Stephen Buckland

| This is an abridged version of an unpublished typescript by Stephen Buckland (1935-2006) which is held in the Archive’s collections. You can read the full transcription here: https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/newgate-prison-mill-1752-unpublished. | |

Newgate Prison

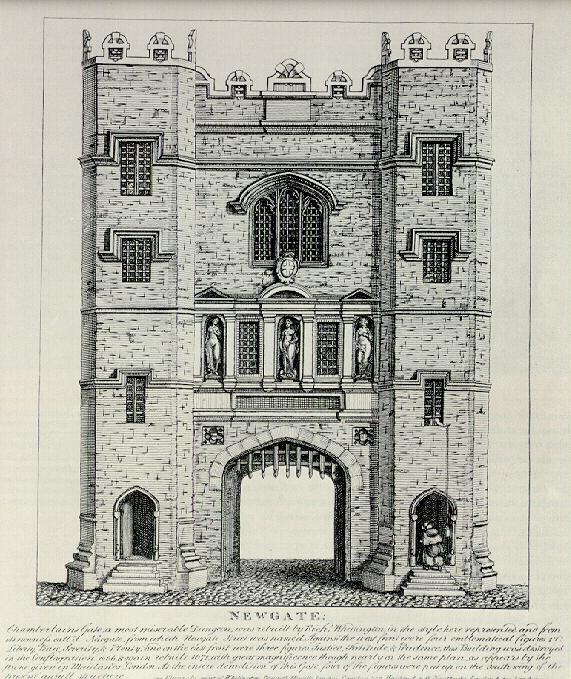

| The ancient prison of Newgate, near the present Old Bailey, was built originally in the 12th century within one of the gates in the city wall. It was extended and rebuilt many times, including by Sir Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Nearly a century later, the author William Maitland was to remark: Newgate, considered as a Prison, is a Structure of more Cost and Beauty than was necessary, because the Sumptuousness of the Outside but aggravates the Misery of the Wretches within. Newgate, according to Maitland, was a dismal place within. The Prisoners are sometimes packed so close together, and the Air so corrupted by their Stench and Nastiness, that it occasions a Disease called the Gaol-Distemper, of which they die by Dozens, and Cart-loads of them are carried out and thrown into a Pit in the Church-yard of Christ-Church, without Ceremony; and so infectious is this Distemper, that several Judges, Jurymen, and Lawyers, &c. have taken it of the Prisoners, when they have been brought to the Old-Baily to be tried, and died soon after; of which we have had an Instance within these seven Years.(William Maitland, History … of London, ii (1756), p.951). Manual ventilators were fitted in Newgate when Sir Richard Hoare was lord mayor (1745-6), and ventilated five chief wards (rooms) where the women were. A little toy size windmill, probably with copper or brass sails, twirling in the mouth of the extraction trunk, caused a bell to ring continuously, in order to keep the men labouring at the ventilators on their toes (the same system was used at Winchester hospital). These ventilators fell into disuse however, and a major outbreak of gaol fever (typhus) in 1750 spread to the court of the Old Bailey, leading to the question of whether to rebuild the prison. |

Stephen Hales

| In May 1750 the physiologist Stephen Hales (1677-1761) attended the Old Bailey and noticed the offensive smell. Hales had been carrying out experimental work on animal respiration and had discovered plant transpiration, deducing that the loss of water from the leaves of plants drives the flow of water up from their roots. This led him to turn his attention to the design of ventilating systems for ships and prisons, which work on a similar principle. Some of his extracting ventilating ducts or trunks were worked by little windmills designed by a millwright with scientific interests, Thomas Yeoman (c. 1708-81), who in 1752 erected a windmill to work Hales’s ventilators on the 20 gun “Sheerness” man of war. By June 1754 he had put up another to work those on Maidstone gaol, and by 1758 he had erected other windmills to work the ventilators of Bedford and Aylesbury gaols, and of St. George’s Hospital, London. In 1752 Hales installed ventilators in Newgate Prison, worked by a windmill on the leads. William Maitland recounted: The City has been so good lately as to introduce a Ventilator on the Top of Newgate, to expel the foul Air, and introduce fresh, to preserve the Prisoners Health; and the Prisoners are many of them kept in distant and more airy Prisons, till within a few Days before their Trials. Sweet Herbs also are strewed in the Court and the Passages to it, to prevent Infection; and the Snuffing up Vinegar, it is said, is the most likely Way to preserve the Healths of those that are obliged to attend such Trials. |

