Stephen Buckland

| George Packham was an English miller and millwright who made his name in France in the early 19th century. He became a friend of Louis-Philippe I, a king whose reign was destined to be short lived. This is an abridged version of an unpublished paper on Packham by Stephen Buckland (1935-2006), which is held in the Archive’s collections. | |

George Packham’s early life

| George Packham was born in Shortbridge township, Fletching parish, Sussex, 14 April 1792, one of the nine children of a miller. After school at Horsted Keynes, he was apprenticed for seven years to a Mr Sudds, millwright of Lewes. About the end of his apprenticeship he married, and, towards the end of the Napoleonic wars, he also took an old mill at Horsted Keynes. He spent a lot of money on improving it. The collapse in prices after 1815 probably ruined him; his improvements had left him in debt; so, he made over all his effects to his creditors, and moved to London as a journeymen in the old Society of Millwrights. Twelve months later, he and a fellow workman left to try their fortunes in France. They had not a word of French, “and when the two Englishmen required such a commodity as a fowl or a joint of mutton for dinner, they had to draw a picture of it” (Miller, 3 Sept 1877). They lodged at Eu (Seine-Maritime), a small town near the mouth of the Bresle, nineteen and a half miles from Dieppe. The château of Eu was inherited by the Duke of Orleans on the death of his mother in June 1821. From 1830 to 1848, he was Louis Philippe, King of the French. He paid his first visit to the château since 1791 in late August 1821, found it in a very bad state of repair, and thereafter spent vast sums on it and its estate; it became and remained a favourite residence of his. In the 1820s he was keeping a low profile politically and was engaged in consolidating his family fortunes. Therefore, he did not neglect the industry and commerce of the district, | |

and he was engaged in the utilisation of the local water power for industrial purposes with very little prospect of success. Having time on his hands, and being naturally interested in everything connected with mill work, our English millwright was standing one day watching the proceedings of the French workmen.

| And while he was making unflattering criticisms of their work, an English voice asked him, “Could you do it in a better style?” Though much surprised, Packham at once replied “Yes”. The questioner was the Duke’s English valet, a Mr White, who will appear again below. An interview with the Duke (who had fluent English) ensued, who “was so impressed with the straightforward replies and practical good sense of the stranger that he at once entrusted him with the superintendence of the work.” On the mill’s completion, the Duke asked Packham to become its tenant. Packham said he would like to, but had no capital, whereupon the Duke lent him 30,000 francs without asking any security. |

| That is the Miller‘s account. Louis-Philippe’s architect, P F L Fontaine (1762-1853), in c 1845, gave a somewhat different version: There were two estate watermills near the castle, on the main current of the river Bresle. |

