This exhibition sheds light on the links between technological developments in sugar milling and enslaved women’s reproductive systems, especially in the early nineteenth-century before the abolition of slavery. The exhibition uses images from the Caribbean islands from the period of slavery and beyond in order to map the transition of both women and machinery from ‘disposable’ to ‘vital’ in the eyes of enslavers.

‘Sugar & Slavery: Reproductive Mills’ is a digital exhibition funded by the University of Reading’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities (UROP) programme. It is written by Jude Reeves, a second year undergraduate in the Departments of History and English, with the assistance of Emily West (Department of History) and Liz Bartram (Director of the Mills Archive). The student placement has been funded by the University of Reading’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities (UROP) programme, with additional funds from the Garfield Weston Foundation to create the digital exhibition.

Share This

This exhibition sheds light on the links between technological developments in sugar milling and enslaved women’s reproductive systems, especially in the early nineteenth-century before the abolition of slavery.

This exhibition uses images from the Caribbean islands from the period of slavery and beyond in order to map the transition of both women and machinery from ‘disposable’ to ‘vital’ in the eyes of enslavers.

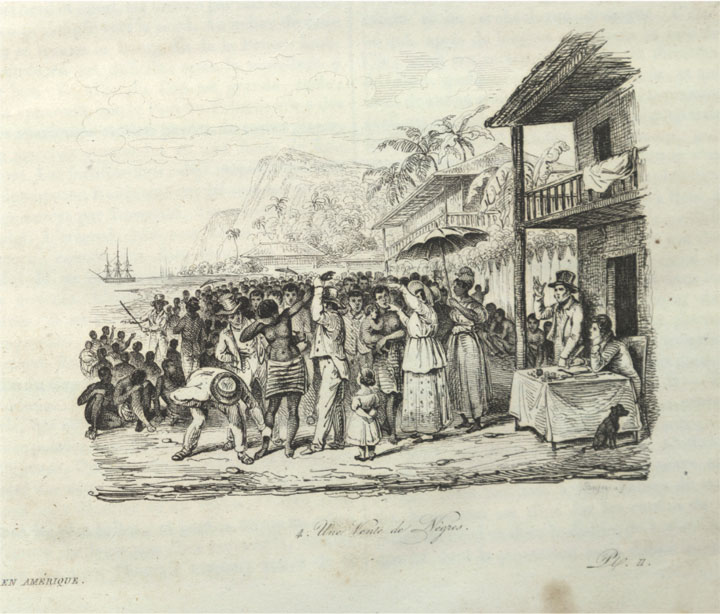

1807 saw the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, making the importation of enslaved Africans to British colonies in the Caribbean illegal. This meant enslavers were now unable to purchase new people from Africa, only those already in the colonies could be traded. When it was voted upon in Parliament, the Act passed with forty-one to twenty votes in the House of Lords and one hundred and fourteen to fifteen in the House of Commons. After decades of campaigning, it was finally illegal to export human cargo across the Atlantic, although trafficking between the Caribbean islands continued until 1811. (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/abolition.htm )

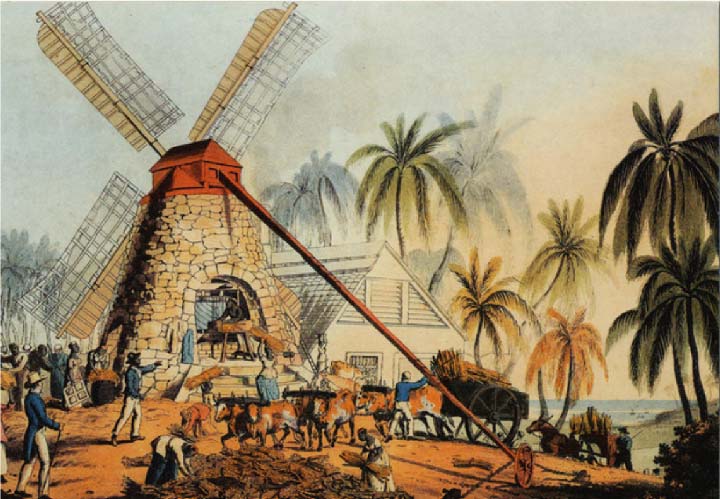

Figure 1- Displaying the intensity of the process of producing sugar in British Antigua. Central to the image is the windmill which encloses a vertical roller through which sugar cane is being passed to extract the juice to make sugar as we recognise it. This image comes from ‘Ten Views in the Island of Antigua’, Published 1823 by William Clark. These images are very important for telling us about the process of sugar milling, but we must be aware of the idealised version the images project. http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1142

