Michael Harverson

Michael Harverson (1937-2017) was one of the founding trustees of the Mills Archives. A particular interest of his was the mills of the Middle East, and in his collection we have several accounts of his travels, illustrated with photographs.

This newsletter contains another extract from Michael Harverson’s travelogue of his trip to Morocco in 1985 to research the watermills of the Atlas Mountains.

Mill Buildings

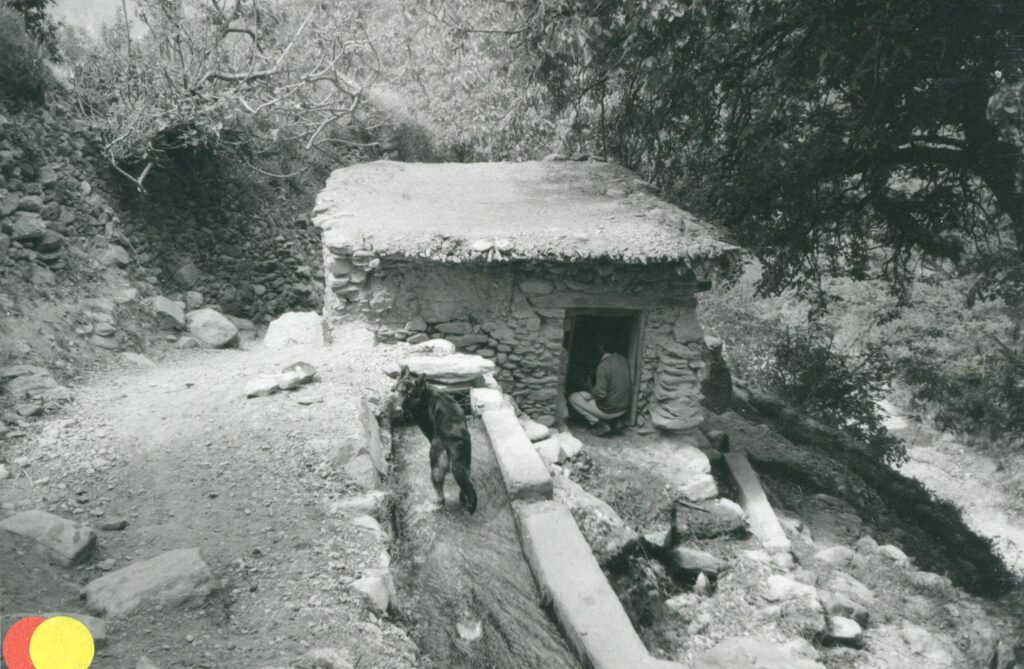

| Mills in the Atlas mountains are usually dry stone built, with a mud plastered roof of branches. Openings are few, often only the doorway. Large trees, especially walnuts, shade many mills. The mill shown below is fed from a deep storage pond (up to the left, off the photo). Here, unusually, the tail race turns left and runs underground for some fifty metres before emerging to water the irrigation ditches. |

Leats

| The headrace of these mills may be the stream itself, but more usually the water is diverted along a leat from higher up the valley. At Aït Sual (below) a dog stands where the leat drops down the chute to turn the mill in whose doorway his master crouches; when necessary, the water can be diverted round the lower side of the mill; far below is the stream bed: the water in the leat has been drawn off from it higher up in its course. |

Waterwheels

| The water falls from the leat dam down a wooden chute and strikes the blades of the horizontal wheel arranged in an inverted cone to work the mill. A board on a simple, supported pivot and pole arrangement deflects the water away from the wheel when the mill is to be stopped – the system is shown clearly in a plaster grinding mill at Sefrou at a time when the water supply to the wheel is minimal in any case. |

| The blades are morticed into the hub, closely packed together, with as many as thirty forming the pattern seen in the image above. Nails are not used, the 40cm. long blades being driven into the hub, often alternately up and down in order to make a tight fit at the hub end. The tips, however, should be roughly in the same plane and 30cm away from the shaft. This should give a smaller angle of about 30° between blades and shaft, but this varies considerably from area to area, as can be seen from the images below. With a base diameter of the hub of c.15-20 cm. this gives a total diameter of the wheel of at least 75cm., larger in most cases than that of the stones above. Along roughly two thirds of its length each blade is furrowed at the main point of impact of the water falling from the chute. The wheel is one of the more vulnerable parts of the mill, its efficiency impaired at times by stones, twigs, weed, even dead toads, collecting within it, or by blades becoming dislodged or broken. |

Chute and Deflector

| In these Ounein mills the deflector is turned into and out of position at the foot of the water chute. When water is flowing in it is deflected up over the wheel, which remains stationary. |

| This open chute, formed from a hollowed out tree trunk, often poplar, is typical of Atlas mill construction. The top is never covered except where it passes through the base of the back wall: then an old millstone is often placed over it. |