The ventilators

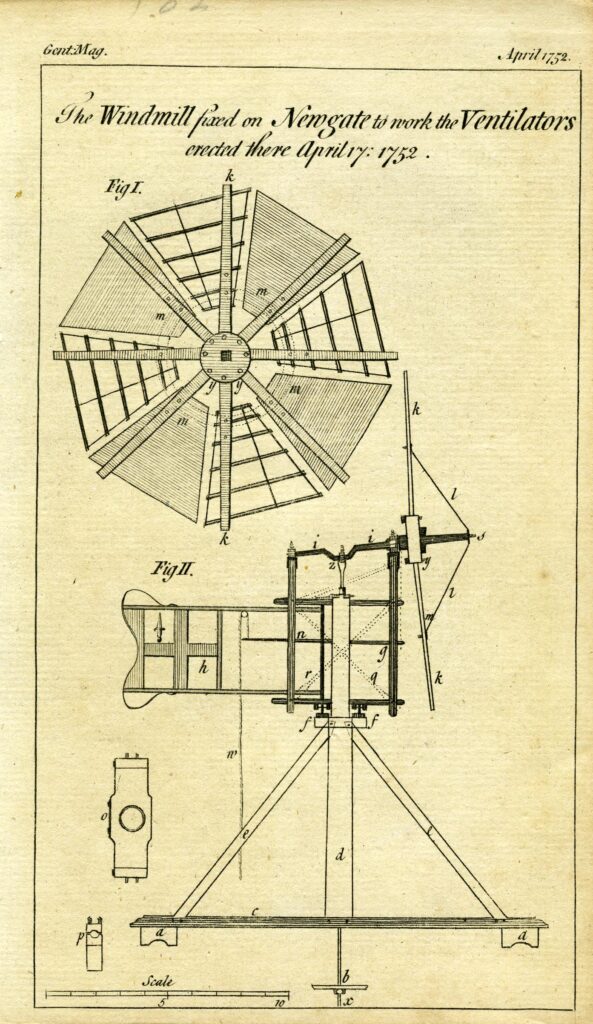

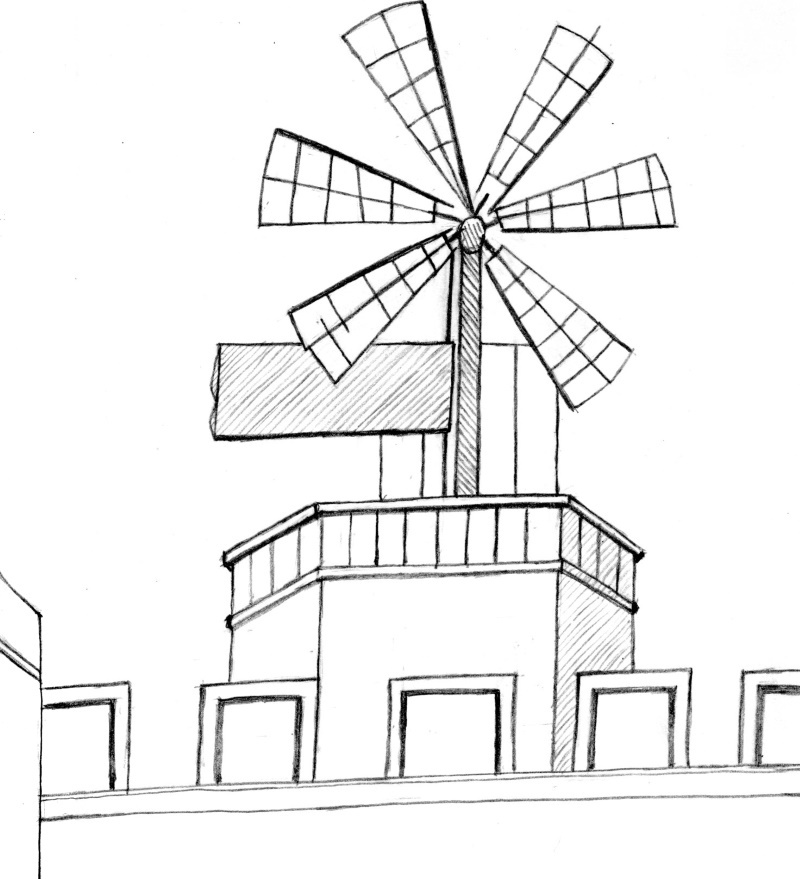

Immediately on their completion, ventilators and mill were well publicised by a description and two copperplates in the Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1752, pp.179-182. This was deliberate promotion by Hales of the “humane and laudable” example of the City of London, and he immediately sent copies to interested parties in France, Italy and Germany. The mill, wrote Hales in the Gentleman’s magazine, was “designed and contrived to move with a small degree of wind, and withal to obtain a sufficient power in a small compass.”