After the 1807 Act, enslavers on British Caribbean islands faced the reality that their enslaved workers were no longer so easily replaceable. Instead, maintaining a population of enslaved people required more consideration by enslavers towards reproduction on their plantations as a means of ensuring profitability on sugar plantations. Planters desired maximum efficiency from their sugar machinery and to generate the next generation of slaves to preserve the future of their plantations. Moreover, the process of industrialisation in Great Britain and the adoption of technological innovations on Caribbean islands meant that this prioritisation of enhancing economic efficiencies on plantations was possible in a way that had never been seen before. Overall, then, the early nineteenth century saw some changes in slaveholders’ attitudes towards women’s fertility as well as heightened financial investment in sugar-producing machinery upon plantations.

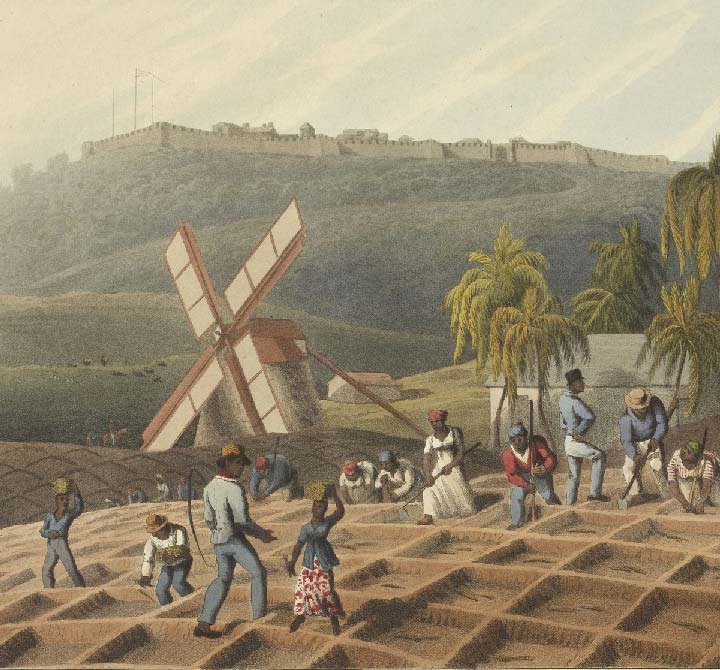

Figure 2 – Ten Views in the Island of Antigua, in which are represented the process of sugar making, and the employment of the negroes. Detail from a larger image by William Clark, 1823. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slaves_working_on_a_plantation_-_Ten_Views_in_the_Island_of_Antigua_(1823),_plate_III_-_BL.jpg

