We can only imagine how difficult and unjust it must have felt for him for his sexuality to cause him to be classed as a criminal, and sadly he never truly recovered from the ordeal of prison.

Following his imprisonment, Wood moved to a Benedictine Priory near Moray, north-east Scotland. He had converted to Catholicism in his youth and remained devout throughout his life, serving at various times as organist, choirmaster and pageboy. At the priory he found solace: he became an Oblate (someone associated with a monastery, a bit like an honourary monk) and set up a stained glass workshop – both actions earning him great respect from the community.

Karl Wood passed away on the 10th January 1958, buried in the habit of a monk. The cause was tuberculosis, of which he had been suffering for some time. The Master of Oblates, recognising that Karl didn’t have much time left, served him his final communion – after which Wood passed peacefully away.

It is sad that Wood was never to achieve his dream of publishing a book of windmills, but the Mills Archive is very lucky to have all 1,385 (so close to the final goal of 1,650) of his completed sketches, depicting mills right across the country from the Shetlands to Cornwall. We are very pleased to be able to allow people to view these drawings – one of the most comprehensive collections of windmill documentation – and appreciate a lifetime of such dedicated work.

Gem from the Karl Wood Collection in our catalogue.

- Information kindly provided by Dr Tony Shaw.

- You can also read more on the Collection Museum’s website, run by Lincolnshire County Council; they hold a collection of Karl Wood’s original watercolour sketches at the Usher Gallery in Lincoln.

Related links

- Further Reading: Mills have inspired artists for hundreds of years. Whether in sketches, prints or watercolours you can learn all about the artistic soul of milling here.

- By Trawler from Aberdeen: Karl Wood isn’t our only Intrepid Explorer who has explored a mill on an isolated island. Click here to find out about David Jones’ expedition to the Faroe Islands.

- Detective Work at the Archive: Sometimes an archivist must be a detective to uncover the hidden stories behind the collections in their care. Learn all about how we uncovered the mysteries behind the Karl Wood Collection here.