The ventilator itself comprised a very large box beneath the leads divided into four big compartments, two over two. Each compartment contained a large (wooden) “midriff” or diaphragm laid flat, hinged at one short end and moving up and down at the other. A system of one-way valves ensured that on each up stroke of the midriff, air was sucked in below it and expelled above it; on the down stroke, new air was sucked in above, and the air below was expelled. The valves were hinged with strips of tanned sheepskin, and in closing fell on strips of woollen cloth nailed round the valve holes, to break their fall and make them more airtight. The four midriffs were connected to both ends of a rocking lever, itself connected to the reciprocating rod from the windmill.

A single large exhaust duct vented the air above the leads, and the air was so foul that two workmen who breathed it instantly vomited so violently that they vomited blood. The branches from the extraction trunks to the rooms had manually controlled shutters or slides, so that the rooms could be ventilated in their turns.

“The Windmill fixed on Newgate to work the Ventilators erected there April 17: 1752” – engraving from the Gentleman’s Magazine

(Mills Archive Collection, MCFC-ENG-011)

The windmill

| The Newgate windmill was built by the Poplar millwright Cooper or Cowper. In June 1752, Hales wrote: As to the Windmill, it is a very good one, and so compleatly well made, with strong Iron Braces, and Brass Friction Wheels, or Castors, for the Frame to turn round on an Iron Plate, so as the more readily and easily to turn and face the Wind; that the Millwright complains, that it will be too hard a Bargain for him, if he is obliged to stand to his Agreement, to maintain and oil the Mill for three Years: He humbly prays therefore, that he may be released from that Part of his Agreement. Hales supported him in this, saying the millwright (i.e., Cowper) built the mill for 50 guineas, that another millwright who had asked him (Hales) £59 for an inferior mill would no doubt have asked £70 for this one. The mill for the “Sheerness” was made by Yeoman, who had recently told Hales in all seriousness that it had cost him £50 over the agreed price. And, Hales concluded: It was absolutely necessary to fix a Scaffold round the Mill, in order for a Man to stand upon, to furl or unfurl the Sails; this, the Millwright says, was not included in the Agreement to make the Mill for Fifty Guineas. The windmill plate in the Gentleman’s Magazine comprises scaled elevations which show the mill was tailvane winded and had a windwheel of eight broad paddle blades, 14½’ (4.42m) in diameter. The (wrought) iron sail axle is continued forward as a bowsprit, with eight bracing rods to the blades. The sail arms are wood, mortised into a solid wood hub. The sail frames differ quite a lot from 19th century fan blades, but like a fanwheel or a pumping windwheel, they will have a high starting torque, and so extract some air even in a light breeze. An iron reciprocating rod connects the throw crank of the iron sail axle with the rocking lever working the two pumping midriffs of the ventilator. On the face of it, the windwheel is far too solid to the wind, but the blades being open frames, cloth covered, experience would soon dictate how far to spread the cloth. The tailvane bears the City’s arms. The cross-trees rest on blocks at their ends through which they are firmly bolted down to the roof (this is essential as the mill is far too light to be stable on the trestle by its own weight). |

