A key type of publication, from the milling industry, are numerous educational resources, textbooks and pamphlets, produced to teach about milling and the milling process. Examples of these types of publication from the 19th and 20th centuries, housed at the Mills Archive, provide a way of tracking both the development of milling education and the milling industry itself.

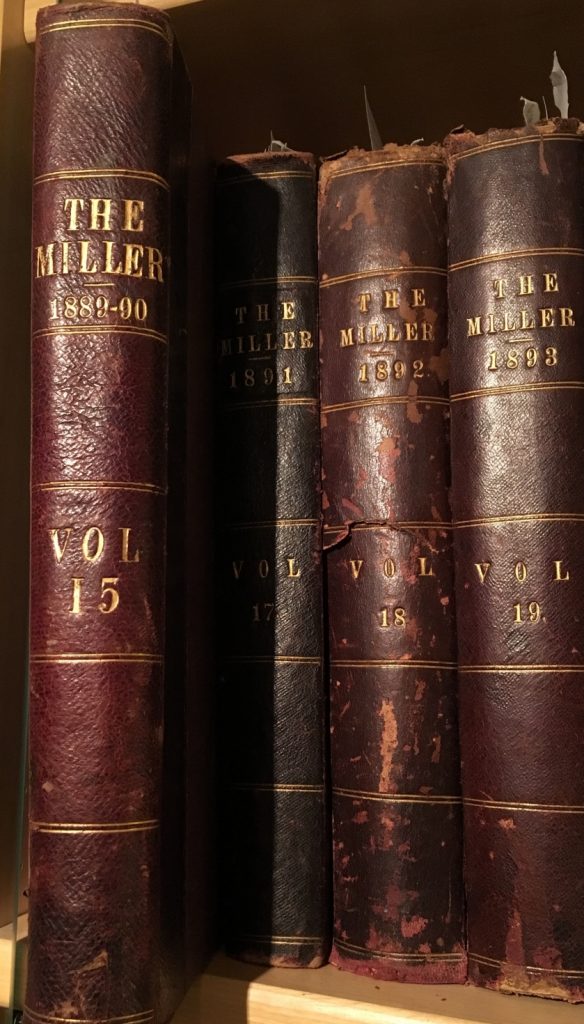

Interests in the scientific nature of milling began in the 1870s, alongside the development of roller milling. These scientific and technical advancements meant that it became necessary to publish new findings so millers could educate themselves about these changes. The first way this material was published was in journals, such as The Miller and Milling.

Another step forward in the advancement of education was when the City and Guilds of London Institute for the Advancement of Technical Education, started offering examinations in milling in 1883. In the first year 32 candidates sat the examination, 22 of which were successful (Jones, p.151). However, those that attended the examinations tended to either be masters or foremen, rather than the largest number of workers, operatives. Furthermore, the publications that were ‘noted in the City and Guilds syllabus’ were ‘in the German language, and no one has yet found it worth their time to translate them into English’ (Tattersall, TM, January 1887, p.499). As such, further developments were needed for milling education to reach a wider number of people.

The first development that took place was that H. H. P. Powles did find it worth his time to translate a German work. Friedrich Kick’s Flour Manufacture, a Treatise on Milling Science and Practice was translated into English in 1888, and was available to purchase on the British market. However, this work was written for a German audience with the German trade in mind, making it somewhat limited for a British audience.

