Dr James G. Moher

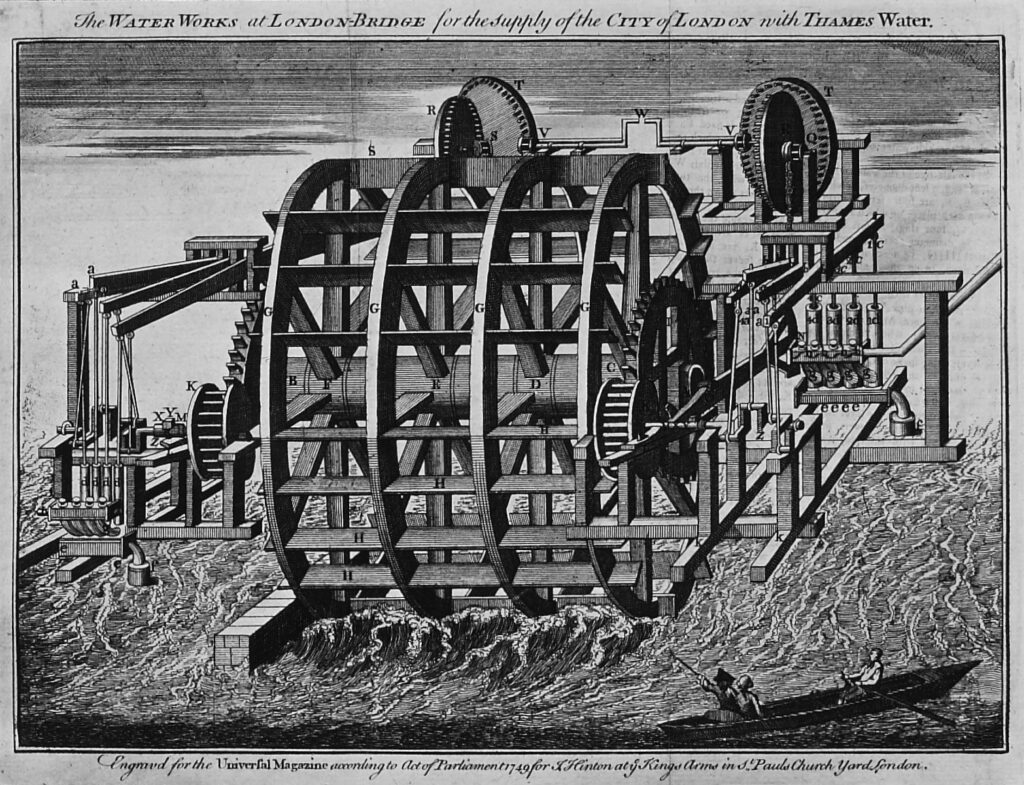

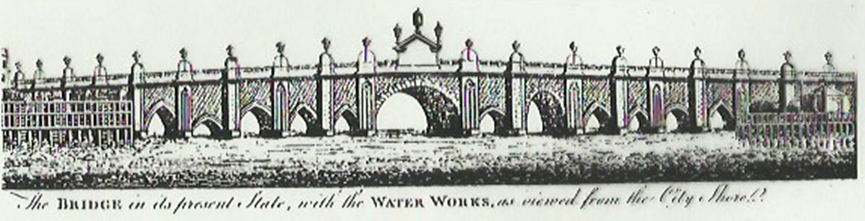

| Many are familiar with this historic but long-gone structure, which forded the mighty river Thames, but how many know that it had a major waterworks in its arches driven by huge millwork trains of wheels? Or that it drove corn mills at the southern end? A glimpse of what was once the London Bridge waterworks is just visible in the northern corner of the bridge, beside the church of St Magnus the Martyr. In fact, in its heyday five of the arches had elaborate wheeled pumping mechanisms to power the water supply to the City of London. The following sketch of an early one of those truly magisterial millwork wheels and pumping mechanisms gives an idea of the scale of the works. They were said to be superior in performance to that of the famous Royal Waterworks at Marley which supplied the Palace of Versailles before the French Revolution. | |