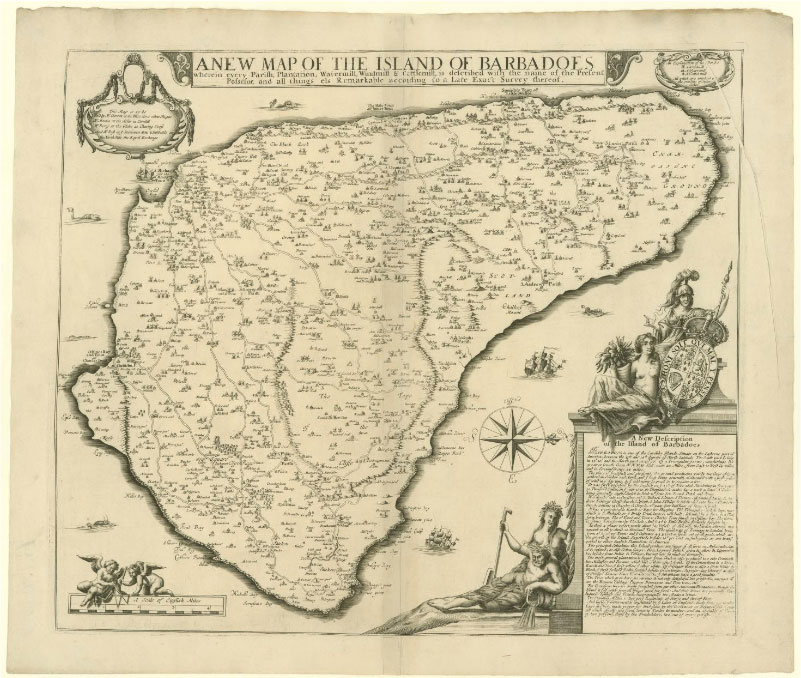

From the perspective of British slaveholders, Barbados was one of the most ‘successful’ examples of a sugar island in the period of slavery. It was covered from coast to coast with plantations almost exclusively producing sugar from the 1650s onwards. The map (figure 3) displays the extent of sugar milling in Barbados and the reliance upon sugar mills for the local economy.

Figure 3 - A Map of Barbados, created 1675 https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/JCBMAPS~1~1~1133~100880001:A-New-Map-of-the-Island-of-Barbadoe

This map displays the type of mill used at each sugar plantation. In 1675, when the map was created, windmills remained the most popular form of milling.

In the period prior to emancipation, slaveholders commonly favoured enslaved labour over machinery as the force driving efficiency on sugar plantations in the Caribbean. However, following the abolition of the international trade in enslaved people in 1807, as the region moved towards emancipation, planters began to invest more heavily in their machinery on sugar mills.