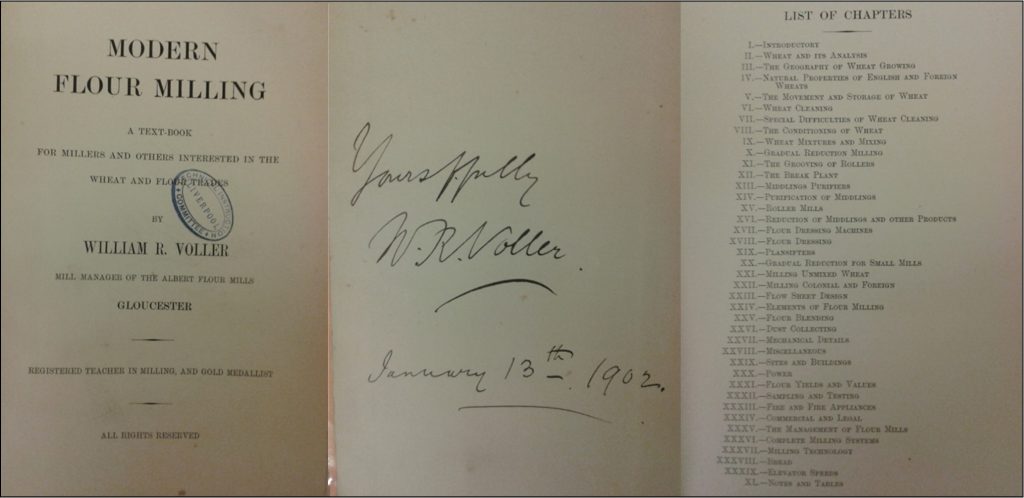

The first example of a suitable British text-book was not forthcoming until the year after the translation of Kick’s work. In 1889, William Voller wrote the ‘first substantial milling text by an English author’, Modern Flour Milling (Jones, p.156). William Voller had been one of the 22 who passed the exams held by the City and Guilds Institute in 1883. After that he had been invited to work at Albert Mills, Gloucester, where he had helped found the Gloucester Millers’ Technical Class. His voice had been one of the foremost in encouraging education and calling for the production of a text-book. In 1887, he even commented that the demand for a text-book was so great that one would inevitably be written, the only question was ‘who shall write it’ (Voller, TM, Sept 1887, p.308).

Voller’s Modern Flour Milling was a successful publication. Given that one of his motivations for writing it had been due to the number of requests for advice he received from around the country, this success is unsurprising. Indeed, a second edition was published only three years after the first with the third, extended edition published five years after the 2nd, in 1897. Voller’s publication was the first of its kind and going into the 20th century, ‘remained the clear leader in milling education’ .

Therefore, educational resources during the 19th century had been mainly comprised of articles from journals, translation of German works, such as Kick, and publications by William R. Voller. Indeed, The Miller advertised works in their ‘Books for Millers, bakers and kindred trades’ page. Works featured here could be purchased from the journal office, and the three ‘substantial works on milling technology’ advertised were Kick’s Flour Manufacture, Voller’s Modern Flour Milling, and Gradual Reduction Milling by the American Louis Gibson.

Despite this strong beginning, the 20th century still experienced issues with education, namely the discrepancies between masters and foremen and their operatives. An article published in The Miller in 1925, commentated that whilst master millers spent ‘an immense amount of thought and time on selection of machinery, and in keeping the plant up to date’, their selection of staff was ‘frequently done in a most haphazard way’ (‘The Renaissance of Technical Education’, p.361). Indeed, ‘little heed is paid to their qualifications or experience’ and in these conditions, it was ‘impossible to get the best out of a plant’ (‘The Renaissance of Technical Education’, p.361). Numerous ways of encouraging these operatives to attend classes, or gain further education, was suggested during the 1920s, including the possibility of part-time day classes for those aged 16 (‘Part-Time Day Classes’, p.375).

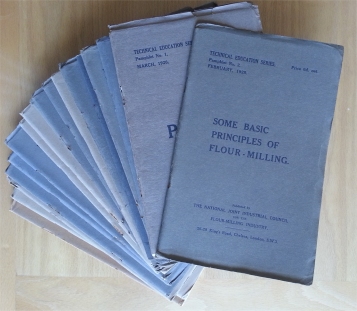

Furthermore, new publications, shorter than the text-books from the 19th century, were produced to make milling education more accessible to a wider audience. The National Joint Council for the Flour Milling Industry (NJIC) started producing technical education pamphlets in 1926. These NJIC publications were sold for a sixpence each and gave details about different aspects of the milling trade, from flour quality, to insurance, and historical studies of wheat conditioning. These publications printed until the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, gave a wide audience access to a variety of subjects, written by notable authors. Moreover, an ‘extensive correspondence text’ was appearing in Milling around this time, written by one Leslie Smith. It provided a comprehensive text ‘for use by students remote from main centres’, and was later published by Thomas Robinson & Son Ltd. in ‘inexpensive book form’ (Jones, p.312). These two different types of publications allowed milling teaching to reach a wider audience in a relatively cheap way.