Transmission

| The wheel itself, consisting of blades and hub, terminates in a wide slot or deeply recessed top, into which the narrower main shaft is firmly wedged. The length of this pole, whose diameter tapers from c. 15cm to c. 8cm, varies with the depth of the wheelhouse. Near the top an iron spindle is inserted, the wooden shaft being banded and wedged, and this passes through a wooden bearing in the bedstone and into the slot in the rynd supporting the runner stone. The weight of the runner and the transmission to it of the water power are thus both dependent on this slender shaft, generally soaked by the water splashing off the revolving wheel or the deflector plank. The image below shows the steel spindle and its steel bearing: the size of a shilling and set into a larger square of steel in a slot in the footbeam. Like the copper pennies serving a similar function once in some British mills, the steel shilling needs frequent replacing. |

Deflector Rod and Lightening Controls

| A vertical pole beside the grinding area determines the gap between the millstones: as it is raised slightly and chocked up, the runner stone is brought closer to the bedstone. The metal bar protruding from the centre of the eye of the stone is the tip of the other end of this lightening mechanism: the runner stone balanced on a steel rynd, slotted into its working face and held at the required height by the lightening spindle. |

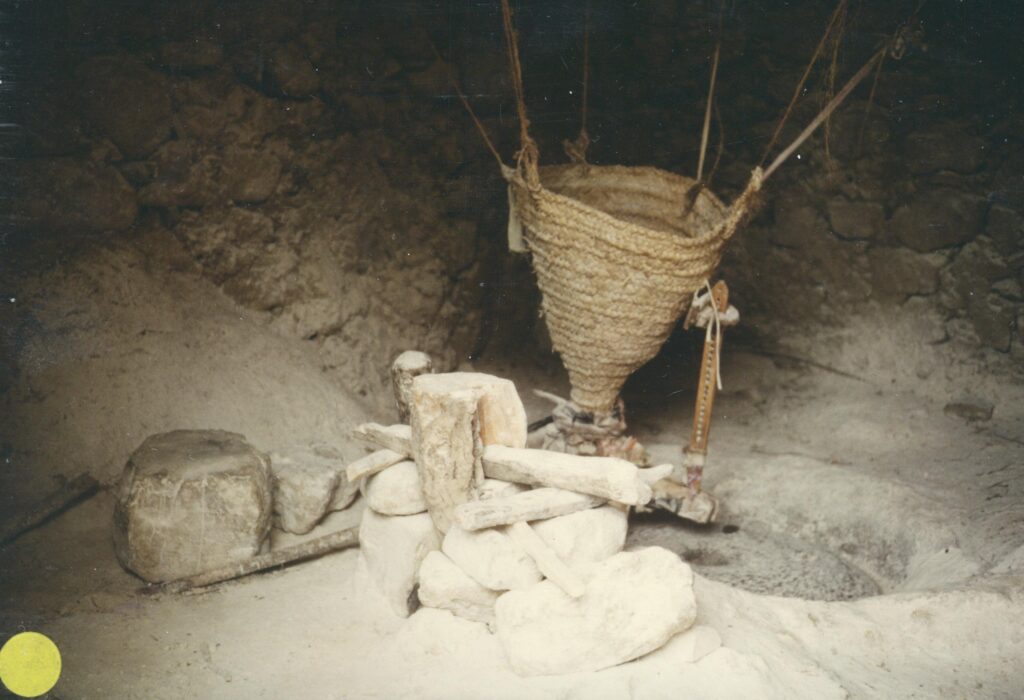

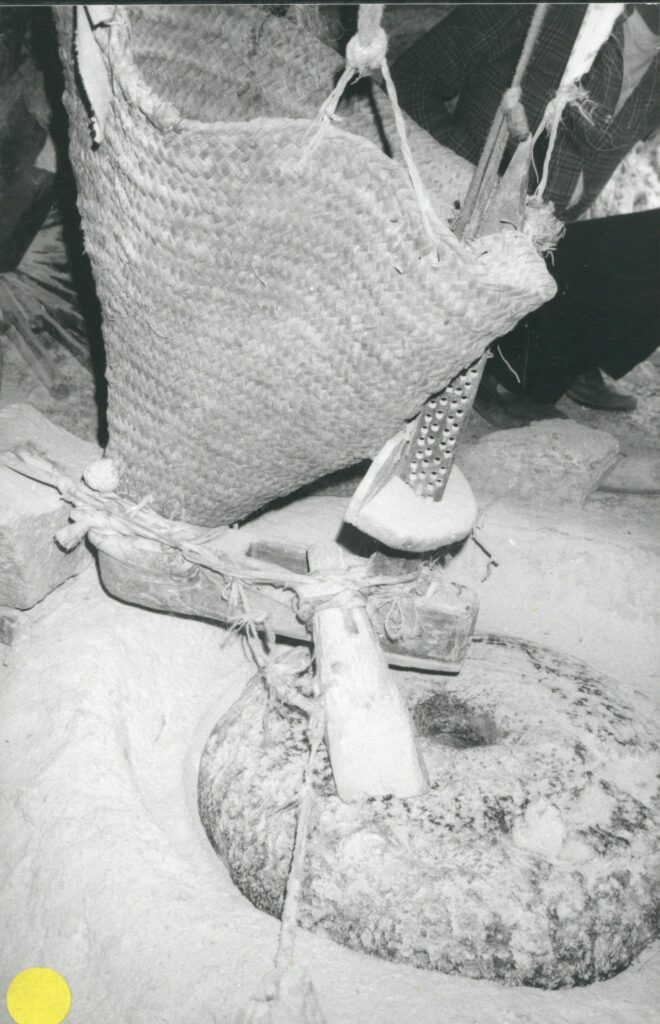

Hoppers

| The majority of the Atlas mills visited had a woven basket or small wooden hopper slung from the ceiling on wires, ropes or crooked sticks, e.g., at Aït Tashrift and Sefrou above. The inverted triangular pyramid at Skoura is made of galvanised iron and contains, in this case, a familiar basket also. The wooden hopper at Goulmima, below, is supported on a European style horse. |

| The grinding places are worthy of comment in each case, wooden tuns encasing the stones as in an English mill being unknown here. Flour collects in a pit, sometimes incorporating an old bucket, on one side of the stones. At Sefrou the stones are girdled by a woven strip, here drawn open for observation, which prevents the flour flying in all directions. The stones at Aït Tashrift and Goulmima have a low mud/cement surround (tall enough to support the horse at Goulmima), while Skoura has a wide, neat area around the carefully paired stones. In these three cases the operator is kept busy during grinding: he sweeps the flour into the pit, using a bunch of dried palm leaves or small twigs. |

Feed to the Stones

Maize drops into the eye of the stones at Aït Bou Guemmez. The mace (the metal tip of the drive shaft from the wheel) can be seen where it passes through a slot in the rynd, on which the runner stone is balanced.