(Philosophical Transactions Vol.37, (1731). These amazing twenty foot or more diameter wheels were made and installed by George Sorocold, a master millwright of Derby in 1700. Henry Beighton (1636-1743), Fellow of the Royal Society, who had one of the wheels engraved in 1731 to illustrate his theories, was one of the earliest engineers and experimenters in large water-wheel construction)

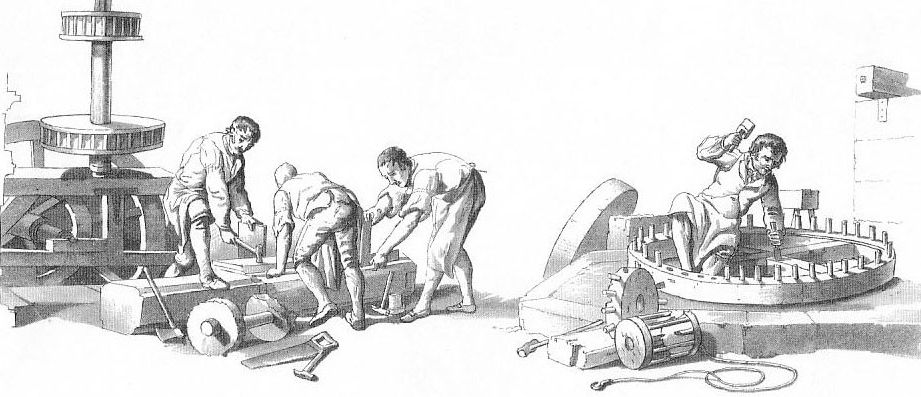

| This enormous pumping apparatus required continuous repair and maintenance, as it was subject to the constant pounding of the Thames’ tides and severe attacks of frost and ice in winter. Millwrights were the key workers and the company employed three permanent ones ‘to attend them from 6 to 6…and to take due care that all the wheels and engines be kept in good repair’. So highly were these men regarded that, ‘for their encouragement their wages are extra and always continued in the same pay in case of sickness’. These would be supplemented by contracting millwrights for major overhauls of the wheels. A beautifully handwritten report by the Waterworks’ Surveyor, Samuel Hearne in 1745, gives a detailed description of each wheel and pumping apparatus at that time (This folio-sized work is entitled, The State of the London Bridge Waterworks Anno 1745 by Samuel Hearne, company Secretary and Surveyor. Greater London Record Office, ref. Acc.2558/LB.1/1-9.). Of particular interest is that they were probably the earliest (c.1701) users of cast-iron millwork (gudgeons, ‘rounds of wallowers’, and cogs or spur wheels, spindles, cranks, wedges, and trundles). However, as the quality of cast-iron available then was poor and very liable to breakages, the craftsmen concerned must have been of the highest quality to work with it. The more usual material they had to work with was, of course, wood and a key task for the master millwright was the procurement of the best quality wood from all round the Home Counties. By 1745, there were five waterwheels and sixteen pumping engines in the first, second and fourth of the northern end arches of the bridge, working 52 water pumps by the power of the flowing and ebbing tide of the Thames. They were said to have pumped over 130,000 gallons of water an hour to a 120-foot tower beside St Magnus the Martyr’s church, which was then pumped by gravity through a system of wooden water-pipes to the burgeoning residential and industrial customers (‘distillers, sugar-bakers, brewers and public inns’) in the City area and to the Southwark area south of the bridge also. When John Foulds arrived at these waterworks in the early 1760s, the entire business was entering a critical phase. Essentially a bridge mill, it was the dimensions of the arches, due to the great width of the sterlings which supported each pillar, that provided ideal conditions to work water-powered machinery: a rapid and heavy fall of tidal water. However, the growing commercial demands of navigation interests on the Thames increasingly conflicted with the dam-like effect of the waterworks. This conflict created regular controversy on the City of London Corporation, which regulated the bridge, river and works. In 1761-2, they acceded to pressure for better navigation conditions by opening a larger waterway at the centre of the bridge. But this reduced the force of water available to power the waterwheels. So, an additional arch, third on the north side, was leased to the Waterworks Company and in 1766, the use of the fifth arch on the north side was also granted to them. | |

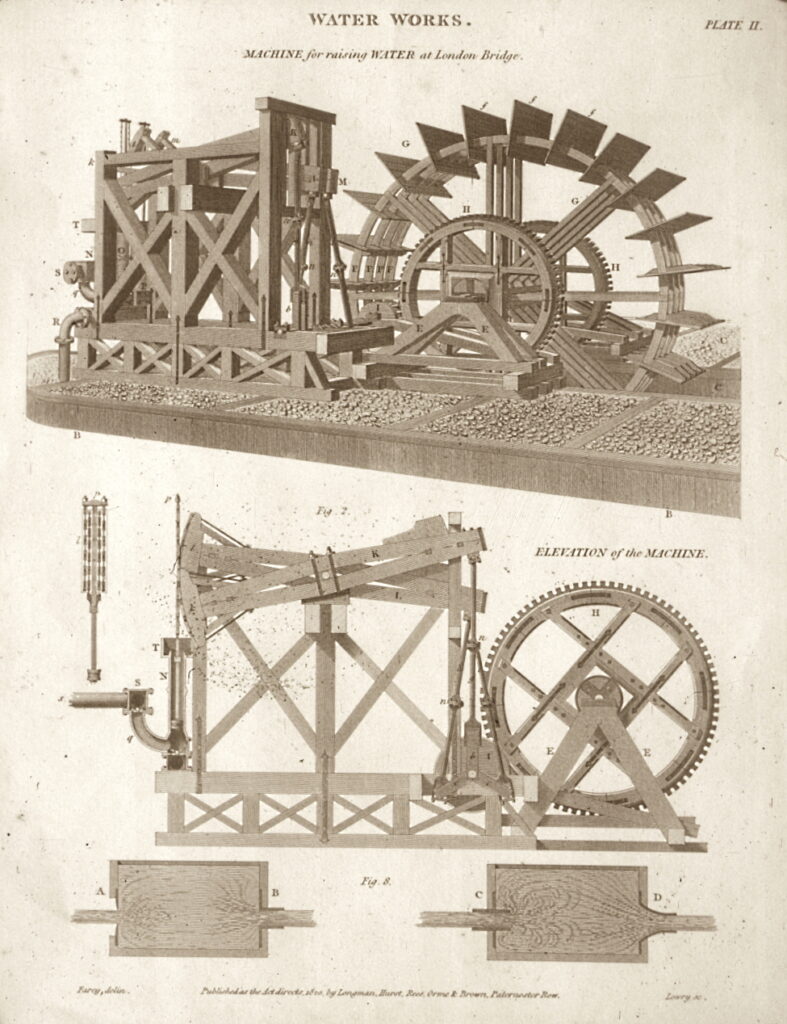

By the 1760s, the City of London Corporation had acceded to their request and allowed the waterworks company to put another large wheel in the enlarged central arch, as well as one on the Southwark side. This wheel was designed by John Smeaton and installed by one of his master millwrights, Joseph Nickalls of Blackfriars.

Yet this wheel and millwork disappointed both in its longevity and efficiency, and it was replaced in 1789, by one, said to be, ‘built in a much stronger and better manner than the old one was’.

This renewal was part of a wider programme to overhaul or replace all the wheels during the 1780s. This massive undertaking was supervised by John Foulds, their Chief Millwright, from Derbyshire, who had been with the company since 1763. He married Lydia Powell in 1765 in St Saviour’s Church, Southwark and so probably lived on the south side then. Unfortunately, the Company’s records date only from 1776, the earlier ones having been destroyed in a big fire in the tower and workshops, in 1779. Nevertheless, those that survive, especially the minutes of monthly Board meetings, paint a vivid and continuous picture from then until 1821, when the waterworks were removed. By 1776, Foulds was the Chief Millwright on a salary of £7 11s, with a house leased cheaply in Churchyard Alley on the north side.

