| John Munnings (1916-1987) was the nephew of the famous artist Sir Alfred Munnings (1878-1959), and like his uncle before him he was born and raised at Mendham Mill, Suffolk, where his father was the miller. |

(Mills Archive Collection, DOLM-1123588)

| Munnings fought in the Second World War and was held prisoner by the Japanese. After the war he married and became manager of an agricultural firm. He was a keen artist, giving exhibitions at the Assembly Rooms, Norwich, and combined this with his interest in milling to produce many sketches of watermills. In June 2013 the Mills Archive was given his sketches and the draft for his book “Watermills and their millers”, written in 1972. The book opens with Munnings’ reminiscences about growing up at the mill. |

Early days

| In common with most miller’s sons, I began to learn about mills at a very early age. The first great lesson for a miller to learn was the use of the faculties given to us by nature, firstly one’s eyes to watch, amongst other things, the flow of the river in the millstream. The river was full of natural beauties such as water-lilies, flowering rushes, crowfoot, arrowheads, and sundry riverbank flowers; overhanging trees with their branches tipping the water; swallows, swifts, kingfishers, mayflies and dragonflies; not forgetting the stately herons, the swans, ducks, and moorhens. Apart from all of this, however, observing flow of water was essential so as to the make the utmost use of the power available – this of course being late Spring, Summer and Autumn, when the river’s flow was gentle and controllable, unlike the yellow uncontrollable monster in times of flood. One cannot help but remember that when the millers controlled the flow of their rivers, there was much less flooding. In those days when there were few metalled roads and less concrete, it took so much longer for a river to flood. Generally, after heavy and continuous rain in the upper Waveney Valley in the Diss area, a notorious spot where the thunderstorms coming from the west generally split up – one coming down the Norfolk side of the valley, the other from the Suffolk side, and joining up again at Bungay or Beccles – it was nearly 24 hours until we at Mendham Mill had to draw the flood gates or take the flash board off the weir. Doing this at the right time would help to keep the water moving, thus saving the wheel churning water, or backwatering as it was generally called, but this was part of a miller’s life, and was as most things done by instinct. Many a time I remember my father saying to me, “Boy, how long has it been raining?” Then after receiving my answer, and remaining silent in thought for a few seconds, he would say, “Go and draw one gate up about a foot, or perhaps take the flash board off,” – a dreaded job, not so much due to the power of strength it took to lift the board off the securing pin and ledge against the weight of water, but because the attached chain used for replacing this had a nasty habit of getting round one’s foot. One dark night this pulled me into the river. Next in importance was one’s ears, as the only rev-counter available was one’s finger on a shaft and a watch. To get efficiency and high quality of grinding, the correct speed of machinery was essential. When grinding with millstones one had the familiar clatter of the shaker shoe on the damsel for the correct speed, and the particular whurring sound of the millstones rubbing together. There was also the familiar sound of the water hitting the buckets of the wheel, and the low rumble of the gears in the cogpit in a well-balanced mill. In fact, every machine had its own particular sound when running correctly. This also applied to the wheat cleaners and cockle cylinders, as well as to roller plants – the hum of the roller mills, the purifiers, centrifugals and scalpers, each having their own indescribable noise when running correctly, all adding to the music of the mill. Added to this were the snapping and cracking of the driving belts, or perhaps an odd belt fastener catching on a floor joist when driving through a floor. Many a generation of millers whose abode adjoined the mill would sleep peacefully to the music of the mill, soon awakening by instinct should anything happen. The nose was no less an important factor – few things were ever sweeter than the smell of freshly ground meal, but one could always detect above this the smell of an overheated bearing, when there would be a rush for the castor-oil can. This, though little known, was the cure for overheated bearings; mutton fat and graphite being used for large bearings of the waterwheel shaft, upright shaft and millstone boxes. The thumb and forefinger were generally used for testing meal, and before the days of moisture testers the quality of the grain was decided by chewing a mouthful. This, for the experienced miller, was as accurate as any modern equipment. It had to be. |

