by Elizabeth Bartram

If you read about climate change and potential solutions to crop growing, you might have heard of ‘sorghum’ already. You will also be more or less familiar with the grain and feed crop depending on where you live in the world. Described as an ‘ancient grain’ (https://www.buhlergroup.com/global/en/industries/Wheat-and-grain/Sorghum.html), varieties of sorghum are indigenous to parts of Africa and North America where it is well-suited to a climate that is hot and dry.

During the 21st century, there have been discussions about the increasing potential of sorghum growing in parts of Europe where temperatures are climbing and negatively affecting some of the traditional crops grown there.

Search for sorghum online and you will find claims that it is a nutritious and healthy food option, that it is cheaper than wheat and the fifth most important grain in the world (after maize, rice, wheat and barley). It has a variety of uses, from animal feed and biomass, to different products for human consumption.

Like so many things, history shows a long period of trial and error, or hardship and perseverance, to produce varieties of crop that some of us can now take for granted. Here are some extracts from a fascinating article written in 1937 by John A. Bird and published in The Northwestern Miller, a newspaper produced for people working in the United States milling industry. To read the full issue, preserved and digitised by The Mills Archive Trust, click here.

Plant-breeding pioneers in the USA, late 1800s – early 1900s

Entitled ‘Plant Breeder’, the article covers in great detail the achievements of an American plant breeder/agronomist called Dr John H. Parker. Much about his efforts to improve wheat varieties is included, but the article begins with his work with sorghum.

Bird describes Parker as

‘a man who builds new crops to the exacting measure of this drouth-ridden [drought-ridden], wind-swept Great Plains country. While engineers are streamlining autos and planes and trains, John Parker is streamlining forms of plant-life, taking old and inefficient types and redesigning them for the strenuous plains’ climate, the machine age, and the modern consumer.’