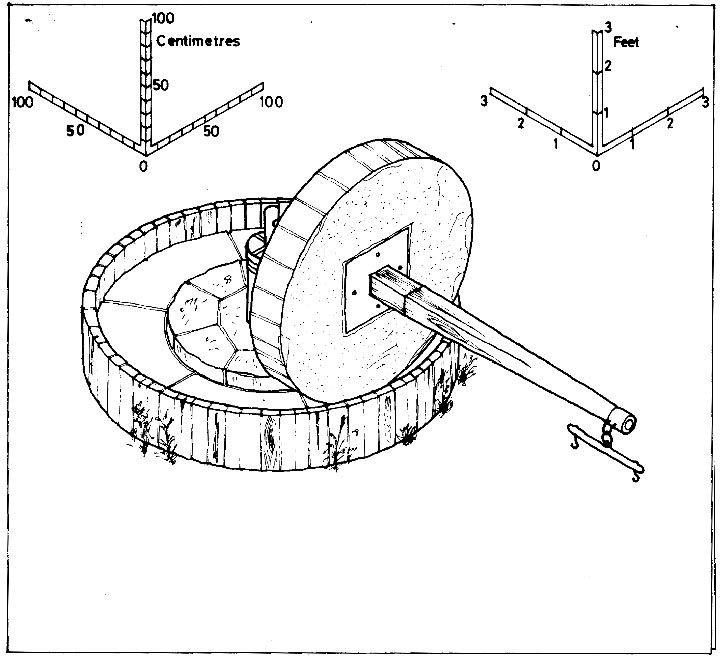

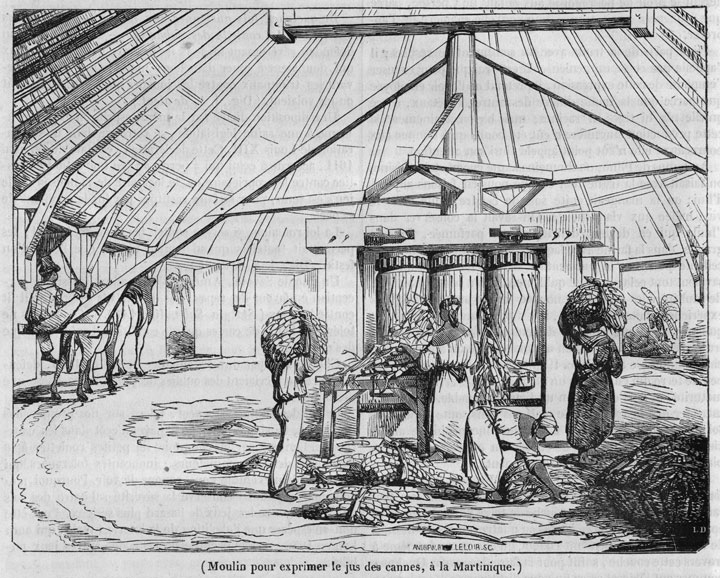

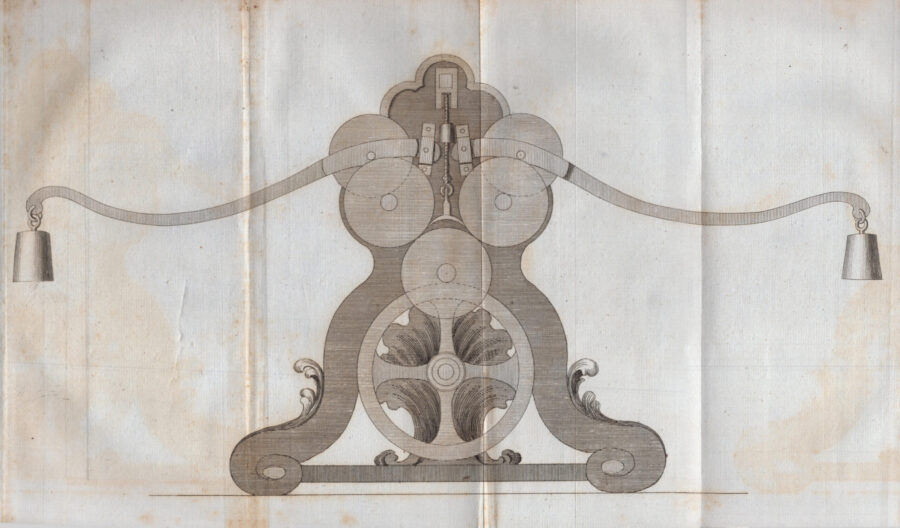

Before the 1807 Act, the major invention in the sugar industry was the introduction of the three-roller vertical mill in 1449 by Sicilian Pietro Speciale. This introduction meant that the edge runner was pushed aside because the three-roller vertical mill made it possible to squeeze more juice out of the sugar cane. An edge runner is a rudimentary style of mill, composed of a grinding stone that grinds around the edge of a circular mill (as seen in Figure 1). However, new vertical mills pushed the second set of rollers close together to increase the pressure upon the cane after the first pass, making it far more efficient for sugar production.

Figure 1- Diagram of an edge runner from the Mills Archive Trust, 1964 https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/river-barn-bucklebury-roller-mill

Figure 2 depicts an example of the vertical three-roller mill from Martinique. This type of mill was extremely dangerous to use because it could not be easily stopped, therefore, if an enslaved person’s hand followed the sugar cane into the roller there was little to be done, apart from attempting to cut it off with a cutlass (as seen in the bottom front of the image, leaning against the base of the mill) to avoid a person’s whole body being drawn into the machine. Despite the fact that this image most likely represents an idealised version of working in a sugar mill, the women have no shoes, and many enslaved people on sugar plantations experienced problems with their feet, including cuts, infections and ulcers.

Figure 2 - The plantation named on this postcard, Maison de la Canne, stood on the island of St.Vincent. It operates today as a museum that highlights the link between the sugar industry and slavery. Taken from its catalogue entry on the Mills Archive website ( "Maison de la Canne - Conseil Regional. Un moulin à Canes aux Antilles, milieu XIXème siècle. A sugar mill in the West Indies, during XIX th century.") https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/postcard-of-maison-de-la-canne-martinique-2