The height of the shoe above the eye is controlled by a twisted string at Sefrou.

Where hoppers are absent, the customer feeds the stones by hand: at Tagounit and Takoucht (below) maize is being ground for the Ramadan fast-breaking soup. The geometrical decoration on the 64 cm stone at Tagounit is rare.

Maize being ground, Aït Bou Guemmez

Feed Shoe Controls

| If grain passes in too great a quantity down the shoe from the hopper into the eye, the stones will become clogged; if too small, there is a danger that the underemployed stones, spinning fast with no scattered layer of grain between them to be reduced to flour, will damage themselves. Most Atlas mills that have woven hoppers overcome this problem by having attached to the front end of the shoe a perforated board which slightly raises or lowers the shoe over the eye, depending on where strings (Aït Imi below left), or a wooden bracket (Aït Tashrift, centre and Taourirt, right), firmly fixed to the front of the hopper, are pegged in position. |

Hoppers and millstones

“The Dogs”

| A constant trickle of grain along the shoe is assured by a chunky wooden peg that vibrates it. This peg, carefully carved and strung in place at Ouzoud, below, or roughly shaped and hung over the edge of the shoe, joggles over the uneven upper surface of the revolving runner stone. This device is known as ‘the dog’ (la chienne), for dubious onomatopoeic reasons, just as ‘stork’ in Persian, ‘click’ and ‘clapper’ in the Orkneys and the Shetlands, or indeed the English Vitruvian mill’s damsel which fulfils the same function as the vibrating trail-stick of the other horizontal mills referred to. |

Millstones

| In poor, remote mountain communities millstones tend to be quarried as locally as possible: in the large valley of Ounein a part time millwright himself went in search of suitable stone when necessary. Such stones are usually small – av. 60cm – with a shallow dome shape for the runner. They represent perhaps the most expensive item in the building and equipping of a small mill: the runner at Aït Tashrift in 1984 cost 600 dirhams (c. £30); the owner/builder/miller himself fashioned the bedstone. In the Middle Atlas a new pair obtained from My Elmehdi, an old carpenter and millwright in Sefrou well known in the area, cost only 500 dirhams. One such pair, initially dressed in the town and delivered by lorry, were much broader and thinner than in Ounein: only 12cm thick when new, yet said to last for 30 years. That working life depends of course on the degree of use. All stones seen in Morcco were in one piece i.e., no composite or composition stones, both familiar in European mills. |