| Following an excellent, well-illustrated article by Willem van Bergen in International Molinology, 2020, 101: 2-9, the Mills Archive Trust has published the above book as our 13th Research Publication. Brief extracts follow and a limited number of single copies will be available on our bookshop in return for a small postage charge using this discount coupon nisb2020. We will also be making a digital download version available online soon. We will let you know when that is available on our website. |

| ‘Prior to 1600, sugar was a costly luxury in Britain, available only to the rich. All that changed through the 17th century with a rising domestic demand for sugar as a sweetener in tea, coffee, jam and confections. Through the 18th century sugar consumption in Britain increased by a factor of five to become an everyday necessity. This consumer demand drove an agricultural, commercial and industrial revolution to cultivate, process, market and refine the sugar. The technological heart of the process was the sugar mill.’ |

| ‘Traditionally a paper covering sugar mills would be devoted almost entirely to technology and invention. However, this omits the human factor: that sugar mills were operated by enslaved Africans. A great deal has been published regarding African slavery and the technology of the sugar mill. However, the topics have rarely been brought together. This new work balances both topics using a case study of one planter family operating on two Caribbean sugar islands St Kitts and Nevis and concludes that, as in British industry generally, it is inappropriate to separate the work force from the technology. Following a brief discussion of research into slavery, the book looks at the evolution of sugar cultivation and milling. The application of sugar mill technology to the Caribbean addresses the importance of topography, the lack of wind and rain, the uncertainty of hurricanes, and the ease of repair or availability of spares in a frontier environment. Mill work was particularly stressful due to the nature of sugar cane, its long gestation and rapid spoiling combined with breakdowns, unguarded machinery, long shifts, and ambitious overseers. Although in Europe there was a general progression of technology following the move of sugar cultivation from the eastern Mediterranean, out into and across the Atlantic, the global progress of mill technology was not necessarily logical. For example, some problems experienced by Europeans in the 16th century had been resolved much earlier by the Chinese. Within European experience, there was a gradual evolution, irrespective of nationality. In the 17th century, the early British and French sugar plantations on Caribbean islands relied heavily on earlier Dutch and Portuguese experience in Brazil. ‘ |