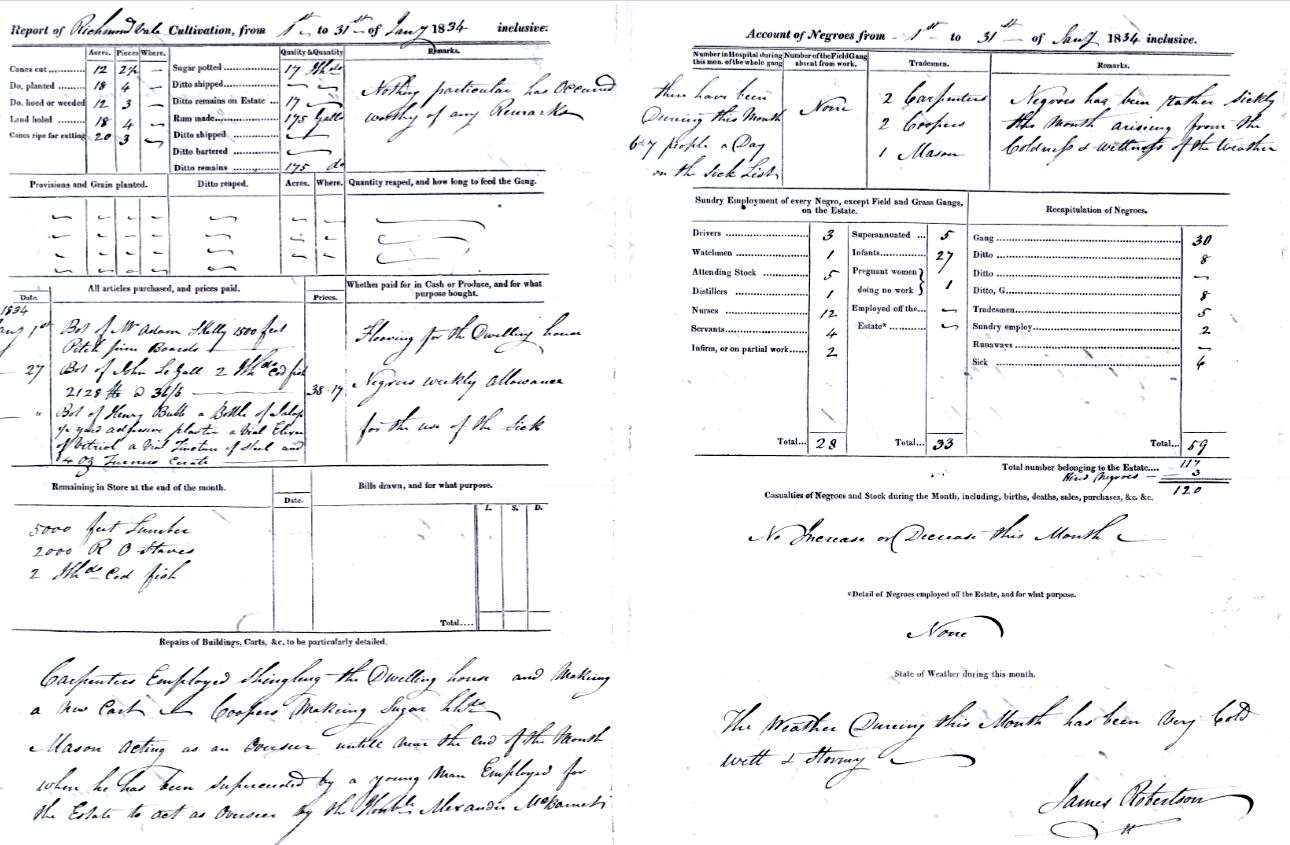

The documents shown in figure 3 form part of a report on the cultivation of sugar cane on the Richmond Vale plantation on St. Vincent. During the month of January 1834, 12 acres of cane were cut and 18 were planted. The report includes recent purchases for the sick, such as ‘a Bottle of Jalap [a purgative] ½ yard adhesive plaster a Vial Elixir of Vitriol [a tonic]) a Vial Tincture of Steel [used for skin infections] and 4 oz Turners Cerate [desiccant and astringent for ulcerations]’. Two hogsheads cod fish were purchased for the ‘negroes weekly allowance’. A hogshead was a measurement of volume usually for liquids but also for sugar, as shown in the sugar hogsheads in figure 4 (see next slide). A hogshead was the equivalent of a large barrel. For the month of January, 6-7 people per day were on the sick list – apparently the enslaved people had ‘been rather sickly this month arising from the coldness and wetness of the weather’. The report doesn’t identify individual enslaved people but does record the numbers according to age and role. For instance, there were a total of 120 enslaved people, one of whom was pregnant and not working at the time. 27 were infants, and 46 formed the field and grass gangs.

Figure 3 - Photocopy provided to the Mills Archive Trust, of a “Report of Richmond Vale cultivation, from 1st – 31st January 1834” (the original is in private hands).

