| Since the creation of mills, whether powered by water or wind, the need for their construction, repair and maintenance has also existed. Evidence of millwrighting has been noted across the world and across centuries from the Ancient Greeks and Romans to the Byzantine Empire and Medieval Europe and, finally, to Modern Britain. Though the term was not coined until the 14th century, the art of millwrighting has played a significantly important role in the life-cycle of milling, which over time has helped feed and power numerous civilisations. The skill of millwrighting is one learnt hands on, with the skill, at its peak requiring a seven year long apprenticeship to master. Though mainly identified with woodwork, millwrighting, as Sir William Fairbairn rightly pointed out, required more than just that. In his words, the millwright of later centuries was an ‘itinerant engineer and mechanic of high reputation’ who could ‘handle the axe, the hammer, and the plane with equal skill and precision.’ | |

| John Langdon highlights that in the early 14th century there were somewhere between 10-15,000 water- and windmills in England alone, though not all of the structures were impressively constructed. Around this period the term millwright was coined and became synonymous with the term carpenter, as evident in nearly all surviving records. Though a small number of tower mills were built in the Middle Ages, the craft of millwrighting was increasingly dominated by the use of timber. The terms millwright and carpenter became interchangeable because the most popular type of mill in this period, the post mill, was crafted from timber as it was cost-effective to create and repair. The medieval post mill was, however, a fairly simple structure to assemble by today’s standards. Although timber may seem the most appropriate material to use in constructing and repairing a mill due to its wide availability, Langdon reveals that the use of wood may have been a deliberate ploy by carpenters and millwrights. By controlling the materials and skill that it took to repair the main components of the mills, the carpenter was able to dominate the industry, adopting various strategies to protect this position, such as using rubble masonry to construct tower mills, which could be completed by someone less skilled than a stone mason. However, in time, the creation tower mills required a specialised ability to craft the ‘batter’, the slope of the wall on a tower mill. This ‘batter’ would help protect the mill against rain and wind and extend the longevity of the mill. In all, the millwright/carpenter of the Middle Ages and their gate-keeping of the milling industry signalled the beginning of the growth of millwrighting as a traditional craft skill. | |

(Photo J S P Buckland, Mills Archive Collection, JSPB-ODR-288)

| Between the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution, the skill of millwrighting established itself as an invaluable craft. Over time, as mills evolved to become more technical, so too did the skills that constituted the craft of millwrighting. Early post mills were simple structures that extended from the ground on a post upon which the mill body balanced. They did not contain the specialized features that later mills featured, such as sack hoists or gearing mechanisms. Therefore, the millwright from around 18th century onwards had to maintain the traditional mill’s productivity by dressing the mill stones; as well as carrying out more specialized repairs to these newer features. Despite the technological advances to the milling industry of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, millwrights were still in significantly high demand. Martin Watts highlights this using the 1851 Census, which records around 10,000 millwrights ranging from traditional craftsmen who serviced water- and windmills to those attached to large engineering firms. It can be concluded from the 1851 census that the growth of the traditional craft of millwrighting peaked during the mid-19th century. | |

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, newer technology such as roller mills and steam powered mills became increasingly popular thus reducing the need for the traditional millwright, who usually worked with wood. However, this caused the traditional mill, powered by water and wind and using a pair of stones to grind flour, to decline alongside the traditional ways of millwrighting. Some mills adapted to roller technology, installing a small roller mill alongside their traditional means of milling to maintain their output year round. Nevertheless, only a select few water- and windmills may have been able to afford this luxury. Maintenance and repair of the new technology required a different type of engineering skill, skills that only a few millwrights possessed. In 1878 ‘nabim’, the National Association of British and Irish Millers, recorded a total of 8,814 flour mills within the United Kingdom, with only 5% of these classified as complete roller process mills. Later, in 1907, the first Census of Production received only 1,254 replies from milling institutions. Though the low figure could derive from the fact that it was the first census, it still suggests a steep decline in the number of working mills. In addition, by 1907 around 75% of the flour consumed in Britain was produced by the process of roller milling. This represents a move towards a more modern, industrial kind of milling rather than a continuation of traditional methods, resulting the further decline of the millwright. The 1911 census identified just 2,400 millwrights, a decrease of c.7,500 in the 60 years between 1851 and 1911. The decline of traditional millwrights from the mid-19th century could be attributed to the advances in milling technology, stimulated by the need to feed a rapidly growing urban population.

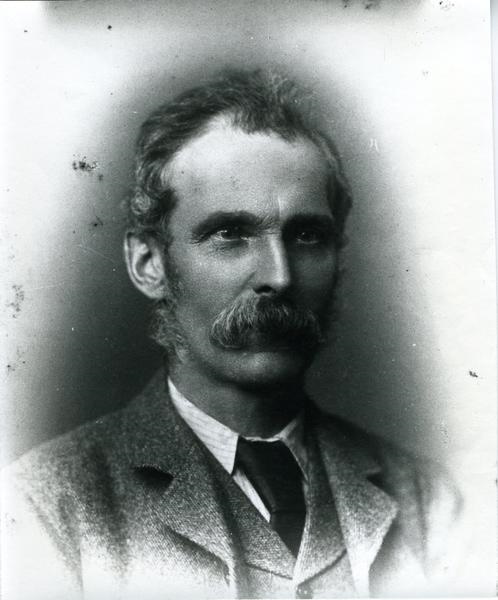

Thomas Richard Holman, Millwright c1850-1870

https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/thomas-richard-holman

(Photo F W Gregory, Mills Archive Collection, FWGC-1111503)

(Photo Michael French , Mills Archive Collection, FREN-26147)

Though millwrighting saw a small revival in the mid-to-late 20th century following a revival of traditional mills and their milling techniques, it never quite returned to its pre-industrial heyday. Having been put on the Heritage Craft Association (HCA) RED list for traditional crafts in 2019, the state of millwrighting today is bleak. In 2019, the HCA estimated that between 6 and 10 professional millwrights classed the profession as their main source of income, though in 2021 there are now 14. There are also around 20+ volunteers who can assist with basic repairs. This is considerably below the minimum number of craftspeople required to sustain the skill, with the association concluding that around 20 should suffice. The decline of the skill of millwrighting can be linked to various factors, the most important of which is funding. In addition, there is a lack of a recognised millwrighting qualification and training opportunities. Becoming a millwright requires hands-on training in the form of a seven year apprenticeship, but the slowly diminishing number of professionals is making this hard to achieve. Hands-on training is essential for the aspiring millwright to develop knowledge of the regional differences inherent in mills and the skill of millwrighting. Though the profession has a number of very competent volunteers who can do small jobs, without a solid number of professionals the craft will slowly but surely become extinct. Due to the considerable amount of transferable engineering skills that a modern millwright may need, it is worth considering an appeal to current engineers and/or skilled craftspeople who can learn the craft of millwrighting before it is too late.

Headstone, Denver Churchyard

(Photo Hallam Ashley , Mills Archive Collection, ASHL-23-005)

Sources John Langdon, The ‘Engineers’ of Mills in the Later Middle Ages, SPAB Mills Section, 2007 Martin Watts, ‘Milling and Millwrighting’, in E.J.T Collins (ed), Crafts in the English Countryside: Towards a future, Heritage Crafts Association, 2004 Heritage Crafts Association, ‘Millwrighting’, Red List of Endangered Crafts, 2019 https://heritagecrafts.org.uk/millwrighting/ | |