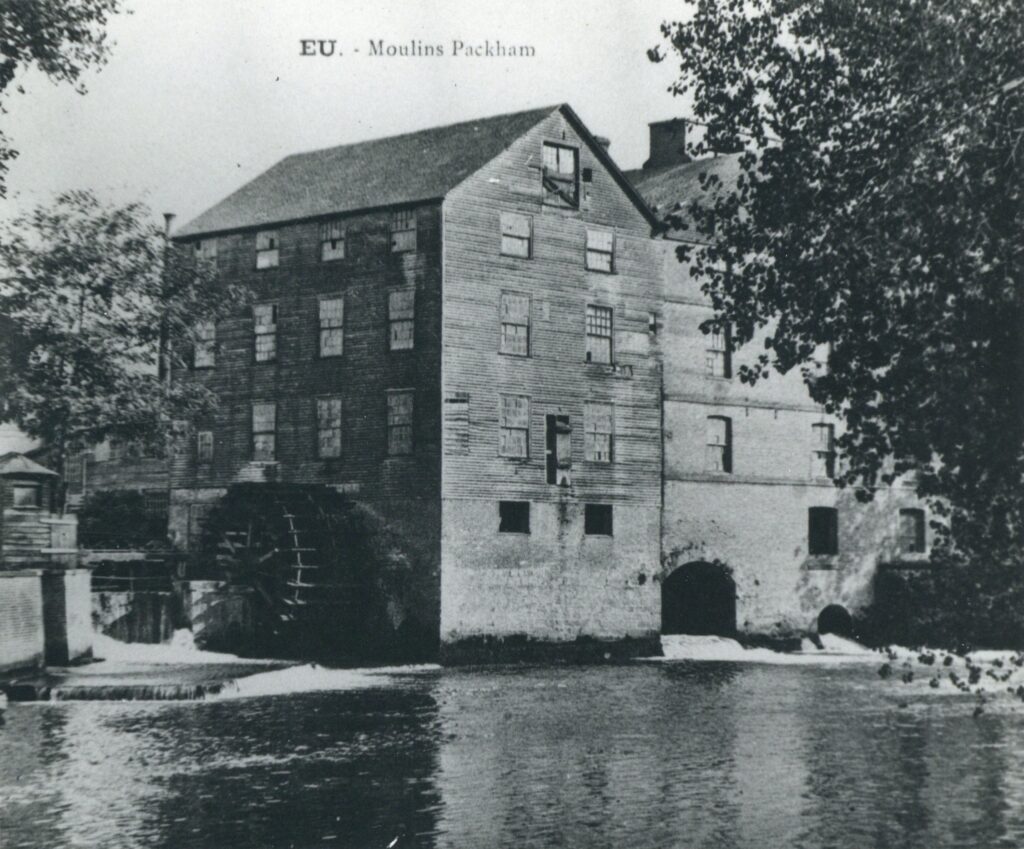

They scarcely brought in the sum of two thousand five hundred francs, were in the worst possible state of construction, and would perhaps have been allowed to crumble into ruins, when an English mechanic, a plain workman, a practical and very experienced man, having realised the advantages of the site, and also the state of things, took a lease of that one of the two mills that the former lessee had given up, and fitted it up on a new system of mechanics. The prompt success, of which his talents and probity formed the basis, soon enabled the undertaker to lease the second mill, and put him within reach of creating, in an excellent position, before the eyes of the Prince, one of the finest and most remarkable works in the département. Nowadays the Packham mills, for one must call them by the name of their author, are renowned throughout Lower Normandy, where they have already served as patterns for several other mills.

| The establishment which rapidly sprang up under Packham ground corn, baked ships’ biscuits, pressed oil seed, and sawed and planed planks. The original capital loan was repaid; within ten years of his arrival, his creditors at Horsted Keynes were paid back in full; the rent for the Eu works rose from £60/year to £1710 in 1841; and the last enlargements under Packham were completed in 1846. He was a successful man (we hear no more of his fellow workmen). Before 1848, he had retired from the management of the works, and he seems to have lived both at Eu and at Brighton. |

The Moulins Packham

| In 1836, the Moulins Packham occupied several acres. They comprised a large mill building, four floors high to the eaves, with three waterwheels. Two of these drove three pairs of millstones each; the third drove a layshaft which passed under the roadway to a much lower saw mill building on the other side of the road. On another part of the site was a long oil mill building. In the middle Packham had a quite modest house with a large garden. George Packham previously can have been no more than a journeyman millwright, but was clearly no ordinary one; and it speaks volumes for his talents, and perhaps shows too what he had learnt of the most advanced practice during his year in London, that he was able to turn master millwright and design and build such major plants. He is one of a number of technically trained Englishmen who made their careers in France after 1815. He may be too, Fontaine’s “English engineer” who built the château’s waterwheel worked pump house, clearly shown in Fontaine’s drawing of 1836, and in the site plans. |

| Between 1840 and 1845 the works were expanded further. The saw mill was moved and the oil mill extended, bake ovens were installed in the old saw mill building and there were now twelve pairs of millstones, as well as a large timber yard. In 1845 a works railway (man or horse hauled), running close to Packham’s house across its garden, and complete with one-truck turntables, took trucks between the oil mill to three loading/unloading points on the Bresle basin on the downstream side of the corn mill. The straightened course (“the new canal”) of the Bresle leads straight to the port of Le Tréport, two or three kilometres off. An account of Eu published in 1839, refers to “the encouragement accorded industry by the establishment of the two Packham mills, so called from the name of the skilful English mechanic who invented them.” A footnote adds: |

