Cereals and cultivation: Prehistory to the Romans

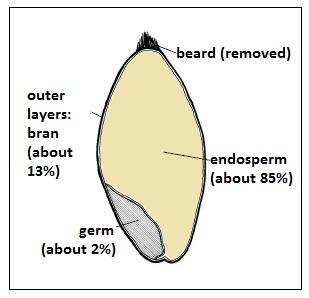

The cereal grains upon which the greater part of the world’s population depends for its daily food requirements come from plants that belong to the large family of grasses. A typical grain comprises three main parts: theendosperm, the starchy centre which is made into flour; the germ, the embryo of the new plant; and bran, the covering layers. The whole grain is rich in carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, protein and fat, an almost complete food, but refined white flour, in which the bran and germ has been removed, is mainly carbohydrate.

Today some 700 million hectares of cereals are under cultivation worldwide, a long way from their humble beginnings as wild plants whose grains were collected by local hunter-gatherer societies. The three main cereal crops are maize (Zea mays), rice (Oryza sativa) and wheat (Triticum spp.) which account for about 90% of all cereal production.

Other cereals are important on a regional basis, such as sorghum in Asia and Africa and millet in India and parts of Africa. Other lesser grown cereals include barley (Hordeum vulgare/sativum), oats (Avena sativa) and rye (Secale cereale), all crops that can flourish in cooler climates. Plants such as buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) are not strictly speaking cereals as they do not belong to the grass family. They are often, therefore, referred to as pseudocereals.

The word cereal comes from Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture. According to myth it was Ceres who first taught humans how to plough and introduced them to grain and the art of grinding. Similarly, in China, it was the legendary emperor Shennong who invented agriculture and domesticated rice and millet. In Mesoamerica, the god Quetzalcoatl, in the guise of an ant, brought the first grain of corn (maize) from the back of the mountains.

Archaeological evidence shows that emmer and einkorn (primitive forms of wheat) and barley were first cultivated in the eastern Mediterranean some 9,000-11,000 years ago. Millet and rice were domesticated at around the same time in eastern Asia, and likewise millet and sorghum in western Africa. Maize, a native plant of Mesoamerica, is thought to have been domesticated in the Tehuacan or Balsas Valleys in Mexico around 2500BC.

The change from hunter-gathering to farming in the eastern Mediterranean is recorded in the Bible. When God casts Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden he tells them that ‘Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat of it… It will produce thorns and thistles for you, and you will eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food’ (Genesis 3.17-19, NIV).

In reality, whether this conversion was due to population growth and/or climatic change is unknown. Whatever the causes, agriculture was the new order and gradually, probably through a combination of migration and acculturation, spread across Europe along with the cereals themselves, eventually reaching Britain in about 4000BC, marking the change from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic period.

Carbonised grain and grain impressions on pottery indicate that Neolithic communities in Britain (c.4000-2000BC) cultivated emmer, einkorn, barley (both naked and hulled) and also possibly bread wheat. Some regional differences are discernible with barley, perhaps because it is a hardier plant with a shorter growing season, being the prevalent crop on sites in northern Scotland.

Emmer and einkorn are hulled wheats that require further processing after threshing to remove the grains from the glumes (husks) before grinding on saddle querns. Although it is low in gluten, emmer produces good quality flour with a high protein content.

Einkorn, which is comparatively low yielding, does not produce particularly good flour and is best eaten as whole grains.

Bread wheat on the other hand is free-threshing and produces high quality flour. But it is a tender plant, vulnerable to pests and diseases and requires a more fertile soil. Consequently, it was not much grown in the prehistoric period. Both naked and hulled barley are free-threshing varieties.

Cereals were sown in woodland clearings, the ground being first tilled with a primitive form of wooden plough known as an ard. The criss-cross marks in the soil revealed beneath South Street long barrow, Wiltshire, dated 3663-3360BC, are thought to have been made by an ard. However, such cultivation appears to have been on a small scale only, perhaps to supplement wild resources or for specific social and symbolic purposes. Indeed, although the situation would not have been the same across Britain, it is thought that, generally speaking, the change from hunter-gathering to subsistence farming was a gradual process. It was not until the Middle Bronze Age (c.1600-1200BC) that farmsteads and small settlements set amongst fields became the norm and cereals became a staple food.