John A. Bird, The Northwestern Miller, 1937

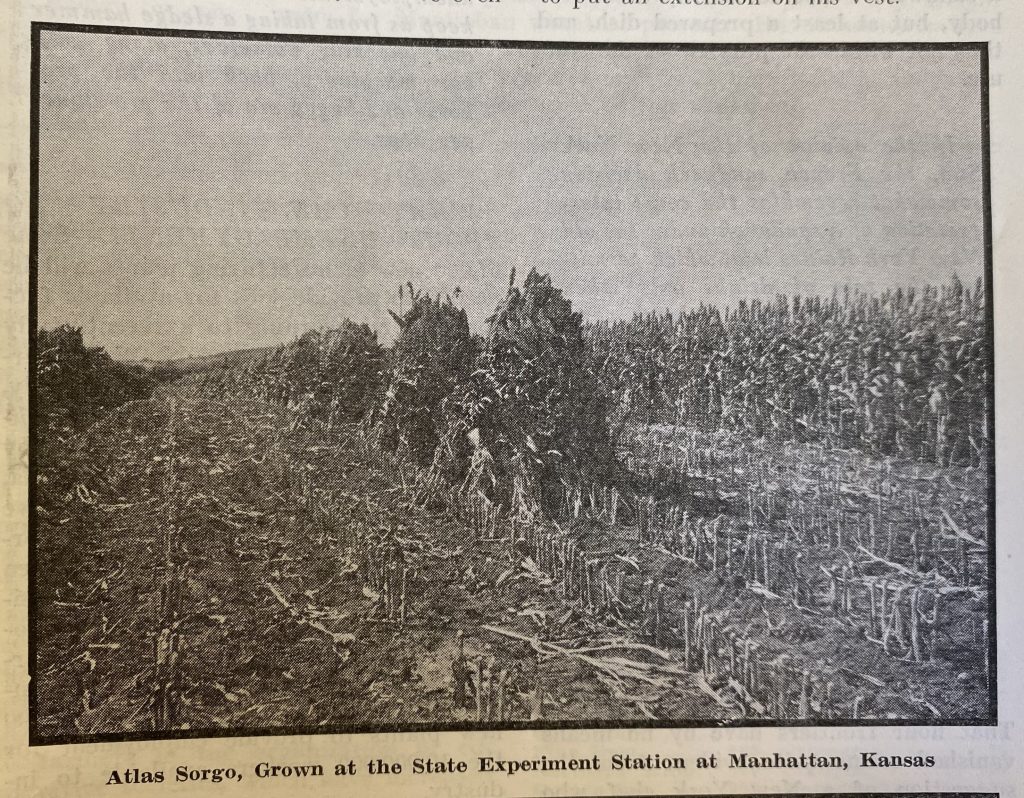

One of Parker’s varieties of sorghum, called ‘Atlas’ due to its strength, became the ‘hero’ during the drought affecting the Great Plains in the summer of 1936. Corn (maize) struggled in the hot, dry and windy conditions, burned and eaten into the ground by plagues of grasshoppers and chinch bugs. In contrast we are informed that Atlas, although stunted, grew ‘green and whole, seemingly impervious to the terrific, blasting heat, and the hordes of grasshoppers and sucking chinch bugs.’ During that year, Atlas ‘provided feed and grain for those farmers lucky enough to have it on their land.’

Going back a stage, we are informed that the sorghums available in the United States were not immediately ideal: those with juicy stalks necessary to tempt cattle and pigs had a grain that was bitter and unpalatable, whereas those with palatable grains had a dry stalk. As a result, ‘many farmers who should be using sorghums as a protection against drouth were tempted to take a chance with corn. Too often they were caught short – and that meant heavy losses, uncertainty.’

This is where another person enters the stage. I. N. “Newt” Farr was a farm hand who in 1916 began to consider how to improve sorghum. Borrowing plots of land from farmers (Newt is described as a ‘Socialist of strong convictions and [who] didn’t believe in private ownership of land’), he began to experiment. In his own words, Newt was trying to breed a sorghum that was

‘Tall. Sweet. Juicy stem… Nice tasting white seed… Strong stalk, able to bear up in our winds’.

Despite his ‘homemade’ education and lack of knowledge of genetics, he found a hybrid of sorghum growing that appeared to be a cross between two types of sorghum. He recognised its potential and ‘treasured the seed until planting time’, when he then sowed it in his borrowed plot of land. Over several years he experimented with it until, satisfied, he sent the seed to a branch experiment station based in Hays, Kansas.

Now Hays we are told is situated far to the west and at a higher altitude than the area in which Newt was working, and so the hybrid did not do so well. Fortunately, John Parker himself saw the struggling specimen and recognised that it could thrive in a different set of climatic conditions. So off to eastern Kansas he went, taking the hybrid with him. It took another ten years for the new variety of sorghum to become ‘uniform and stable,’ at which point in 1928 it was made available to farmers and ‘was ideal.’

Another article about plant breeding (covering corn, oats, barley and alfalfa), also published in the Northwestern Miller in 1937, refers to sorghums as

‘the “corn” of central and western Kansas, because of their drouth resistance and ability to stay green and wait for rain during the dry, hot months of July and August. After the rains of late August or early September the sorghums resume growth and produce a fair crop of feed, and in some cases grain. Under the same conditions corn literally dries up and blows away.’

This article goes into more detail regarding the varieties of sorghum grown in the USA and their particular qualities and provides an overview of the development in plant breeding. The author also mentions Newt, though refers to ‘This “agricultural scientist”’ as a farmer. Atlas became the variety with the most potential following many experiments with further cross breeding of Newt’s initial seed. In 1937 it was ‘the most widely grown and popular variety of sorghum in eastern Kansas’ and was also grown in part of Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa and Wisconsin. We are also told of another variety called ‘Wheatland’ – cultivated in such a way that it was ideal for combine harvesting – bred by J. B. Sieglinger. One of the early plant breeders was another Kansas farmer called J. N. Freed, who in his crop improvement ‘hobby’ was producing and growing ‘a very early drouth resistant variety known by his name, Freed.’ Even this variety was later cross-bred with another sorghum to create Greeley sorghum, well adapted and ‘well liked by farmers.’

Sorghum for a sweet tooth

The Northwestern Miller gives further insight into the uses of sorghum, in a 1938 article interestingly entitled ‘Ghosts of Mills.’ The author, C. C. Isely, looks further back, starting in 1886 when a blizzard ‘wiped out herds of cowmen.’ Then came the settlers and homesteaders who established themselves across the whole of western Kansas:

‘Magic towns with broad avenues sprang up. Then men found that Illinois corn was not suited for raising in these highlands.’