Smeaton’s ‘Great Engine’ for the central arch. 1767-8

The fire at London Bridge Waterworks – October 1779 | |

In October 1779, the 120ft tower and workshops burnt down. This caused a serious disruption of the service, as the water was first pumped to the elevated position for delivery by gravity down to the mains throughout the City. Foulds led the firefighting operation which prevented the entire waterworks being destroyed and directed the rapid restoration of the supply by means of their standby atmospheric pumping engines. He went on to devise a metal Receiver and Distributor apparatus through which the wheels pumped directly to the mains, which obviated the need to rebuild the tower. This established Fould’s reputation as an ingenious craftsman and he turned his talents to many other mechanisms. In 1780, he received the Silver Medal of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce for another invention. This was an improved method ‘for taking off the power from the waterwheels to the pumps, saws or other mechanical operators.’ | |

The Society headquarters were close to London Bridge and the Secretary, Samuel Moore, seems to have regarded the waterworks as a testing ground for numerous other technical innovations. Periodic applications from the Society to the Waterworks’ Management Committee appear in the Company minutes, on which Foulds’ expert opinion was always sought. At this time, November 1779, another eminent millwright/engineer, Thomas Yeoman, FRS, submitted his ‘model by way of balance for supplying the water without the tower’ to the Committee, but this was returned unopened on account of Foulds invention satisfying their need. | |

The Waterwheel and Millwork Rebuilding Programme 1782-90 | |

Foulds was now responsible for the maintenance and periodic refurbishment of the entire technical side of the establishment at the bridge, i.e., the waterwheels, millwork, pumps, fire-engines and mains apparatus. The demands of such varied duties stimulated his development from that of superior craftsman/artisan to that of professional engineer. In 1794, the Committee of Management reported that since 1782, they had had to install a Steam Engine upon the improved principle of Boulton & Watt. Foulds worked closely with the great inventor, doing the designs for a section of the existing atmospheric engine for which the Company gave him a Gratuity of £21. His draughtsman talent earned him regular payments of this kind. Both Boulton and Watt attended a meeting of the Management Committee in March 1784, and their steam engine was erected in 1786 as the prime back-up to the great wheels. Foulds had responsibility for rebuilding five wheels ‘to counteract the decrease of power at the Works arising from the Great Arch …as the ebb tide now runs out much sooner than it formerly did.’ Preparations for taking down and repairing the wheel in the second northern arch began in September 1786, with Foulds visiting many timber sites to procure suitable materials. This was a major responsibility of the Chief Millwright, to ensure the right quality, dimensions, and supply of the enormous quantities of oak, elm, hornbeam, and other hard, water-resistant wood, necessary for such large wheels. Hertfordshire and Sussex were Foulds’ main sources of supply. The new wheel was in place by November 1787. In 1788, he tackled the first arch wheel, and a new wheel was in place by August. These wheels were designed and built to the highest standards of the time, with Foulds’ ingenuity and skill. The minutes of 12 September 1788 record the Management Committee’s satisfaction with these first two new wheels, which ‘raise considerably more water than the old ones did.’ In 1789, Smeaton’s Great Engine in the fifth arch was replaced by one ‘built in a much stronger and better manner’. That same year, operations began for reconstructing the Borough-side wheel. They had a ‘horsepath engine’ at the south end of the bridge as a standby power. These plans had to be postponed until Spring 1791, while the sterlings around the arches were repaired. The new wheel was eventually installed there in April 1792. Work commenced immediately on the northern third arch wheel which was completed by Christmas 1793 and its superior performance was again commented on. In 1795, a sixth wheel in the fourth northern arch completed the programme for some time. Foulds had been rewarded in April 1792 for masterminding and carrying through this impressive reconstruction programme with a promotion to the Senior Staff as Chief Millwright (Minutes of the Management Committee, The London Bridge Waterworks Company, formerly held in the Archives of the Thames Water Authority, Metropolitan Water Division, New River Head, Rosebery Avenue, London ECI, where the author first consulted them. They are now in The Greater London Record Office (GLRO), Ref. Acc.2558/LB/1/1-9). The minutes record, ‘In future Mr Foulds will not receive his wages weekly, but that he be paid a salary of £100 per annum by four quarterly payments’. His previous basic wage was just £25 per annum, supplemented by regular gratuities. This salary was increased to £120 per annum in September 1796 and he continued receiving regular gratuities of £50 per annum until his death in 1815. From the 1790s, he also acquired a leasehold interest in one of the large company houses in Churchyard Alley, just beside the bridge, at a much-subsidised rent. Foulds’ eldest son, John Powell, joined him as an apprentice millwright in 1788 and showed much promise, as witnessed by his drawing of the new Borough wheel in 1793. Sadly, John Powell died a few years later aged only twenty-two. Foulds’ younger son, William (b.1782) was also apprenticed at the waterworks and in time became the leading millwright with the company, with a house at a low rent. Tragically, he also predeceased his father in 1814, aged thirty-two. | |