The main cereals grown in the Bronze Age (c.2500-700BC) were emmer, bread wheat, barley and spelt. Einkorn does not seem to have been grown much if at all beyond the Neolithic period. Like emmer, spelt is a hulled wheat with good milling qualities. Barley seems to have been particularly important, with a gradual change in emphasis from the naked to the hulled variety. It is a versatile crop, growing on heavy or light soils. It can be autumn or spring sown and, although it does not flourish on poorly drained or acidic soils, it is widely grown.

The range of cereals grown in the Bronze Age continued to be cultivated into the Iron Age (c.700BC-AD43). There appears to have been an increase in the amount of land cultivated, with expansion onto heavier soils made possible by the use of iron plough-share tips. By about 500BC emmer had been largely replaced by spelt, which became the dominant crop. This may have been due to the climatic deterioration that began about 1000BC. Emmer is vulnerable to frost but spelt is hardy to cold and wind, so seed could be sown in autumn and harvested earlier than spring sown varieties. Rye and oats were also being cultivated by the latter part of the first millennium BC. Both tolerate infertile and acid soils; oats fare better in a moist, mild climate while rye copes well with dry conditions.

Britain was described by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC as a fertile and productive island producing two harvests a year. He further noted that ‘the method [the Britons] employ of harvesting their grain crops is to cut off not more than the heads and store them away in roofed granges, and then each day they pick out the ripened heads and grind them’ (Diodorus 2.47.1, 5.21.5). However, where ground conditions were suitable, grain could be also stored in underground pits. Although saddle querns were still in use, most grain would have been ground on rotary querns which were introduced c.400BC.

The predominance of grain-rich soil samples from sites in the southern Britain has led to the suggestion that a surplus was being produced. This was perhaps consumed either as food or drink in communal feasts held within the hillforts that dominated the landscape and/or traded. Writing at the end of first century BC, the Greek geographer, Strabo lists grain among Britain’s main exports at that time (Geography 4.5.2).

The Roman period (AD43-410) saw great changes in the British countryside, particularly in central, southern and eastern England with the development of large villa estates. The presence of large granaries at villas such as Lullingstone, Kent and of watermills at Haltwhistle Burn Head on Hadrian’s Wall and Fullerton in Hampshire, for example, suggest that more grain was being processed than ever before. The foundation and growth of towns created a demand for agricultural produce and the Roman army also generated a huge requirement for grain, each soldier consuming about a third of a ton (c.340kg) a year. The majority of forts had at least two granaries (horrea) where large quantities of grain and other goods could be stored.

The carbonised grain found on many sites across Britain shows that the main crops continued to be spelt, barley and bread wheat. The Romans are also credited with introducing oats into Scotland. Interestingly, it seems that grain was also imported, at least in the early Roman period. The small amounts of einkorn, lentils and bitter vetch in a large deposit of carbonised grain found in a shop close the forum in London which was destroyed by Boudicca in AD60, suggest that it came from the Mediterranean or even the Near East.

By the third and fourth centuries AD improved types of plough that could turn heavier and deeper soils were being used, which enabled even more land to be put to arable use. By the end of the Roman period bread wheat had become the dominant crop over much of the country. This was probably due to a combination of reasons: the cultivation of heavier soils coupled with the availability of resources to ensure programmes of manuring and weeding to produce the fertile soil it required and the fact that it is a free-threshing wheat and therefore, easier and cheaper to process.

Select Bibliography

- Fairbairn, A.S. (ed.) 2000: Plants in Neolithic Britain and Beyond, Oxford, Oxbow Books

- Reynolds, P.J. 1979: Iron-Age Farm: The Butser Experiment, London, Colonnade Books

- Brears, P, Black, M., Corbishley, G., Renfrew, J. and Stead, J. 1993: A Taste of History: 10,000 Years of Food in Britain, London, British Museum Press

- Brown, A. 2007: Dating the onset of Cereal Cultivation in Britain and Ireland: The Evidence from Charred Cereal Grains, Antiquity, 81, 1042-1052

- Jones, M. 1981: The Development of Crop Husbandry. In Jones, M. and Dimbleby G. (eds), The Environment of Man, BAR British Series, 87, 95-127

- Veen M. van der and Jones, G. 2006: A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age, Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15, 217-228

- Thomas, J. 1999: Understanding the Neolithic, London, Routledge

- Price, T.D. (ed.) 2000: Europe’s First Farmers, Cambridge University Press

- Dark, P. 2000: The Environment of Britain in the First Millennium AD, London, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd