| Millwrighting has been on the Heritage Craft Association Red List of Endangered Crafts since 2019. Without increased opportunities and interest for millwrighting in Britain, the number of mills will slowly decline. To bring the craft into the public eye and highlight its importance in the preservation of our milling heritage, we have put together an online exhibition about millwrighting, which can be viewed here: https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/millwrighting/ Some highlights from the exhibition: |

The development of millwrighting

The word millwright did not originate until around the 15th century when the words ‘mill’ and ‘wright’, meaning worker, were combined to describe those who worked on mills. Until this point, millwork had been completed by the carpenter and the two skills shared similar traits, to such a degree that the phrase ‘carpenter’ was synonymous with ‘millwright’.

In this pre-industrial period, mills were mainly built of timber, though there were wind tower mills that were built out of stone where it was readily available. The first type of mill recorded in Britain was the watermill. Watermills had been in use in Roman times, and many are listed in the Domesday Book of 1086. These mills were similar in structure to houses, but containing milling machinery including millstones. A watermill was listed in Mapledurham, Berkshire in the book of 1086. There is still a watermill there today, however it is a rebuild of a mill that stood there in the 15th-century, with the oldest timber used in the mill dating from 1646. To power a watermill the millwright originally constructed a horizontal waterwheel that would directly power the millstones. This later developed into the vertical waterwheel, which would turn the pit wheel and power the millstones. The waterwheel would be designed to suit the water supply, usually following an undershot or overshot type. This is what we see today. In all, the millwright needed a significant amount of craftsmanship to construct a watermill in this period.

Read more about the development of millwrighting here:

https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/millwrighting/#content1

The waterwheel at Mapledurham watermill. The mill has existed since the 15th century.

Photo by Arthur Lowe

(Mills Archive Collection, LOWE-1036)

The millwright’s materials

| The millwright’s original choice of material for the building of traditional wind and watermills was wood. Wood has featured in the construction of mills since they were first recorded and it still features as an important material in millwrighting today, especially in the repair process. The choice of wood for the main parts of a mill was very important, and these may also differ depending on the type of mill. The wood would always have to be durable as it would need to last a significant amount of time. In addition the millwright would need to know the ‘needs’ of the mill, as mills can be compared to living entities in the way that they adapt to weather conditions by swelling and shrinking. Therefore, the use of wood in the building or repair of a mill would need a carefully considered approach by the millwright. The traditional millwright would in most cases use English oak when building or repairing the structure of the mill due to its hardwood characteristics and its resistance to rot. This would provide the best chance for the structure to last. The machinery would be crafted from oak, applewood, beech or hornbeam – these woods were durable and easy to replace if the cogs broke. Waterwheels were originally crafted from wood before they could be cast. The millwright would construct the rim out of oak and the paddles of elm. This would be less susceptible to rot and prolong the life of a waterwheel. Wood was therefore the traditional choice of material for the millwright, and it still features heavily to this day. Not only is it important to the authenticity of the repairs, but wood is also easier to replace and more cost-effective than other materials. Read about other materials millwrights would use here: https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/millwrighting/#content2 |

The millwrights of the past and present

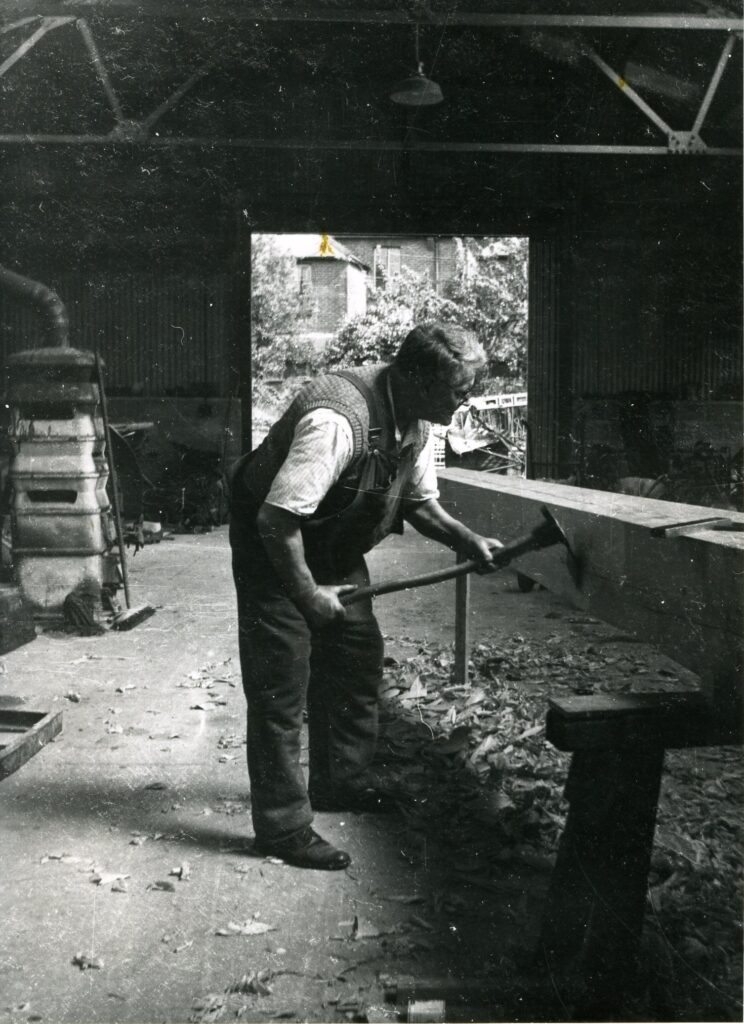

The third section of the exhibition contrasts the millwrights of the past with the millwrights of today. In the past, millwrights would have had to complete their work with traditional hand tools such as the saw, different types of planes and the adze, and they would do this in precarious conditions without safety equipment. However, technological advances and modern tools allow modern millwrights to be more efficient, and the introduction of safety equipment has made their job safer to complete. By highlighting the contrast between the past and present, it is evident that technological advancements have assisted the development of the craft.

Find out more about millwrights past and present here:

https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/millwrighting/#content3

Bob Barber adzing a midling for Black Mill, Barham, 1954

(Mills Archive Collection, HOLM-04-HB005)

Who are the millwrights?

(Portrait by Sir Henry Raeburn, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1810)

| The final section of the exhibition focuses on some of the highly regarded millwrights who mastered the craft. Two of these millwrights were active in Britain around the time of the industrial revolution – these were John Rennie and John Smeaton. Though Smeaton didn’t consider himself a millwright, it is evident he contributed extensively to the craft, making significant improvements to casting iron. The other two biographies in this section focus on contemporary traditional millwrights who dedicated their careers to restoring and preserving mills in Britain, Christopher Wallis and Vincent Pargeter. Wallis dedicated a significant amount of his career to restoring the Lacey Green Mill in a voluntary capacity, whilst Pargeter acted as the County Millwright for the Essex County Council from 1975-2000 and restored five mills. Read the biographies here: https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/millwrighting/#content4 |

Christopher Wallis (1935-2006), millwright. Photo by M Cookson

| The exhibition’s aim is ultimately to educate and bring awareness of the important skill of millwrighting and the role it plays in our heritage, with a focus on the material we have here at the Mills Archive. We hope that there will be a renewed interest in the skill which will result in an uptake of training and, in turn, its removal from the HCA’s Red List. |

We are grateful to the Swire Charitable Trust who have funded this project.