Watercolours

The ancestor of what we would recognise as watercolour was developed in the Medieval Period. It was called gouache, which is French for ‘body colour’. This would be a mix of coloured pigment with water and a white produced with either chalk, lead or zinc oxide. This creates a bold colour and was used for illustrating religious documents such as bibles and psalters.

The 17th Century would see the development of what we would now recognise as watercolours. Pigment dissolved in water would be applied to a surface, when the water evaporates it leaves a mark. This creates a translucent effect which allows light to reflect from the surface below. Advances in paper production in the 18th century would spark the Golden Age of watercolours, which would last until the mid-19th century. The likes of J. M. W. Turner would push the medium and introduce larger and more ambitious watercolours. Yet the standard art societies of the time still favoured oil paintings so watercolourists would form the Society of Painters in Watercolours in 1804 and the New Water Colour Society in 1832.

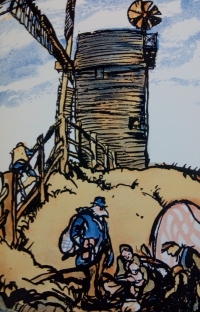

Watercolours were particularly suited to the landscapes of the Romantics. Not only were the materials easy to transport to locations. By using a freer brushwork and more textured paper they were able to create new effects, capturing fleeting atmospheric effects and evoking a sense of emotion and storytelling so loved by the likes of the Pre-Raphalite Brotherhood. This more natural looking images had already made the medium popular for depicting plants and animals, but now it was turned to rural settings including mills.

Watercolours themselves developed throughout the Golden Age, beginning with the introduction of small hard cakes of water-soluble colour invented by William Reeves in 1780. The artist would mix these cakes with water in a small porcelain dish or an oyster shell. 1846 saw the introduction of moist watercolours in metal tubes.