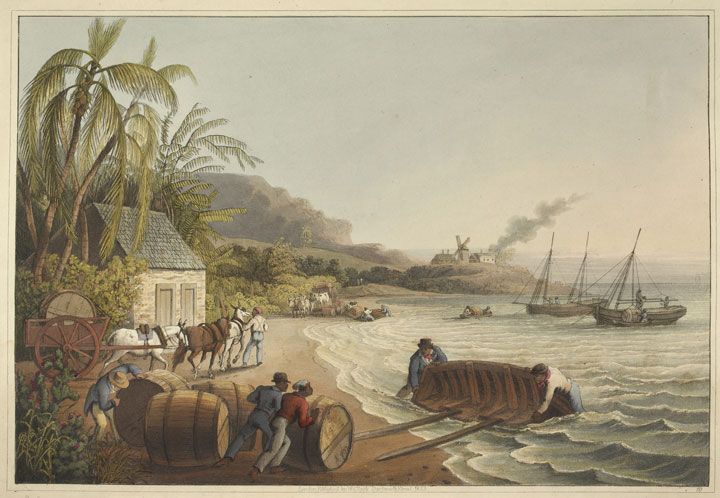

Figure 4 - Sugar-Hogsheads - Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823), plate X – depicts people rolling large barrels (hogsheads) of sugar towards a small boat, which would then carry the barrels (one at a time?) to the ships awaiting their cargo in the deeper water. From the British Library collection https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sugar-Hogsheads_-_Ten_Views_in_the_Island_of_Antigua_(1823),_plate_X_-_BL.jpg

Similar documents are lodged in other archives. Documents about the Buff Bay Plantation in Barbados detail the work and physical condition of enslaved women on this plantation (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/media/view/255 ). The sheer number of physical ailments, especially ulcers, is testimony to the difficult conditions that these women lived and worked under. It is clear that labouring on a sugar plantation was dangerous, multiple entries detail women missing limbs, most likely because they lost them to the vertical three roller sugar mill. Entries such as these convey how future innovations were needed in order to protect the enslaved people working within the mills and to maintain plantation efficiency. This seeking of economic efficiency and the pursuit of greater profit led to the introduction of the horizontal mill (figure 6), which was introduced to the Caribbean islands at the turn of the nineteenth century.

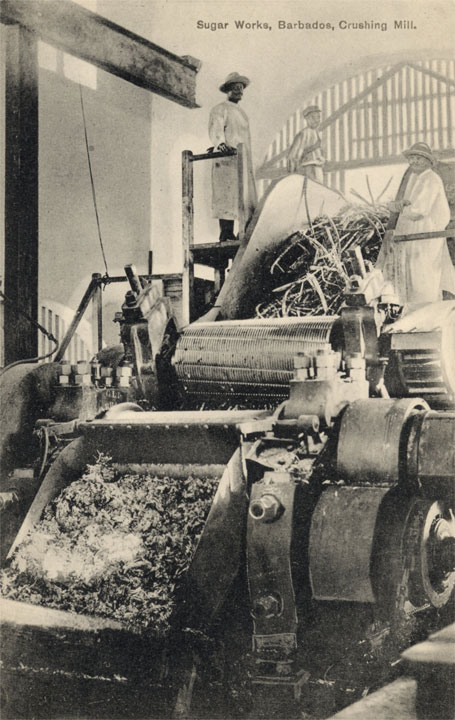

Pietro Speciale’s vertical three-roller mill experienced various innovations over time, including the move from the rollers being made of wood, to being coated in iron and then later being completely made of iron with a hollow centre. But the horizontal mill’s introduction at the beginning of the nineteenth century represented one of the most important innovations of the entire period of sugar milling in the slavery era. Using a horizontal mill made the use of a gravity chute possible, meaning it was safer for enslaved people to use and less likely to cause them injuries.

Figure 5 Moulin Bezard - Horizontal Roller Crusher - Marie-Galante (Willem van Bergen, 2000)

A gravity chute, as captured in figure 6, is a piece of wood allowing the canes to lay flat before being pushed into the rollers down the ramp. This reduced the danger of loss of limbs and made sugar milling more efficient for planters. The gravity chute meant mills lasted longer. Laying canes flat upon the length of the roller meant the whole length of the roller was utilised, and the condition of the rollers could be maintained for longer because the middle section obtained some relief from the constant bombardment of sugar canes.