As the 20th century progressed, the scientific nature of milling developed further. The firm of Henry Simon Ltd. was important in pioneering research and publishing findings to advance the milling industry. Ernest Simon, son of the founder, and Director of the firm after his father’s death, encouraged this research and himself wrote The Physical Science of Flour Milling in 1930. With this book, he was seeking to fill a gap in the literature ‘to deal with the principles of flour milling engineering, that is to say, with the physical science underlying the design of the machinery necessary to clean the wheat berry and to split it up into the desired products’ (Simon, p.5). The inclusion of the word ‘Science’ in the title emphasised the developments within the milling trade and the changing of emphasis from technology to science.

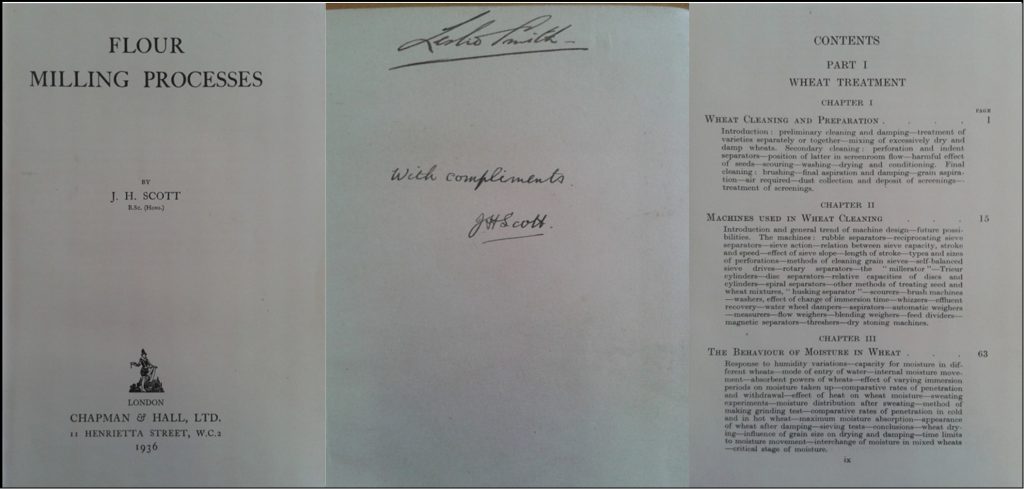

Moreover, the firm of Henry Simon Ltd. was indirectly responsible for other educational publications throughout the 20th century. In 1936, J. H. Scott, a member of Simon’s technical staff, produced his work Flour Milling Processes. This work was described by his boss, Sir Ernest Simon, as containing ‘valuable information, both theoretical and practical, which will be of real value both to students of flour milling and to practical flour millers’ (Scott, p.v).

Another Simon employee responsible for producing a key work within the industry was J. F. Lockwood, Simon’s chief milling expert. In 1945 he wrote ‘the modern classic Flour milling’ (Jones, p.312). Numerous editions of this book was published, with the fourth and last edition being published in 1962, described as finishing the ‘text book literature of the British milling industry’ which Voller had started (Jones, p.312). Indeed, Lockwood’s work was so valuable that it was translated into French, German, and Spanish, demonstrating a reversal of fortunes from when all British millers could rely on were foreign works translated into English, now English works were being translated into other languages.

Since Lockwood’s work, educational material and publications have continued to be produced, mainly by the National Association of British and Irish Millers (nabim). This association continues to produce material about different aspects of the milling trade, and runs a seven module distance learning programme. Milling education has therefore come a long way and no more do millers have to bemoan the lack of educational materials produced in Britain.