Mills, one of which supplies to the building industry an immense quantity of planks sawn with marvelous rapidity, with the help of a new apparatus, whilst the other delivers annually for the food supply nearly a million Francs worth of flour, and to the marine the most excellent biscuits.

| Fontaine in c 1845 said that the mills’ prosperity was assured by the help and encouragement of Louis-Philippe, who had, |

right from the beginning, wished to take part in the success of he who was able, in an undertaking of this sort, by his conduct and industry, to merit his confidence. Thus it is that Packham was entrusted with the execution of the magnificent marquetry-work parquet floors of all the rooms of the château, and with yet other works. Thus it is that, always master of his manufactury, free to manage its progress as he willed, this skilful mechanic has, on every occasion, obtained the assistance and the funds necessary for the amelioration and improvement of the different parts of his enterprise.

| In 1844, yet another writer, in an extremely high-flown passage, says much the same of the king’s patronage of “M. Georges Packam”. He refers to the oilseed crushing edge runners; and says the works were making barracks of huts (baraques) to serve as tents for the French colonising troops in Algeria. And tells us, what we did not otherwise know, that the mills employed English mechanics. |

Revolution

| In February 1848, revolution broke out in Paris, at a time when Packham was engaged in putting up machinery for new waterworks at La Ferté-Vidame (Eure-et-Loir), a château of the Orleans family. He went to Paris to see the king about it, |

on the day that the famous Reform Banquet was to have taken place. Mr. Packham called at the Tuileries, scarcely expecting to see the king, who, however, saw him in his breakfast-room, and expressed his belief to his visitor that they would be able to cope with the Revolution.

Image from Gallica via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaspard_Gobaut,_Le_palais_et_le_jardin_des_Tuileries,_1847_%28cropped%29.jpg

| Louis-Philippe said to him, “Don’t be uneasy, Packham, don’t be afraid of a revolution, we have 80,000 National Guards inside the barrier, and plenty of troops outside.” |

The Duc de Nemours and several generals coming in, Mr. Packham left, His majesty saying, “I hope I shall see you, Packham, at Ville d’Eu by the end of the week, when we shall have a better opportunity of talking about these things.” On leaving the palace Mr. Packham saw the mob tearing up the pavement and erecting barricades in the Champs Elysees. The Revolution had broken out, and it was with some difficulty Mr Packham, three days afterwards, succeeded in getting out of Paris and crossing over to England where, on the second day after his arrival in Brighton, he received a mounted messenger from Louis-Philippe requesting him to come immediately to His Majesty at Newhaven. (Miller, 3 Sept 1877)

| The Times account, datelined Newhaven, 3 March, which their reporter had from Packham himself, says that he was a long-standing protégé of the king’s, and was with him “on the memorable Tuesday appointed for the Reform Banquet up to within an hour of the outbreak of the revolution.” The king and his queen fled to England aboard an English steamboat, which disembarked him at Newhaven on the morning of 3 March, where they put up at the Bridge Inn. William Catt of the Bishopstone tide mills was one of the first to greet him there, and offered to put him up at his own house, but this was declined. The king then enquired of Packham, continued The Times and learning he was at Brighton, “expressed a desire to see him immediately.” On a messenger reaching him there, Packham “immediately posted to Newhaven with a gentleman named White, who had been in the household of Louis-Philippe many years.” |

| A self-appointed deputation from Brighton went to greet the king, travelling by a special afternoon train; Packham, though not part of it, acted as master of ceremonies. “Gentlemen from Brighton, I presume,” said the king with his usual frankness, in the purest English. “Oui, oui your Majesty,” was their reply in French and the vernacular, a long-standing joke against them. Howarth’s biography does not mention this incident, but says Louis-Philippe was subjected to addresses in Latin and French by the pupils of the Lewes free grammar school. Later the same day, The Times’s correspondent was introduced by Packham to the king, who was reading an English paper between receiving guests. Packham too, offered to put up the royal couple in his Brighton house. The king again said no, but before they parted, gave Packham all his money to change into English coin, and to buy him clothes, “of which,” he said smiling, “I am very short.” (This was later embroidered into a tale that he had had to borrow a suit of clothes from Packham). Packham, and White, the king’s valet then returned to Brighton by post chaise. The Journal du Havre, 5 March 1848, notes that the king was seen by “M Packham, well-known at Dieppe and Eu, and whom he had caused to come from Brighton”. |