Foulds and the Society of Journeymen Millwrights | |

| The extensive millwork programme, carried out between 1782 and 1796, attracted many contracting millwrights to London Bridge, in addition to the permanent men. The Minutes record the continuous payment of their wages by Foulds, and it is interesting to consider his relationship with them as a Master millwright. The usual pattern was for a master to act as an independent contractor of labour and materials moving around from customer to customer. However, Foulds remained an employee (staff laterally) of the waterworks company throughout his life, yet he was regarded as one of the leading London master millwrights, hiring and paying the journeymen and apprentices himself. John Rennie, the Scottish master, on arrival at the Albion Mills along the river at Blackfriars bridge in 1784: ‘made it his duty to consult the most eminent Masters in London such as Mr. Cooper, a Gentleman well known, and Mr Foulds (Engineer of the famous London Bridge Waterworks), as to the usages then adopted in the trade.’ (‘Mr. Cooper’ refers to John Cooper of Holborn (1742-92) or his brother James of Poplar (d. 1801), a leading millwright family business, who did many of the London brewers and distillers’ conversions from horse- powered to steam-driven wheels and millwork. For the writer’s account of John Rennie’s operations at the Albion Mills, Blackfriars, see Mills Archive Newsletter December 2021). Foulds was an important figure in the Master Millwrights’ Association, which was formed in 1778, as a response to the strong combination of London journeymen whose club was formed in 1775. There was a London-wide strike in 1786, though the waterworks doesn’t appear to have been much affected. However, the introducer of advanced steam engines to London, James Watt and his Soho works partner, Matthew Bolton, were. Their advice was to replace millwrights with carpenters where they could, ‘for everything they can do’- an important qualification as the highly skilled millwrights were not replaceable easily. But in 1795 both the permanent and casual millwrights at the bridge were ‘in the thick of it’ – a strike which lasted from July to November. The management of the waterworks, led by Foulds and the company secretary, Richard Till, strongly resisted the men’s’ demands. The dispute became very bitter when Foulds substituted non-Society journeymen millwrights and carpenters for those on strike. This drew a strong reaction from the strikers, who tried to prevent the non-Society men taking their places. The City constables were called in to prevent this (one of the City aldermen sat on the Company’s Board) and it appears that in the end the journeymen had to return on the Management Committee terms. Foulds was rewarded for his efforts with a commendation and ten guineas ‘for the expenses incurred in procuring Millwrights and Carpenters.’ These master-journeymen millwright battles came to a head in 1799, when the masters obtained a Bill in Parliament to outlaw the journeymen’s club and impose wage-fixing on the trade. Foulds got the Waterworks Company to contribute the sizeable sum of £30 towards the expenses of the masters’ parliamentary campaign. However, it didn’t become law, being overtaken by William Pitt’s wider Combination Act outlawing all such combinations in 1800 (Moher, J, The Combination Laws and the Struggle for Supremacy in the Early Engineering Trades: The London Society of Journeymen Millwrights (Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 2018), pp.1-30). | |

Foulds was appointed Assistant Engineer in the Surveyor’s Office of the Corporation of London in 1791. He had responsibility for superintending and directing the repair of London Bridge, its huge abutments or ‘sterlings’ and foundations. The Waterworks Company agreed to this dual responsibility ‘consistent with his duties as Engineer and Chief Millwright of these works.’ He was paid £100 per annum by the City Corporation. This post required him to mix increasingly in Corporation and professional engineering circles. In 1793, he was admitted to the very exclusive Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers, in the artisan category. This society included many of the most eminent consulting engineers of the day such as John Rennie, William Jessop, Robert Mylne, Bryan Donkin and many others.

A contemporary map of the London Bridge Waterworks and the streets around, where the Society of Journeymen Millwrights had their ‘Houses of Call’ (pubs). This is from Richard Horwood’s 1792-1799 survey

Fould’s role in the creation of the West India Docks | |

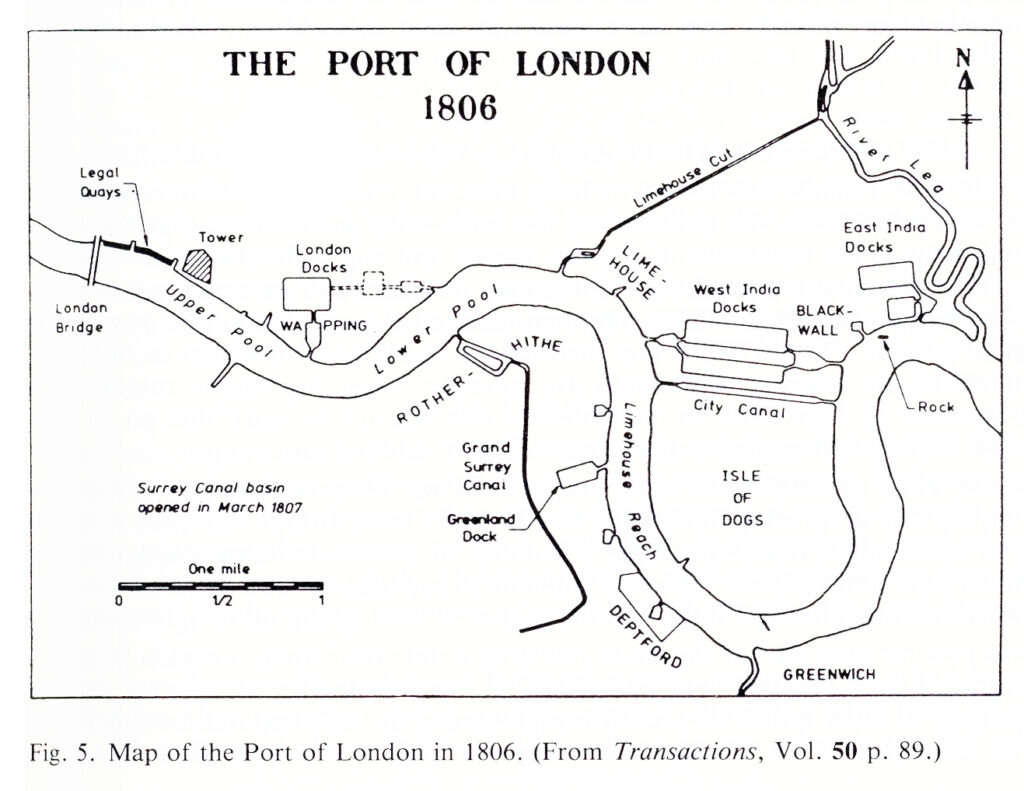

| When plans to transform the Port of London from a congested and pilferage-ridden open system came to fruition towards the late 18th /early 19th century, engineers were engaged to devise and design an enclosed system of wet docks. Most of these plans originated from the West and East India merchants and planters’ pressure on the Corporation of London and the Government, to improve the mooring and warehousing facilities of the port. On completion, they would make London one of the greatest ports of the world and famous engineers like John Rennie and William Jessop figured greatly in this achievement, as is well known. Less is known about the contribution of those like John Torr Foulds who acted for the Corporation. | |

Plans originally centred on the existing Legal Quays which were just below London Bridge and Waterworks and were then the main customs area. Foulds’ part of the first report of April 1794 ‘on proposals for improving the Legal Quays’, was a joint work with William Jessop and John Rennie, the Consulting Engineers for the merchants (A.W.Skempton Engineering in the Port of London 1789-1808, Transactions of the Newcomen Society (T.N.S.) vol.50 (1979), pp.87-108 at 88). It addressed the problems of pilferage, congestion and inefficient loading/unloading of tobacco, sugar, and other commodities as well as secure warehousing, and the possible use of steam engines for working cranes. No action followed until 1797, when agreement was reached between the Corporation and the merchants for a completely new system of wet docks, further along the river on the Isle of Dogs. With Foulds assisting Jessop and the Corporation’s Clerk of Works, George Dance, they devised two parallel and linked docks with a ship canal also linking the Limehouse and Blackwall entrance to the Isle of Dogs. (see map above) This was to become the famous West India Docks. Credit for these magnificent civil engineering works has gone largely to the consulting engineer, William Jessop, yet it is clear from the daily journal kept by George Dance that Foulds was regularly in attendance with Jessop and Dance. So, he played a not inconsiderable role in the planning stages of the Docks and in the execution of the early phase of the City Ship Canal (Dance’s Journal (Guildhall Library), 1792-1801, vol.2, p.91). Other reports on the soundings of the river in 1796 are contained in the Printed Report. He gave evidence to a Select Committee of the Commons where he said that his views were based on ‘31 years as an Engineer to London Bridge Waterworks around that part of the river.’(Ibid., vol 51, p.193).