Along with tracing the development of educational publications in Britain, these works can be used to trace the development of the milling industry itself. For example, the third edition of Voller’s Modern Flour Milling, covers topics predominantly covering the technical and practical aspect of the milling trade, with chapters such as ‘Sites and Buildings’ and ‘Flow Sheet Design’. However, later publications, when roller milling was more established and the trade more developed, covered more scientific aspects of milling. Scott’s work from 1936 has a chapter on ‘The Behaviour of Moisture in Wheat’, along with chapters covering tests and experiments he had completed on break and reduction rolls. Lockwood’s third edition of Flour Milling, published in 1952, built on what these two authors had done, providing comprehensive guide to the entire milling process, with the first 15 chapters being devoted to the preparation of wheat for milling, a topic Voller had only spent 8 chapters on. As the trade developed, so did the literature that went alongside it.

Furthermore, developments within the trade also covered issues and concerns faced by millers. When Voller was writing in 1897, the greatest fear and concern for a miller was the threat of fire, as such he included a chapter on ‘Fire and Fire Appliances’. However, as precautions against this threat improved, with the installation of dust collectors and sprinkler systems, greater concern was given to the quality of wheat and flour through ‘The Control of Mill Pests’, a chapter in Lockwood’s book. The concerns addressed in these books allow us to see how concerns developed within the milling trade.

Sources:

‘Part-Time Day Classes’, The Miller, July 9, 1928, p.375.

‘The Renaissance of Technical Education’, The Miller, July 5, 1925, pp.361-2.

Gibson, Louis H., Gradual Reduction Milling (Minneapolis, 1885).

Kick, Friedrich, Flour Manufacture: A Treatise on Milling Science and Practice, trans. by H. H. P. Powles (London, 1888).

Lockwood, J. F., Flour Milling, 3rd edition (Liverpool, 1952).

Scott, J. H., Flour Milling Processes (London, 1936).

Simon, Ernest, The Physical Science of Flour Milling (Liverpool, 1930).

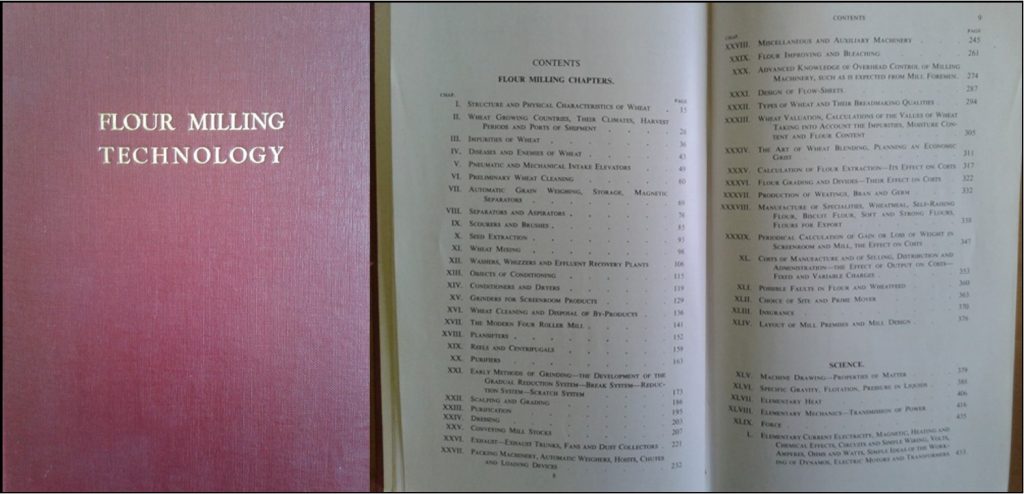

Smith, Leslie, Flour Milling Technology (1936).

Tattersall, The Miller, January 1887, p.499.

Voller, The Miller, Sept 1887, p.308.

Voller, William R., Modern Flour Milling, 3rd edition (Gloucester, 1897).