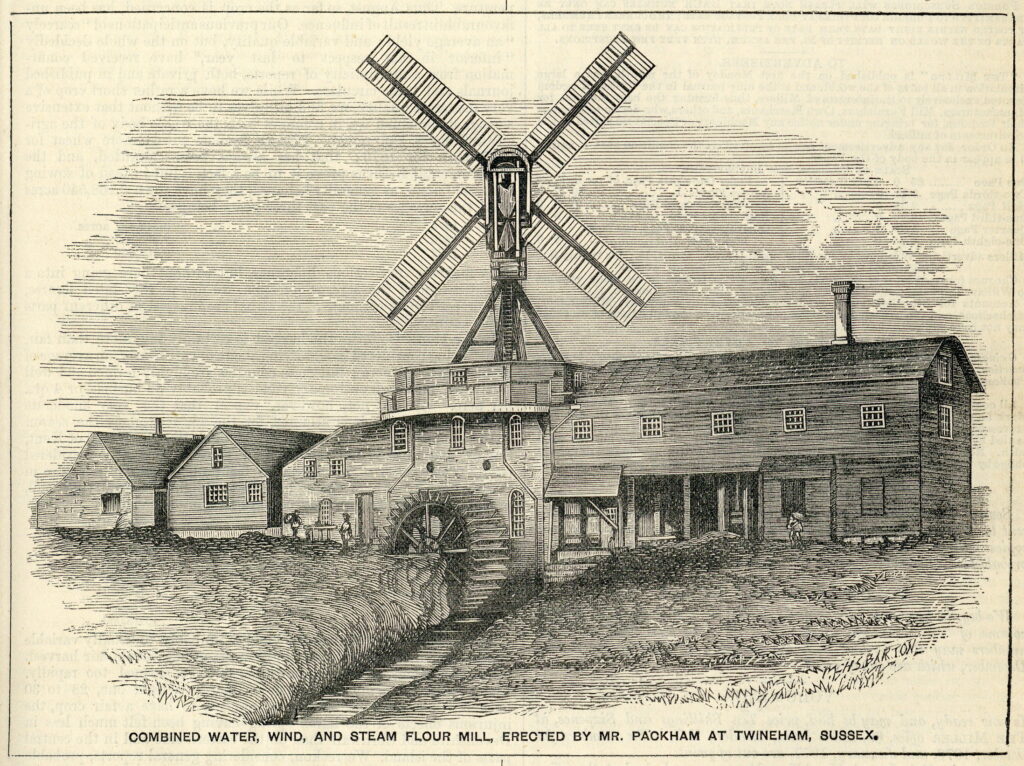

Twineham Mills

| Packham retired to his English home from at least 1843, 1 St. George’s Place, Brighton, where he lived till his death. He designed the unusual Twineham windmill during this time, for his son-in-law John Wood Esq., the principal landowner of the parish and later lord of the manor. It was a wind, water and steam mill, very similar to the West Ashling mill of c 1859 which may have used the same castings. In his retirement Packham stayed fit and active, and did not, claims the Miller, look his age. He died at his Brighton address on 20 September 1872, aged 80, and was buried in Keymer churchyard. |

| Thank you to Andrew Ryan, Anne Harrison, Ann Grimmer and Guy Boocock who transcribed Stephen’s typescript through the Archive’s ‘Archiving at Home’ site. You can read the full transcription here: https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/george-packham-miller-and-millwright-1792-1872-unpublished. Please get in touch if you would like to help transcribe documents from our collections. |