Post-medieval mills and milling, 1540-1750

The period between the end of the 16th century and the start of the industrial period in the mid 18th century is one marked by new ideas and significant developments, both in technology of corn milling and in the nature of trade. Changes in land ownership after the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid 16th century, coupled with a rise in population as standards of living improved during the late Tudor and Stuart eras, put new pressures on natural resources. This included water courses, where there was a demand from a growing number of trades and industries that required power, including metal working and paper making.

Suit of mill (tenants having to use the mill owned by their lord), however, was still important at the start of the post-medieval period. In Halifax parish several new mills were built to compete with the manorial mills between 1558 and 1640. In some cases they were suppressed by the courts, following action by the lord, but others survived. Some lords also built new mills alongside older ones, to cope with increasing business, although there was a growing dissatisfaction with the obligation to do suit and the lack of commercial competition.

Enforcement of suit of mill seems to have become increasingly difficult and by 1750 its influence had diminished considerably, particularly in the south and east of England, although it remained strong in the south-west, Wales and the north of England, especially Yorkshire, and in Scotland, where it was known as thirlage, into the 19th century. While it was usually the miller who benefitted directly from the amount of multure taken, it was the landlord or mill owner who dictated the rent charged for the mill.

Before the end of the 16th century there is evidence of improvements in mill gearing, which enabled two pairs of millstones to be driven by a single waterwheel. Described as treble gear, the arrangement was a large diameter pair of millstones driven directly from the pitwheel and a short layshaft driven off one side of the pitwheel, with a second pair of gears to drive a second pair of stones of lesser diameter. Because of the additional gearing, the runner of the second pair of stones was faster rotating. In the 1590s a watermill at Sidmouth, Devon was described as a ‘treble mill’ with a waterwheel driving two pairs of stones, one for clean corn and the other for malt. It was further noted that there was insufficient power to run both pairs of millstones at the same time.

Similarly in 1649-50 Mildenhall Mill at Claines, to the north of Worcester, was described as three mills for grinding several sorts of corn, although they could not all be worked at the same time ‘the stream being small’. The so-called treble mill gearing became more widespread during the 17th century, although it was not illustrated until the early 1720s.

There are also numerous references throughout England to multiple mills, as for example at Langacre, Broadclyst, near Exeter, which was described as three grist mills and a malt mill under one roof in 17th and early 18th century leases. It is probable that each ‘mill’ still meant a waterwheel, pair of gears and pair of millstones, as in the medieval period.

The Town Mill at Lyme Regis, Dorset, which was rebuilt after being destroyed by fire in the siege of the town in 1644, during the Civil War, had two waterwheels each driving a pair of millstones in 1675; in 1728 a ‘treble malt mill’ was added. The use of conventional millstones to grind malt was gradually superseded by pairs of iron rolls, as a granular rather than a finely ground product was required. Survival of a treble mill layout is extremely rare, one of the last complete examples being Arden Mill, a small estate mill in a remote location in the North York Moors.

Where there were two or more mills under one roof, the waterwheels that drove each pair of stones could be located side by side in a central wheelpit, at both ends of the building or in line, either one behind the other, or partially overlapping. Mills with two overshot wheels in line were once common in the south-west and north-west of England and also in Scotland. Such an arrangement was often superseded by a single, larger diameter, wider wheel as, for example, at Town Mill, Lyme Regis in the early 18th century and also at Sheffield Mill, Fletching, East Sussex. Larger waterwheels were required to provide sufficient power to run two or more pairs of millstones, usually through spur gearing which, by the mid 18th century, dominated gearing layout in both watermills and windmills.

Spur gearing, with a vertical shaft carrying a large diameter horizontal gear wheel from which drives were taken by small gear wheels (stone nuts) to millstones or ancillary machinery, is illustrated in late medieval sources, but probably only became a practical reality in the 17th century.

One of earliest surviving examples is the unusual stone tower mill at Chesterton, Warwickshire, which dates from 1632. Its two pairs of millstones mounted on a table hurst are now driven from below (under-driven) but they were possibly originally over-driven with the spurwheel above the millstones. An advantage of spur gearing was that the millstones ran at the same speed and their diameters could be standardised within each mill. Interestingly, larger diameter stones tend to be found in mills in the north of England. Spur gearing was to become particularly well suited to the circular multi-floor plan of tower mills, allowing two, three and sometimes more pairs of stones to be grouped around the central shaft.

Heron Corn Mill, Beetham, Cumbria, represents an interesting regional type of watermill. Rebuilt in about 1740 as an oatmeal mill, it has four pairs of millstones under-driven by spur gearing from a single waterwheel, with ancillary equipment and a kiln for drying the oats prior to shelling and grinding. The millstones are set on a free-standing hurst frame, known locally as a lowder.

The periodic rebuilding of both watermills and windmills, made necessary due to the stresses and strains of working in what were relatively aggressive environments, also saw a move towards the use of more durable materials such as stone and brick. Waterwheel pits, which archaeological evidence shows were often originally timber structures, or lined with timberwork, were now frequently built of stone. Stone and, later, brick built windmill towers also became more common, such as the two small stone towers at Easton on the Isle of Portland, Dorset which are marked on a chart of 1626 and the unique Chesterton Windmill, mentioned above.

The timber-framed and clad tower mill, popularly known as the smock mill, was also introduced, probably from the Netherlands, before the end of the 16th century. Initially designed for land drainage, it was quickly adapted by English millwrights to corn milling, the form becoming particularly dominant in Kent and the south-east of the country.

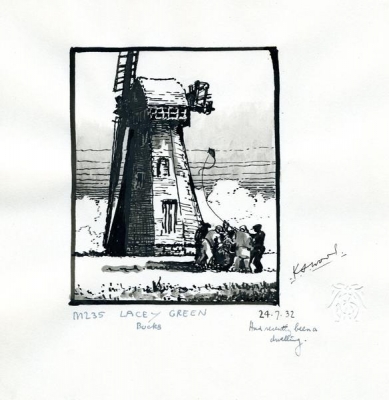

Post mills also continued to be built or rebuilt in those areas where timber-framing traditions were strong. In some post mills, such as at Cromer, Hertfordshire, where parts of the structure have been tree-ring dated, the post is older than the framing of the body, indicating that the mill has been rebuilt but that the original post has been reused. The tradition of burying the trestles and cross trees of post mills in the ground tailed off in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 18th century it became usual to build a roundhouse around the trestle, which not only protected it from the weather but also provided a convenient grain storage facility, another reflection of change in the milling trade.

Developments were also made to the gearing within post mills to enable them to drive two pairs of millstones, the stones being over-driven from the head or brake wheel and also a tail wheel mounted on the windshaft. This method of driving two pairs of stones is a form of layshaft drive, which is also found in watermills. Several attempts were made in the 16th century to establish floating or boat mills on the Thames in London, to serve the city’s growing population. Such ventures, however, proved short-lived and they were never as successful as those on the larger rivers of mainland Europe.

Millstones continued to be imported from France and Germany, as they had been in the medieval period, French burrs and lava stones, known as blues, blacks or Cullins (from Cologne, the major shipping centre on the Rhine), being particularly favoured for milling wheaten flour. In 1588/9 Ralph Sheldon of Beoley, Worcestershire, kept a pair of black millstones ‘only for the provision of my house’. ‘Common stones of the country’ were used during his absence, which he thought suitable for those who did not appreciate the fineness of bread. These black stones were used in a ‘little mill’, probably a geared handmill, a number of examples of which have survived, which appear to have been in quite common use for grinding flour and malt for baking and brewing in the homes of landowners and more prosperous yeoman farmers.

The most widespread English millstones were Peaks or grey stones, of Millstone Grit, quarried from suitable outcrops from the Derbyshire Peak District and the western and northern Pennines. Welsh stones, of sandstone conglomerate, were of more local importance, throughout Wales and also the south-west peninsula, where they appear to have been imported in increasing numbers during the post-medieval period.

By the mid 18th century most of the developments in grain milling machinery had been made. The succeeding industrial period was to see an increased sophistication applied to such developments and more scientific and technical methods applied, such as analysis of waterwheel efficiency and gearing profiles. The empirical approach of millwrights whose technology and craft skills were those developed from carpenters and smiths in the later Middle Ages, became of necessity a more technical one.

Select bibliography

- Gauldie, E. 1981: The Scottish Country Miller 1700-1900, Edinburgh, John Donald Publishers Ltd

- Harrison, J. 2005: The ‘Rise’ of the White Loaf. Evidence from the North of England concerning developments in milling technique in the eighteenth century, London, SPAB Mills Section

- Steer, F.W. 1969: Farm and cottage inventories of Mid Essex 1635-1749, London and Chichester, Phillimore

- Watts, M. 2005: Water and Wind Power, Princes Risborough, Shire Publications Ltd