And so, sorghums were grown as they were most resistant to drought than corn. Without ‘sugar maples’, sugar cane or sorghum could be used to make a sort of molasses and Isely writes that ‘many a hungry youngster satisfied his appetite for sweets with cane syrup spread on corn bread or mush.’ In the township of Ford, Kansas, a mill was to be built. A sugar mill. Isely recalls that

‘even in northeastern Kansas there was a neighbourhood sorghum mill and the word sorghum had a good sound, to say the least, and the rich brown molasses wasn’t bad when mother made hot buckwheat cakes.’

While some local communities decided to build sugar mills, we are told that a number found that it was a poor substitute for sugar and so more flour mills were built instead, including the intended sugar mill in Ford, which was ‘much more sensible and practical anyway.’

Sorghum in the 21st century

Nowadays, sorghum continues to be an important crop grown for both animal and human consumption around the world, with the USA remaining one of the largest producers. It is the fifth most important cereal and is catered for by leading mill machinery manufacturers such as Bühler, a Swiss-based engineering company with an increasing focus on sustainability and food systems resilience. They have a section on their website devoted to showcasing their expertise in sorghum milling, which includes the statement ‘Revival of an ancient grain’ (https://www.buhlergroup.com/global/en/industries/Wheat-and-grain/Sorghum.html).

According to Bühler, sorghum has been harvested for many years in places like Africa, Asia and America, while it remains ‘relatively unknown in Europe’, and it is due to its ‘ability to cope with drought and high temperatures’ that it is the world’s fifth most important crop. Its popularity has also been supported by growing trends in gluten-free foods, of which sorghum is one.

There is an annual international sorghum conference organised by several agricultural research institutions (https://www.21centurysorghum.org/). Central themes emerged out of their 2023 conference:

- The effect of climate change on driving the need for resilient and drought-tolerant crops, of which sorghum is one (it’s a ‘resilient, heat tolerant and water smart cereal crop’);

- The swiftly changing climates requiring faster and more responsive plant breeding;

- The opportunities for sorghum in Europe and the need for ‘active research collaboration between Europe and Africa in sorghum production and utilization to foster innovation and facilitate adaptation to diverse contexts’;

- The value of sorghum with regard to global consumption and dietary needs;

- The need to focus on crop innovations and ‘sustainable intensification’ to further enhance sorghum’s offering in diverse environments.

As of 2022, the largest world producers of sorghum were Nigeria and Sudan, followed by the USA, Mexico, Ethiopia, India, China and Brazil. Data also exist for sorghum production in 1961 and when comparing the two years, the biggest changes include in Brazil which increased production from 5 tonnes to almost 3 million tonnes (https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production).

Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado and Max Roser (2023) – “Agricultural Production”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production’ [Online Resource]

According to one source, this increase in sorghum production in Brazil is due to climate change, which has brought hotter and drier conditions particularly to central Brazil. Embrapa researcher Cicero Menezes is quoted as saying that sorghum’s tolerance to lack of water is the main attraction, as during dry periods it ‘stops its growth and grows again when the rain returns… with little compromising production’ (Sorghum is growing as an alternative for safe grain production – Revista Cultivar). When grown in succession to summer crops, sorghum also helps to keep grain costs down for the feed agroindustry. Growing sorghum in the archives

Growing sorghum in the archives

At the Mills Archive Trust, we currently have holdings on sorghum across our archive and library: most mentions that we know of so far are to be found in our digitised issues of the Northwestern Miller journals, followed by several library entries which include digital articles from the Milling & Grain magazine, and a book on ‘Sorghum Production and Utilization’ published in 1970. We are keen to analyse our holdings in more detail to identify important subjects such as sorghum, such as by indexing more of our journals more fully, but this requires a lot of effort and depends on funding to bolster our work.

As climates continue to get hotter and drier in parts of the world, including in Europe, perhaps it is fair to assume that the Trust will receive increasing amounts of material relating to sorghum as time goes on. As the guardians of the history of humanity’s efforts to feed the world, we would certainly welcome more of such material, along with additional support to highlight and explore the role of such grains and the communities responsible for their growth.