| Foulds’ mechanical engineering inventive abilities are again shown with Dance, ‘attending Mr Foulds and making copies of his invention for admitting ships into the half-tide docks’. He claimed he was ‘being put in charge of the mechanical engineering aspects of the City Ship Canal, Mortar Mills, pumping machinery for de-watering the excavations’ and so on. Agreement in principle on the site for the West India Docks was reached by August 1797 between the Government, Corporation and Merchants with ‘Mr Foulds collecting his ideas and making drawings for wet dock, canal half-tide dock etc…with a site for corn mills, granaries…’ It is not certain whether the corn mills were built. His draughtsman skills were again valued highly. The Bill approving the establishment of the West India Docks passed in July 1799, with Foulds engaged ‘taking levels on the Isle of Dogs and Wapping’, as well as ‘combatting alternative proposals for rebuilding London Bridge’. He was not able to complete this project, perhaps because of more pressing demands on his time at the Waterworks. Foulds also acted as Engineer to the Shadwell Waterworks just along the river. An unidentified logbook with entries from February 1797 documents his close involvement in the replacement of a fire engine and engine house which had been destroyed by fire in December of that year. He first took draughts and presented plans for a replacement Boulton & Watt improved Engine in January 1798. He then directed the erection of the new engine and house, attending regularly from May 1798 to give instructions to all the contractors, including the millwrights involved. The period 1775 to 1805 must then be seen as one of extraordinary energy and remarkable achievements in the City area between London and Tower bridges. In 1805, then aged 63, Foulds remarried to Jane James, but increasingly several periods of long absence for gout, rheumatism and other ailments afflicted him. Working in all weathers for such a long time began to take its toll. He was still able to superintend and direct the overall maintenance of the Waterworks through his younger son William, who was then the leading millwright there. However, time was running out for the Thames-powered waterworks under the old bridge also. The merchant interest in improved port facilities was added to the existing navigation interest. Hostility to the continued existence of such a narrow-arched bridge spread in the Corporation and Parliament. In 1809 John was active enough to give his valued opinion on the prospective expenditure the Company might require on the waterwheels, gallery and steam engine for the foreseeable future. He estimated the life of the various wheels and suggested immediate improvements. In 1814, the shaft of the main wheel under the fifth arch gave way, causing a crisis for the management as it was crucial to replace it as soon as possible. The Chief Millwright, then aged 72, was sought urgently to advise, through his son, who conveyed his report to the Management meeting. He persuaded the Company that matters were not so grave and that the wheel could be repaired and improved. William carried out the repairs, by strengthening the wheel with four iron plates. However, events were to render a replacement necessary. Firstly William, the Leading Millwright, died in September 1814, aged only 32, leaving the Waterworks without a key millwright. 1814-15 was the most severe winter for about eighteen years, the heavy frost causing further deterioration of the 5th arch wheel. Accordingly, in 1816 it was decided to engage a firm of outside millwrights, Hunter and English of Bow, to carry out the repair job, which they did in 1817, with a fully cast-iron waterwheel. John Torr Foulds died on 10th February 1815 aged 73 years, fifty-two of which he passed in the service of London Bridge Waterworks. Just a few weeks before he died, he was consulted by the managers about the frost damage to the fifth arch wheel and typically he recommended ‘an application which would prolong its life for two or three years more’. Clearly, his feeling was that time was running out for the water-powered engines under the arches of London Bridge. However, instead, the Company installed an advanced iron waterwheel in 1817. Foulds wasn’t wrong as in 1822 the waterworks were dismantled by Act of Parliament, with compensation to the proprietors and the machinery transferred to the New River Company on the Lea. What happened to the three permanent millwrights is not clear. | |

Conclusion | |

| We have no visual impression of John Torr Foulds, only his signature to the 1794 Legal Quays Report, together with his drawings. Clearly, he was a strong country man of considerable stature (millwrights had to be then, as there was not a lot of equipment to save the back-breaking part of the job, unlike today). However, unlike most artisans of his time, Foulds’ bent for study and experiment in all matters mechanical and hydraulic marked him off from the ordinary master or journeyman millwright. London Bridge Waterworks, with its large workshop and best available tools, facilitated his bent. Millwrighting was then a very traditional, if superior craft, based on inherited knowledge from father to son and learned through time-served apprenticeship (seven years was the usual term, enforced by the Journeymen’s Society). The fact that the Waterworks was near the offices of the Society for the recently founded Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce, who used it for experimentation, gave Foulds access to some technical literature and perhaps discussions with scientists and engineers which he fully availed of (his Silver Medal in 1780 showed this). His membership of the Smeatonian Society (artisan section) was another opportunity to ‘brush shoulders’ with the eminent engineers (many former millwrights) of the day. He was one of the best-known and most respected master millwrights in the London trade and an active member of the Masters Millwright Association. His battles with the London Journeymen Millwrights Society and the casual journeymen he had to hire from the local ‘House of Call’ (the Swan, Old Fish Hill, near the bridge), during their major restoration programme from 1780 to the 1790s, shows him as a tough all-round character (See The Combination Laws and the Struggle for Supremacy in the Early Engineering Trades: The London Society of Journeymen Millwrights for an account of these industrial relations side of the London trade). Foulds was a family man, ensuring that his sons followed in the trade, but tragically both died having shown great promise, but before they could build on his many achievements. This misfortune must have grieved him deeply. We have a vivid painting of the site of the area of Foulds’ activity, with the ruins of the old London Bridge. | |

| This is an edited version of a paper and talk I gave to the Newcomen Society for the study of the history of Engineering and Technology in 1986. Vol 58 of the Transactions TNS 1986-7. Reproduced by permission of the Newcomen Society. | |