Elizabeth Trout

| This article was originally published in our blog on 31 October 2019. Last week, Tom, one of our dedicated volunteers, found amongst the press cuttings, a piece of card upon which were written a few scrappy handwritten notes. He saw the word ‘mill’ and a date of 1549. Knowing that I like a mystery, he gave it to me to decipher. The note says: |

Finsbury Field

2 mills, was 3

1549

Bones from the charnel house

By Regus Wolfe

Overland with dray

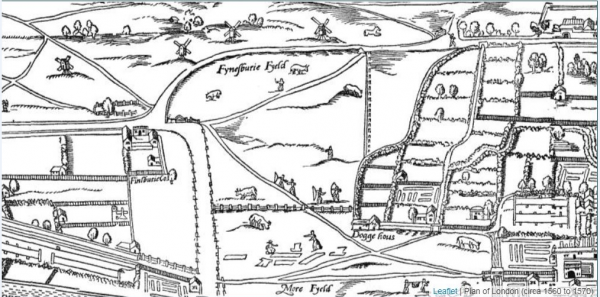

| How intriguing. So, I turned to Farries and Mason’s book on the Windmills of Surrey and London. Here is the story that they recount: A little to the east of Mountmill, in Moorfields or Finsbury Fields, a group of six windmills stood in the seventeenth century on a mound of macabre composition. In 1549 over a thousand cartloads of human bones from St Paul’s charnel house were dumped in Upper Moorfields, and the resulting pile, covered by rubbish and ‘soilage’ from the city, became a laystall, and – according to Stow – shortly afterwards the site of three windmills. The map of Aggas indeed shows three mills, while those of Faithorne (1658), De Wit (1666) and Ben Gerlen (1660) all show six. It is probably one of these mills that is represented on a rare panoramic view of London c. 1600 taken from the north, giving us our only sight of the Curtain Theatre of Shakespeare’s day which stood in Shoreditch. The windmill seen in the foreground is a post mill with open substructure, and its fellows were probably suppressed to avoid restricting the view. The Finsbury millers were at some pains to secure a free flow of wind: in the Court of Common Pleas it was adjudged that a house ‘built so tall that it stopped the wind to the windmills’ should be pulled down. The last of the ‘Fensbury’ windmills – on Windmill Hill – was pulled down in about 1750 to make way for St Luke’s Hospital, intended by Sir Thomas Ladbroke and other philanthropists to ease the lot of the poor and insane. ‘Mill Hill’ and ‘Windmill Row’ formerly lay near Finsbury Square. Well, that is a fascinating and slightly spooky story – I wonder if the mills were haunted? However, there is the name ‘Regus Wolfe’ in the original note. Who is he and how does he fit into the story? This required a bit of digging and this is another truly remarkable story. Putting my sleuthing hat on to research the environs of Finsbury and St Paul’s Cathedral c 1549, I came across the Survey of London written by the eminent John Stow in 1598. He also recounts this story but adds more detail and identifies Regus Wolfe. |

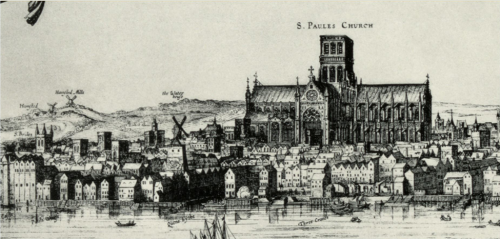

| The charnel house, belonging to St Paul’s Cathedral church (the old one before it burnt down in the Great Fire), was in the grounds of the churchyard. St Paul’s was an area where stationers lived and others dwelling around the churchyard and in Paternoster Row. From 1282, the area around the outside of the church walls was developed to provide shops whose tenants paid rent of church of St Paul to build a chapel to the Blessed Virgin Mary over the charnel house and to provide a chaplain. Several mayors from medieval times and other notables were buried in the chapel with elaborate tombs. However, following the Dissolution, the tombs inside the chapel were demolished. The bones from the charnel were removed to Finsbury Field, amounting to more than one thousand cartloads, paid for by Reign Wolfe. One can only imagine the sight of carts piled with bones being hauled by oxen out of London to Finsbury Field Vischer’s panorama 1616, the drawing above, shows the area around St Paul’s. | |

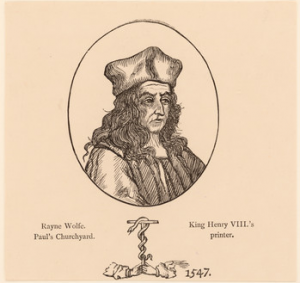

According to the Dictionary of National Biography, Reigne or Reyner Wolfe was a printer and publisher from Strasbourg. He became involved in the Protestant movement and developed contacts at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Wolfe acted as an agent bearing letters from Cromwell and Cranmer to English agents and protestant reformers in Europe.

| Wolfe came to England in about 1537, apparently at the invitation of Archbishop Cranmer and purchased the charnel house in St Paul’s churchyard from the Crown. |

After disposing of the bones, the chapel and charnel were converted into dwellings, warehouses and sheds for the stationer who lived in the area. Wolfe established a printing press, adopting the imprint and sign of the ‘Brazen Serpent’.

| Wolfe prospered and became the Royal Printer under Edward VI and held a patent as printer to the King in Latin, Hebrew and Greek. It also declared him to be His Majesty’s Stationer with an annuity of 26s 8d. Despite his protestant zeal, he was named in the original charter given by King Philip and Queen Mary to the Stationers’ Company in 1554. He was active in the company and made substantial gifts to it. When Queen Elizabeth confirmed the charter in 1559, Reigne Wolfe was described as Master of the Stationers’ Company, serving in that office three times. He died in 1573 and was buried in the church of St Faith which was a former chapel within St Paul’s Cathedral. |

| So where were the mills built on the bones of the charnel house? Going back to Farries and Mason, they refer to several maps of London which featured the mills. The Agas map of London c 1561 shows three mills on small hillocks on ‘Fynesburie Fyeld’ (as mentioned on the notes that Tom gave me). Later 17th century maps showed six mills. So next time you are in the vicinity of Finsbury Square, take a moment to consider what is beneath your feet – bones delivered by a Wolfe on which to build three mills. |