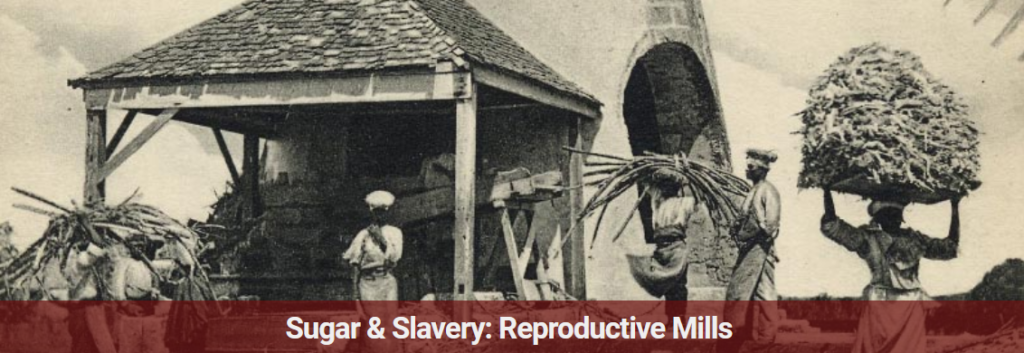

| Sugar & Slavery: Reproductive Mills is a new Mills Archive digital exhibition, launched in October 2021. It is the first of a series of online exhibitions. This exhibition sheds light on the links between technological developments in sugar milling and enslaved women’s reproductive systems, especially in the early nineteenth-century before the abolition of slavery. The exhibition uses images from the Caribbean islands from the period of slavery and beyond in order to map the transition of both women and machinery from ‘disposable’ to ‘vital’ in the eyes of enslavers. It is written by Jude Reeves, a second year undergraduate in the Departments of History and English, with the assistance of Emily West (Department of History) and Liz Bartram (Director of the Mills Archive). The student placement has been funded by the University of Reading’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities (UROP) programme, with additional funds from the Garfield Weston Foundation to create the digital exhibition. | |

The digital exhibition is now on our website, where you can explore it by visiting millsarchive.org/exhibition/sugar-slavery

| You will find four sections, which include milling innovation, enslaved women’s reproduction, and the situation of some of these mill sites today. Here is a sample of the exhibition, please visit the exhibition on our website to explore in full. 1807 saw the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, making illegal the importation of enslaved Africans to British colonies in the Caribbean. This meant enslavers were now unable to purchase new people from Africa, only those already in the colonies could be traded. When it was voted upon in Parliament, the Act passed with forty-one to twenty votes in the House of Lords and one hundred and fourteen to fifteen in the House of Commons. After decades of campaigning, it was finally illegal to export human cargo across the Atlantic, although trafficking between the Caribbean islands continued until 1811. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/abolition.htm | |

Figure 1 – Displaying the intensity of the process of producing sugar in British Antigua. Central to the image is the windmill which encloses a vertical roller through which sugar cam is being passed to extract the juice to make sugar as we recognise it. This image comes from ‘Ten Views in the island of Antigua’, Published 1823 by William Clark. These images are very important for telling us about the process of sugar mills, but we must be aware of the idealised version the images project.