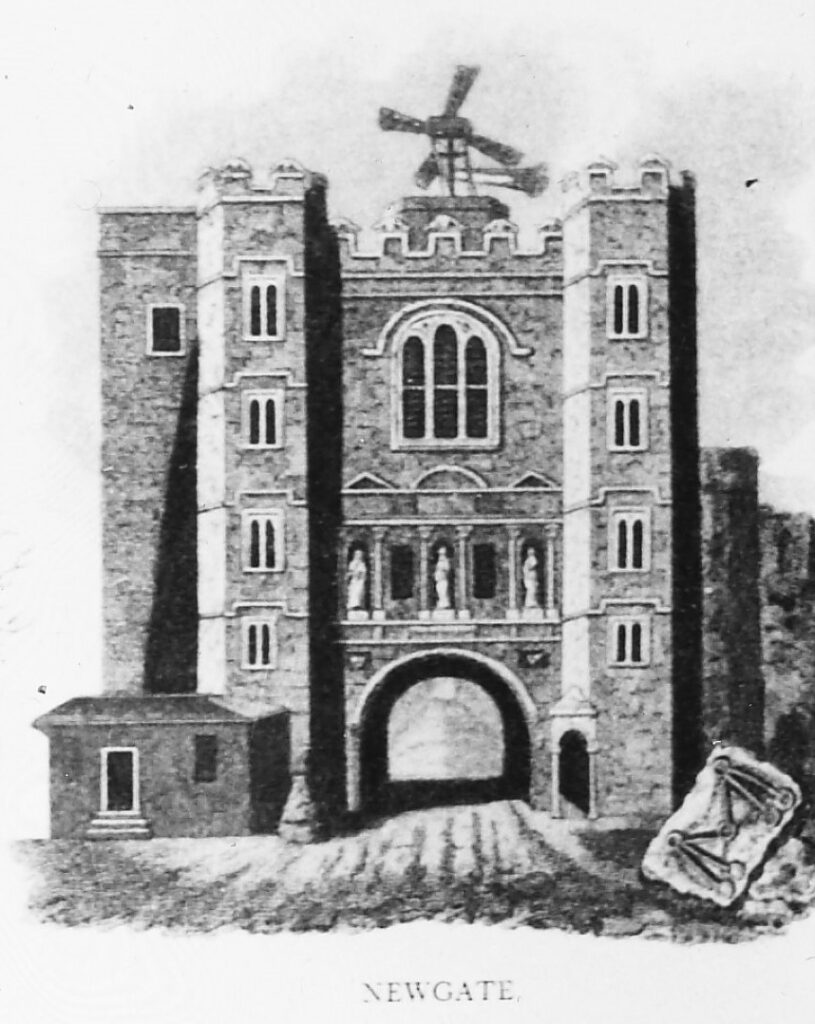

(Mills Archive Collection, JSPB-ODR-017)

| Two engravings of old Newgate crudely represent the mill as a detail. The first is the frontispiece to William Maitland’s History of London, (1756); the second is in Walter Harrison’s New history of London and Westminster (1775). In the latter it has a pent roof and four sails, in the former it has six sails, the sails in both are narrower than in 1752, but I would not read too much into any of this. Both show it placed over an hexagonal or octagonal “base” rising above the ornamental battlements, which must be the reefing stage erected by Cowper, and hiding the trestle. |

(Mills Archive Collection, JSPB-ODR-018)

The results of ventilation

| At Newgate, all the branching trunks to the twenty-four wards (rooms) were installed by October 1752, the air being sucked out of the wards in turn. In February 1753, Hales reported a great reduction in the mortality in the jail in the four month period October to January, compared with the same period of the previous six years, but ventilation by itself was a mere palliative to the conditions inside it. On 9 June 1752, Hales and two medical doctors, Gowin Knight (1713-72) and John Pringle (1707-82), went to Newgate and viewed the Ventilators worked by a Windmill, drawing, like large heavy Lungs, at the Rate of 7000 Tuns of foul Air per Hour, out of several Wards at the same Time, which were thereby sensibly sweetened, to the great Comfort of the Prisoners, who informed us with Pleasure, that they thereby enjoyed much the better Health. I think it will be very requisite to have the Mill go as much as it can every Day: And even in Winter to change the Air daily to such a Degree, as it shall be found the Prisoners can bear without Inconvenience. For foul Air long confined, will putrify in Winter, though not so soon as in Summer… The air, said Hales, does not have time to stagnate and putrefy, which takes many days, and it is this putrefaction, “which by being the most subtile Dissolvent in Nature” dissolves the blood and humours of our bodies, thereby producing gaol fever. In fact, typhus is caused by a micro-organism whose vector is the tiny body-louse of filthy clothing, but this was not discovered till the early 20th century. Therefore, other causes must explain the reduction in mortality. Perhaps it was the luck of a single short, four month period, or perhaps it was the effect of other changes which were proposed at that time, those of burning brimstone (which repels lice), and of cleaning the wards and scraping their walls. But in any event the wards stank, so the ventilation was welcomed. In June 1752, Hales wrote: It will be absolutely necessary to have a Man to furl and unfurl the Sails of the Mill, as Occasion shall require; and also to open and shut the sliding Shutters of the several Trunks, daily, that all the foul Wards may be refreshed in their Turns. It is probable that about eight or ten Wards may be aired at a Time. Although it appears that after some delay this suggestion was carried out, on 15 February 1755, Dr Pringle wrote: In passing by Newgate, from Time to Time, I am sorry to see the Machine so often standing still, though there seemed to be Wind enough to turn the Sails. I doubt the Effect of that Contrivance is in a great Measure lost, by there being no Person appointed to keep it in Order, to regulate the Sliders, and to turn the Sails to the Wind, when the Wind is too weak to perform that Action itself. But the Truth is, I despair of getting thoroughly the better of the Distemper and Contagion, without building a larger Prison, better aired… Repairs were made to the ventilators in 1758. By 1772 neglect had rendered them “totally useless”, but repairs were done in 1774. In November 1755, it was resolved to erect a new jail, which, after many delays, occurred between 1770 and 1780, when it was promptly burnt out in the Gordon Riots. The old Newgate was cleared away between 1776 and the 1780s. Hales’s ventilators were made mandatory in the Royal Navy by Admiralty decree in 1756, and by March 1752 they were in use in the vessels of the French East India Co, although it was claimed the continuous fatigue to the crew in working them was such that many ships had laid them aside. Nevertheless, Hales’s work is thought of sufficient importance for him to be counted one of the fathers of public health. |

Thank you to Amanda Knight, Andrew Ryan and Ann Grimmer who transcribed Stephen’s typescript through the Archive’s ‘Archiving at Home’ site.