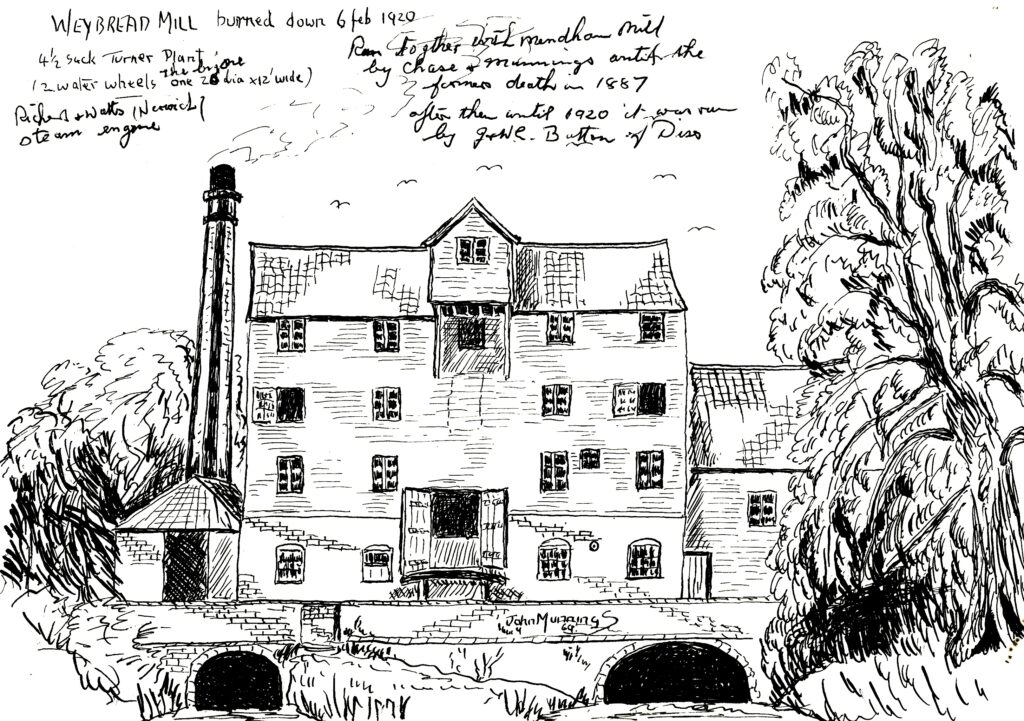

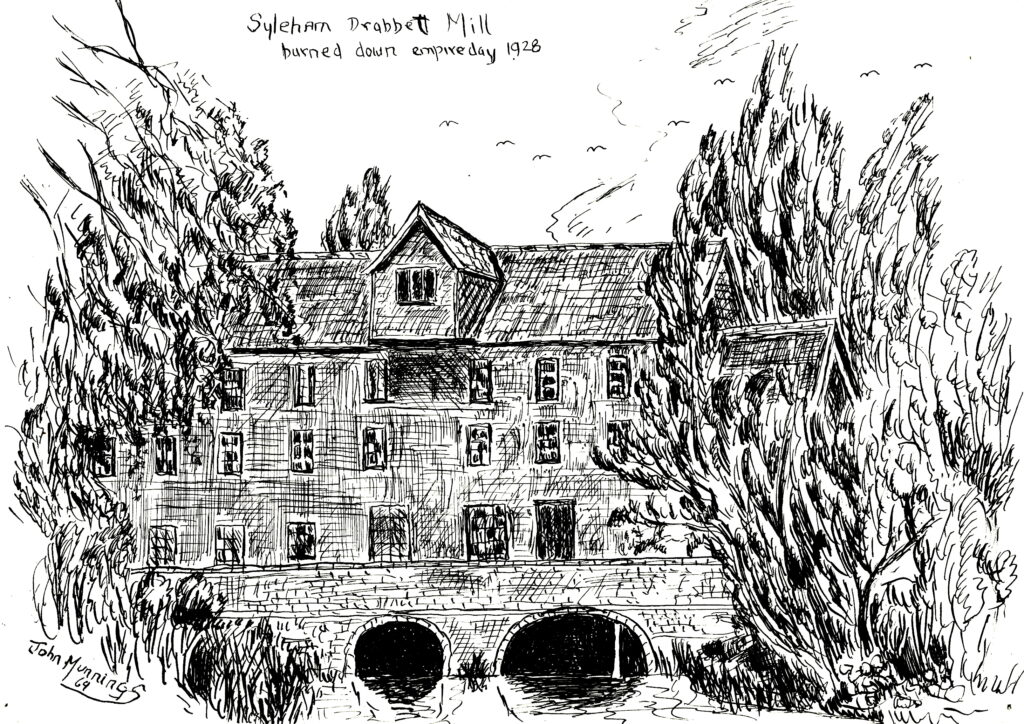

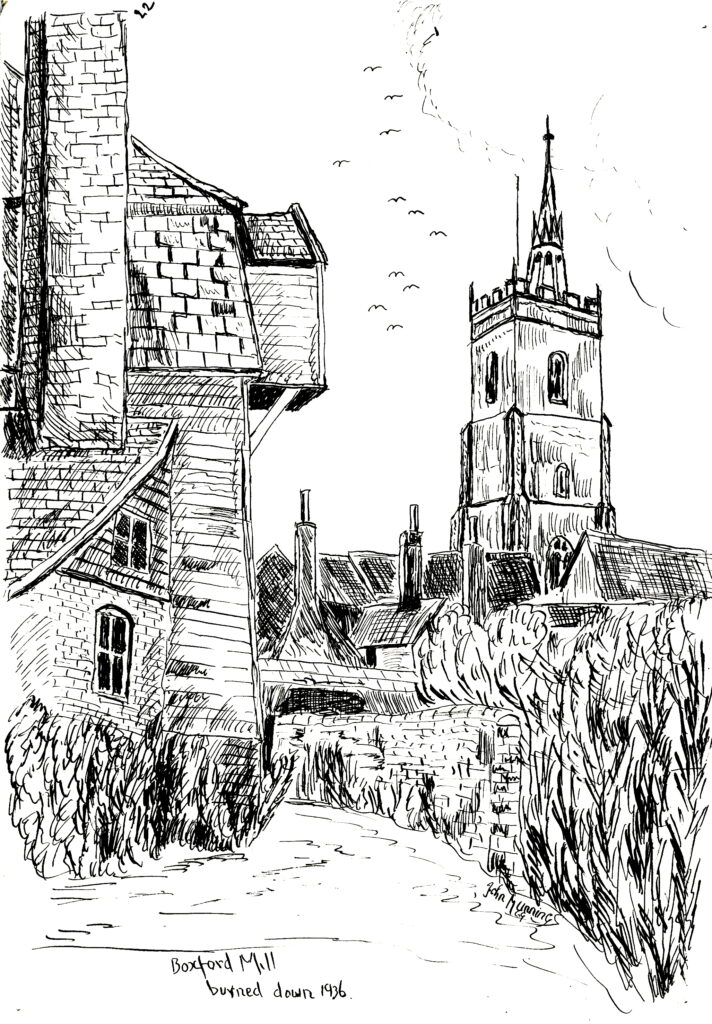

| Before the smell of hot bearings leaves me, I am reminded that this was one of the causes of mills being destroyed by fire. So many picturesque mills seem to have succumbed to this fate over the ages, especially in the days when suction gas and diesel engines were used as auxiliary power. In those days there was little or no profit in the business, owing to the competition of larger mills, so one had to get every ounce of power out of everything. Hence, many of the engines were overloaded. Generally, if you needed an extra 50 horsepower, you obtained a 40 horsepower engine and opened up the governors. This would go unnoticed, unless at night when the exhaust pipe would be red hot and belching sparks. This was the cause of the fire which destroyed Costessey Mill near Norwich, July 1924, as related to me by the late C. A. Thompson, a well-known millwright, who was working in the mill at the time. Wooden pulleys were used extensively in the 1920’s and these would sometimes slip on the shaft, causing friction and catching fire. I remember this once happening, fortunately, I was able to stop the mill in time. Other causes are best not mentioned, they are being only hearsay. Unfortunately, only a very few mills were rebuilt. On the Waveney there was fine mill at Weybread destroyed in 1920. I remember that night seeing a massive red glow in the sky, and father coming in saying, “Weybread mill is on fire,” and some days later seeing burnt timber floating down the river. One of the most picturesque, Syleham drabbet mill was burnt on Empire Day 1928. Others that come to mind being Boxford 1936, Cringleford 1916, Chapel Mill Gressenhall 1914, Great Ryburgh 1919, Horstead 1963, Topsfield Mill Hadleigh 1952, Newbridge Mill, West Bergholt 1960, Dedham 1908 (rebuilt), Wormingford 1923, Raydon 1916, Great Blakenham 1916, City Mill Canterbury 1935, West Mill Newbury 1961, Granchester Mill 1928, one could go on and on. Then there was a recent case of a film company burning down Hardingham Mill in the making of the film “The Shuttered Room” [1967]. One can think of nothing more callous in this day and age. | |