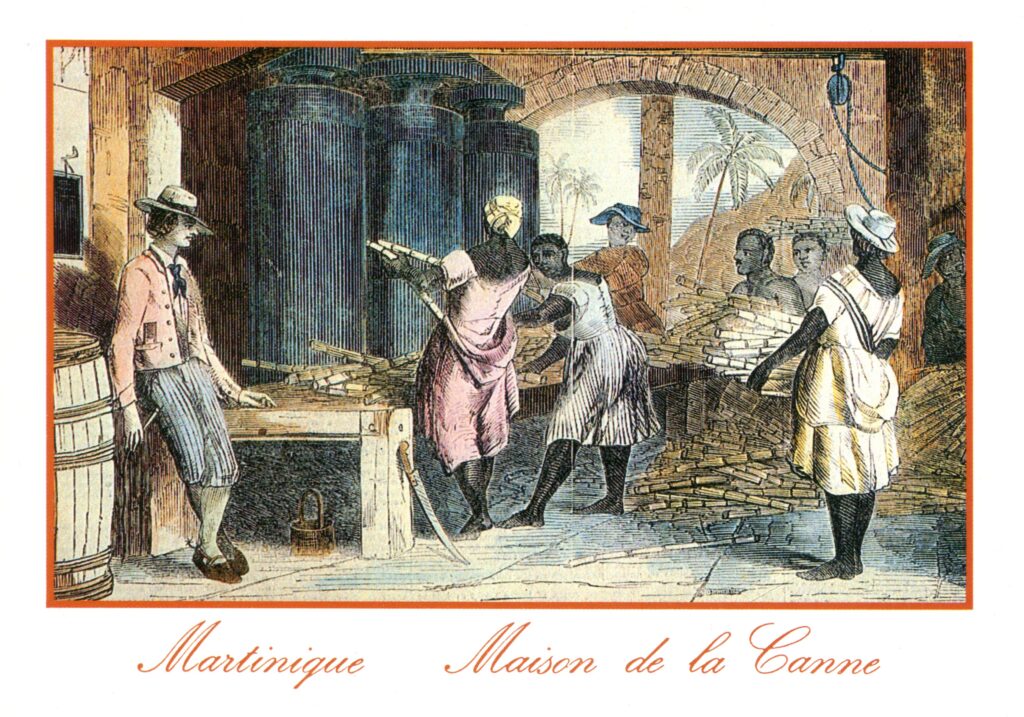

| After the 1807 Act, enslavers on British Caribbean islands faced the reality that their enslaved workers were no longer so easily replaceable. Instead, maintaining a population of enslaved people required more consideration by enslavers towards human reproduction on their plantations as a means of ensuring profitability on sugar plantations. Planters desired maximum efficiency from their sugar machinery and to generate the next generation of slaves to preserve the future of their plantations. Moreover, the process of industrialisation in Great Britain and the adoption of new technological innovations on Caribbean islands meant that this prioritisation of enhancing economic efficiencies on plantations was possible in a way that had never been seen before. Overall, then, the early nineteenth century saw some changes in slaveholders’ attitudes towards women’s fertility as well as heightened financial investment in sugar-producing machinery upon plantations. In the period prior to emancipation, slaveholders commonly favoured enslaved labour over machinery as the force driving efficiency on sugar plantations in the Caribbean. However, following the abolition of the international trade in enslaved people in 1807, as the region moved towards emancipation, planters began to invest more heavily in their machinery on sugar mills. Before the 1807 Act, the major invention in the sugar industry was the introduction of the three-roller vertical mill in 1449 by Sicilian Pietro Speciale. This introduction meant that the edge runner was pushed aside because the three-roller vertical mill made it possible to squeeze more juice out of the sugar cane. An edge runner is a rudimentary style of mill, composed of a grinding stone that grinds around the edge of a circular mill. However, new vertical mills pushed the second set of rollers close together to increase the pressure upon the cane after the first pass, making it far more efficient for sugar production. Figure 2 depicts an example of the vertical three-roller mill from Martinique. This type of mill was extremely dangerous to use because it could not be easily stopped, therefore, if an enslaved person’s hand followed the sugar cane into the roller there was little to be done, apart from attempting to cut it off with a cutlass (as seen in the bottom front of the image, leaning against the base of the mill) to avoid a person’s whole body being drawn into the machine. Despite the fact that this image most likely represents an idealised version of working in a sugar mill, the women have no shoes, and many enslaved people on sugar plantations experienced problems with their feet, including cuts, infections and ulcers. | |

Figure 2 – The plantation named on this postcard, Maison de la Canne, stood on the island of St. Vincent. It operates today as a museum that highlights the link between the sugar industry and slavery. Taken from its catalogue entry on the Mills Archive website (“Maison de la Canne – Conseil Regional. Un moulin à Canes aux Antilles, milieu XIXème siècle. A sugar mill in the West Indies, during XIX th century.”)

https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/postcard-of-maison-de-la-canne-martinique-2

| Jude’s reflections on the project ‘I can honestly say this has been a formative experience. It has given me the opportunity to examine and share a part of history that is deeply troubling as well as immensely relevant to our lives nowadays. To join the two realms of sugar milling and Caribbean slavery has presented an important opportunity to study both areas from different directions and gain a deeper understanding. ‘In terms of my personal development, I have had the chance to explore different areas and job roles in the heritage sector and it has definitely given me a lot to think about. It has further invigorated my desire to work in curatorship in the future and I cannot thank Liz and everyone else at the Archive enough for taking me under their wing and giving me this fantastic experience during possibly the most seminal period of my academic life.’ | |

We welcome your comments and feedback on this exhibition, as well as your suggestions for future exhibitions.