‘His motives were purely those of revenge, but now being about to die, he desired to make what reparation lay in his power.’

This Gem, an article from the 11th January 1899 edition of the Northwestern Miller, describes a hermit miller.

‘Although far advanced in years, Mrs. Bailey is an active woman, and attends to the duties of the mill with only the assistance of a half-grown boy.’

Despite this positive introduction, a tragic story lies behind this hardworking miller.

Mrs Winifred Bailey grew up the daughter of a miller. She was ‘an unusually pretty girl, industrious, modest and amiable’. She was promised in marriage to Stephen Letton, but in the summer of 1836, she met and fell in love with a Thomas Bailey. Her betrothal was broken off with Letton, which we can imagine might have caused quite a disturbance in their community, and she married Thomas. However, in an unexpected turn of fate, Letton and the Baileys remained friends.

A few months after the marriage, both Stephen Letton and Thomas Bailey had to take business trips at the same time and so travelled together for the first part of their journies. Before they went their separate ways they lodged with a friend of Bailey’s, where Letton borrowed a large sum of money from Bailey, promising to pay it back. This is where things started to go wrong:

‘The night following Bailey’s departure from the drover’s house, it was entered by an assassin who killed the inmates and secured a package containing $1,800 in bank notes.’

Police recovered a bloodstained wrapper from the scene of the crime.

Meanwhile Bailey, who was unaware he was now the prime suspect of a murder investigation, received a package upon returning home with the money he was owed by Letton. The police shadowed Bailey for the next four months, checking every banknote he spent.

‘Finally the shadowed man paid over a twenty-dollar bill, which had a red mark in one corner.’

The police matched this to the bloodstained wrapper and despite Bailey pleading innocence, he was sentenced to a lifetime in prison. After serving only ten years of his sentence he died of consumption.

But this was not the end of the tale! Winifred had always pleaded her husband’s innocence, and what happened next would confirm her conviction:

‘A few years after the death of her husband, Mrs Bailey received a letter bearing the post-mark of San Francisco. It was signed by a notary public, and a minister of the gospel, and the contents were remarkable, to say the least.’

In it was a deathbed confession. Letton, who was presumed to have been killed on the night of Bailey’s supposed murders, had actually been fatally wounded in a bar brawl. Seeking revenge for the breaking off of the betrothal, he had set up the whole incident so that Bailey would be convicted.

‘His motives were purely those of revenge, but now being about to die, he desired to make what reparation lay in his power.’

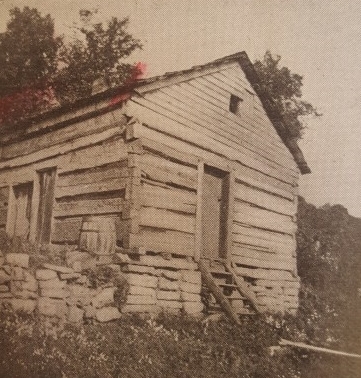

‘Shortly after this Mrs. Bailey’s parents died. Having spent her means in her husband’s behalf, she gave up everything but the old mill and the log cabin, to which she retired to finish her days in solitude.’

Gem from the Northwestern Miller 11th January 1899

Related links

- A widow’s work: Women who have kept mills alive following their husband’s death

- She’s a Jolly Miller: Mrs Bailey isn’t the only widow who ended up running a mill by herself. Click here to find out about Mrs Dickinson, known for her beaming smile.

- The crucial role women have played in milling.