A dying trade

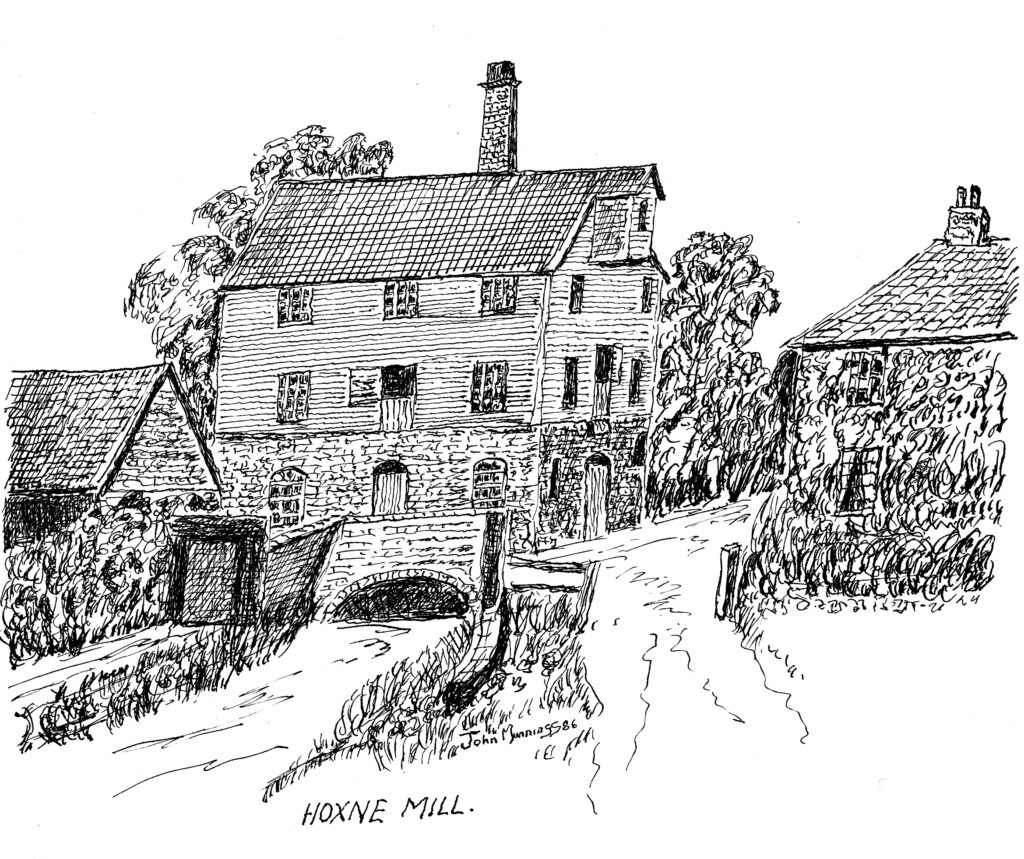

| The first death knell of the watermill was sounded at the latter end of the 18th century, with the introduction of the steam engine. The first use of these monsters, as they were termed, was to pump water from the tailrace to the head of the mill, so as to give a greater volume of water to the mill, but when steam engines became rotative after William Murdock’s invention of the Sun and Planet gearing in 1782, the country went steam mill mad. Some mills where the waterpower was small installed a steam engine. It was at this period in the early 19th century that some of the mills started going out of business. Others prospered especially in the 1850s, but the great agricultural depression of the 1880s sent a lot more out of business. I can well remember my grandmother telling me how they used to take bran away from the mill and burn it, as nobody wanted it even as a gift. At this time roller plants were introduced by some country millers as a means of keeping in business, but a number of mills had to fall from their high status of making flour to the grinding of dredge corn, etc. for animal feed, “or dirty milling” as I once heard an old flour miller say. It does not seem many years ago that there were at least 15 mills in the Waveney Valley, with rollerplants, seven of them being water mills: Hoxne had a Tattersall midget plant; Weybread had a 4 1/2 sack per hr. Turner plant; Mendham had a 3 sack Turner plant; Limbourne Mill, Homersfield, had a Tattersall midget plant and Earsham, Bungay and Ellingham all had Turner plants. | |

| A lot of flour was shipped by wherry from Bungay Stathe to Yarmouth, then transhipped to London and Newcastle. Coal was generally unloaded from the wherries here and taken on the return journey for use in the mill engines, the price then being about 18/6 d. per ton ex-wherry. There was also the Waveney Valley railway, now gone and forgotten, which linked the main Norwich – Ipswich line at Tivetshall with the Ipswich – Lowestoft main line at Beccles. In the days of the great old Eastern Railway this line was busy and efficient. I have often heard father say that if he contacted the Station Master at Homersfield about 8am in the morning and ordered one or two box-wagons, all the Station master did was to telegraph Stratford (the old G.E.R. Headquarters) and the wagons would arrive by the mid-afternoon goods train. They were then loaded with flour and were picked up by the 7.40 goods train and would arrive in London early next morning. It makes one wonder how long it would take today. |