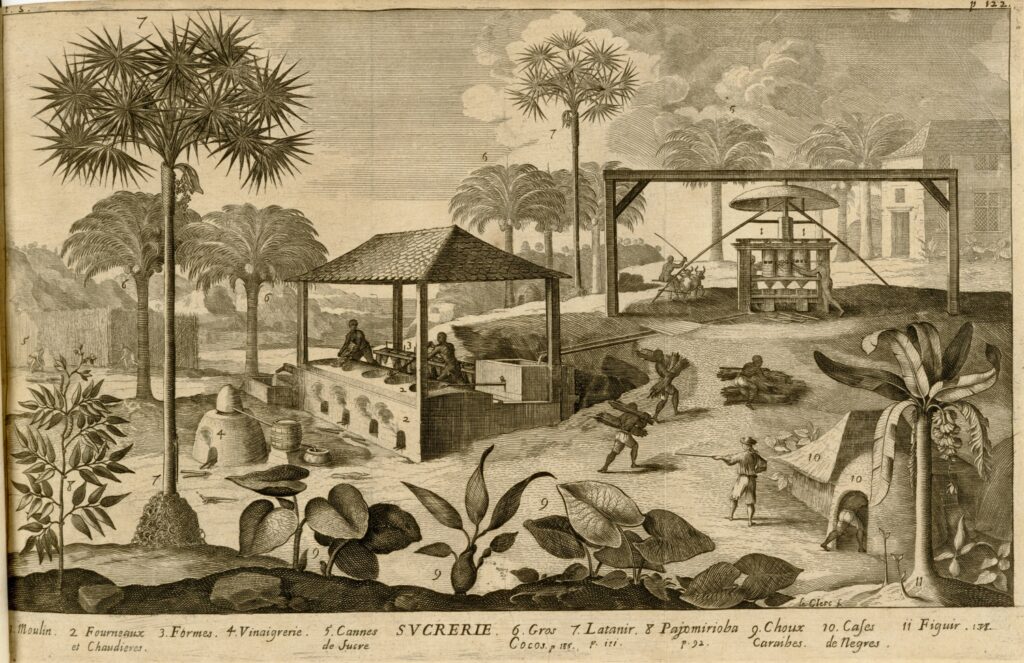

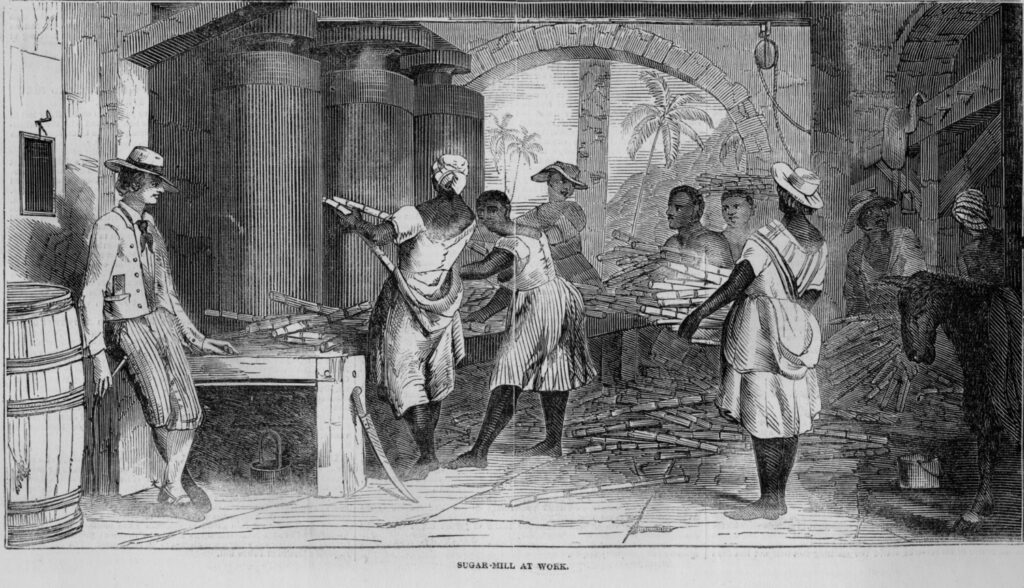

| ‘Research on any aspect of slavery quickly becomes harrowing. Men, women and children were enslaved, then transported in deplorable conditions in which many died. Those who survived and their descendants, were over-worked and often mentally, physically and sexually abused on plantations. It becomes necessary to lace every sentence with condemnation of the evils of slavery. For more than a century from the 1660s, virtually nobody in Britain questioned the morality of slavery. From the 1770s onwards, growing opposition led to the abolition of slave trading by British ships in 1807. However, it was not until 1834 that slave ownership was banned in the British Empire, including the British sugar islands. In some countries it took longer. The process of understanding is still incomplete, and by seeking to take a balanced approach to introducing sugar mills and slavery, this paper is one small contribution. Historians, such as David Olusoga, have stressed the neglect of the significance of slavery and slave-grown staples in the history of British industrialisation. Indeed, early industrialisation was made possible by the exponential increase in enslaved labour in the colonies to produce the necessary raw materials. Recent studies have shown that thousands of British citizens owned enslaved people on sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The cane mill and sugar works needed a large labour force to operate. The purpose of traditional illustrations of sugar mills was often to illuminate the main elements of the process, however they were often stylised. For example, this figure shows an ox-drawn mill with vertical rollers and the furnace and boilers in which the sugar juice (coming down the gutter from the mill) is boiled. Largely devoid of labour, such images fail to convey the bustle and general stress of the milling process.’ |

| ‘With all types of roller mill, one or more labourers, often women https://new.millsarchive.org/exhibition/sugar-slavery/, fed the cane stalks between the first and second rollers. Labourers at the other end bent the crushed stalks as they came through and fed them back between the second and third rollers. The space between the rollers was c.5 to 10mm, with the gap between the second and third roller being narrower, to extract more juice. The narrower the gap, the more juice that could be extracted, and the more power was required, but if the gap was too narrow, it would not receive the cane. Thus, skill was required to determine the optimum setup.’ |

The Illustrated London News (June 9, 1849), vol. 14, p. 388 (Slavery Images)

| ‘The enslaved workforce had a direct input to the wealth and success of the planter and the home country, but plantation workers have traditionally been seen as chattels, working on distant colonies, with little relevance to British industrial history in general, or mill history in particular. Modern research requires a wider view, which takes into consideration the human factor. The human cost of sugar mills was high. Most general accounts of cane mills stress the physical hazards. The long shifts were necessary to keep the mill operating night and day. “Work on a sugar plantation was arduous and labour-intensive throughout the year, but was particularly onerous at harvest time when the sugar works operated incessantly, with the workers organized in shifts to keep the operation going” (Dunn, Sugar and slaves: the rise of the planter class in the English West Indies, 1973). An early account expressed the primary hazard: “if a mill-feeder be catch’t by the finger, his whole body is drawn in, and he is squeez’d to pieces”. Wind and water mills could not be stopped quickly enough to prevent a worker being drawn through the mill roll. Almost every account of sugar mills mentions maiming and death, through workers being drawn through the mill. The fitting of guides to assist feeding the cane into the mill helped reduce accidents. However, even a century after the abolition of slavery, a study of a surviving cane mill on Nevis recalled workers, within living memory, who had lost limbs or had been drawn through the mill and crushed to death. In many instances, an axe was kept beside the cane mill, to chop off a hand or arm, to prevent the whole body being drawn in. The intensity of working and tiredness of the workers increased the danger. The book concludes by emphasising the need for research on sugar mills and slavery requires a modern, multi-disciplinary approach, avoiding the often-narrow focus of traditional research. Although the author concentrated on two British plantations it has direct relevance to the plantations of other colonial powers. The supply and use of enslaved Africans was an international business. There was also often an overlap with technology.’ Dr Stuart M Nisbet has published extensively on aspects of slavery, mills and the history of Scotland, with a particular emphasis on Glasgow including a detailed study of two of the city’s earliest pioneers on sugar plantations in the Leeward Islands. |

Sugar and Slavery: Reproductive Mills

| This exhibition sheds light on the links between technological developments in sugar milling and enslaved women’s reproductive systems, especially in the early nineteenth-century before the abolition of slavery. The exhibition uses images from the Caribbean islands from the period of slavery and beyond in order to map the transition of both women and machinery from ‘disposable’ to ‘vital’ in the eyes of enslavers. ‘Sugar & Slavery: Reproductive Mills’ is a digital exhibition written by Jude Reeves, a second-year undergraduate in the Departments of History and English, with the assistance of Emily West (Department of History) and Elizabeth Bartram (Director of the Mills Archive). The student placement has been funded by the University of Reading’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities (UROP) programme, with additional funds from the Garfield Weston Foundation to create the digital exhibition. |