Harvest time

| Looking back, the most wonderful time of the year in those days was harvest time, when the marshes round the mills were alive with farmers and their men cutting the marsh hay. One could hear the clatter of the horse-drawn clippers and the rattle of the dragrakes and as one looked up or down the valley there was row upon row of haycocks. This marsh hay always came the same time as the corn harvest, and it makes one wonder to-day, especially in these days of mechanisation, how they ever got through all that work. But somehow the corn and hay were always got in better than it is today. A fair amount of wheat was thrashed out in the field, as most farmers were glad to start seeing a return for their year’s work, and as a boy I can remember seeing wagons and tumbrels laden with wheat, queueing up for nearly quarter of a mile, as apart from harvest, carting wheat to the mills was one of the most important times on the farm. From the larger farms and estates especially came the massive Suffolk horses all dressed up with their brasses, their manes and trails braided and tied with coloured ribbons, sometimes four horses to a wagon. As they drew up to the mills, the trace horses were uncoupled, the miller would bring out a sample of the wheat he had bought at the local market, and check every sack on each wagon. And heaven help anyone if there was any variation. I often wonder what any old miller would say if offered a sample of today’s wheat direct from the combine harvester. An old farmer I was talking to a few months back told me as a boy he always liked to bring wheat to Mendham Mill, as my grandfather always gave him 6d. “conscience money,” I believe he always said. Once at the age of 14 he left his father’s farm at Cratfield, about ten miles away at 4am in the morning with a load of wheat. As it was raining hard he had to sheet up his load in the dark. On arrival at the mill, my grandfather rebuked him for coming on a wet day, saying his load must have got wet. Anyhow when the wheat was checked and found to be dry, he was forgiven. Hence the 6d. | |

| At these times, a miller’s office was always overflowing with samples of wheat which was generally bought at a local market – rarely on a farm, as farmers in those days were expected to bring their sample of corn to the local market. Wheats generally grown in those days were yeoman, little Joss or squarehead master, these were good red wheats, and almost as good for milling as the imported Manitoba wheat, or as that almost forgotten which used to come from Rumania and Manchuria. | |

The Corn Exchange

| Often now when walking down Exchange St. Norwich, I look back on the days when the busy corn exchange stood, there, the site now occupied by extensions to a great store. I remember how I used to like going there as a boy with my father, a great palatial lofty building, full of stands occupied by millers, merchants and allied trades, mostly local but also grain importers from London and Ipswich. I remember the noise of all the talking and the rattle of the corn on the floor, as samples were tested, and also the odd pigeon flying around waiting to feed. It was a real place for what I term as “tales of millers told” – if there were only tape recorders in those days! When young one always looked forward to the last Saturday before Christmas, when the older members finished their business early. Then the fireworks started, generally saved up from the previous Guy Fawkes Day, and the sample bags of corn and meal started flying through the air, sometimes accompanied by slabs of linseed or cotton cake. What a terrible mess we used to get in, especially on a wet day! One seldom thought of the poor cleaners, but somehow the place was always clean for the next market. It was certainly a place of heart-breaking bargains, but in those days a deal was a deal. People would honour their word. The main thing was to be lucky enough to buy at the right time and in sufficient quantities, as one had to be satisfied with roughly 5/-d. per ton gross profit. I have known many a ton of flaked maize sold to farmers at little more than cost price, provided the 20 bags, then worth about 3d. each, were returned when emptied. There were times when imported grain was a few shillings a ton less at Avonmouth (owing to low dock charges) than Ipswich, then it paid one to send a lorry there instead of to Ipswich Docks. |

| Unfortunately, most of the old millers of that decade have now passed on. Several years ago, I was waiting on a corner of exchange Street in Norwich, when an old retired miller and farmer whom I had known long ago, came by. Eventually the conversation got round to the old market days, when he related to me how 60 years before, he was standing with his father in almost the same spot, not far from the ornate steps of the corn exchange. At the top of these steps stood a miller from a town not far away, a short man who always wore a high top hat to make himself look taller, and who had just been made Mayor of this particular town. When my grandfather, who was of the jovial showman type, went up to him he brought his hand down on the tall top hat and said, in a voice that could have been heard for miles, “Well I am dammed, you have been an old hoss all your life, now you are a Mayor”. Millers like blacksmiths were generally of independent nature, the older generation spending their days amongst peace and plenty, but one should not forget their importance in the country. The picturesque mills where their placid lives were passed, these memorials of a busy past, may here and there attract the eye, or absorb for a moment the attention of a few. But beyond such silent recognitions of a once flourishing industry, thus quietly but surely passing away, the change seems to progress to its close, unnoticed unless by those who may suffer by it. |