Industrialisation in Europe revolutionised Caribbean sugar milling, with technological innovations increasing in the early nineteenth century. For example, the introduction of steam power led to the horizontal roller mill’s adoption more widely across the Caribbean.

Figure 6 - Image showing a gravity chute in Barbados. This was much safer it is to use as the person manning the mill is at a safe distance from the rollers. From the Mills Archive Trust (Mildred Cookson Collection) https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/crushing-mill-machinery

This image shows an example of the three vertical roller mills that could be dangerous and difficult to control due to enslaved people relying on big pieces of equipment. They were also hard to slow down on command because of the mill’s reliance on wind or cattle power. Compared to later horizontal mills, vertical mills were also inefficient, only using the centre of the roller and being dependent on outside factors to control their power, unlike later steam-engine powered mills.

Figure 7 - Slavery Images Website http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1036

Figure 8 - Sugar Mill Description of a Mill for Bruising Sugar Canes. Arthur Young, 1786, plate 3 of 3 showing rolls.

As seen in Figure 9, sugar milling increasingly adopted the techniques of production line, utilising every element of the cane, with ‘bagasse’ acting as fuel for the steam mill and other elements of the plantation both during and after the era of slavery. Bagasse is the remains of a sugar cane after the extraction of juice. Its wood-like nature meant it was a highly effective fuel and it cost nothing because it simply was a by-product of the sugar milling process. It is thought that the word originated from the Spanish word “bagazo”, which means rubbish or trash.

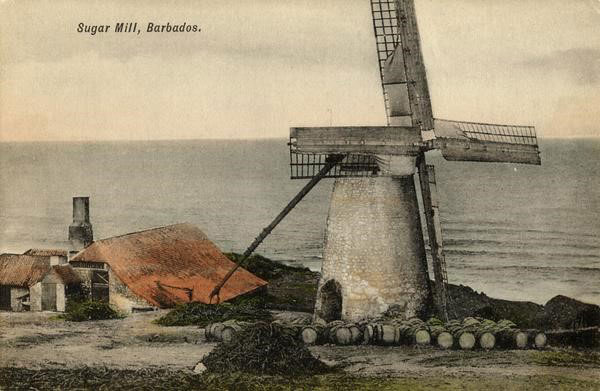

Barbados, part of the British Caribbean, emerged as the centre of sugar production in the Caribbean and indeed the world, with hundreds of mills being built there. The island’s climate and the presence of British enslavers constituted the main reasons for the prolonged success of the island as a sugar hub because these slaveholders utilised technological innovations in the sugar industry to enable more efficient production lines.

Though the Caribbean stood at the centre of the sugar trade, outside forces in Europe pushed industrial innovation and change forward in the area, selling commodities such as vacuum pans and steam engines to plantations upon the islands. The sugar plantations then raised their production efficiency, especially after the abolition of the international trade in 1807, when maintaining the safety of enslaved people as valuable commodities became more important to enslavers.

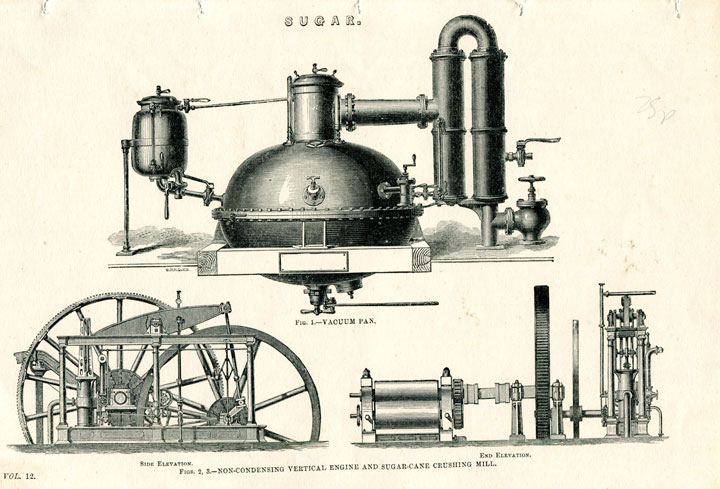

Figure 9 – The Mills Archive Trust (Mildred Cookson Collection) https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/people-feeding-cane-in-barbados

A vacuum pan (figure 10) is a piece of equipment that evaporates the moisture from the sugar at lower temperatures than normal, reducing the risk of burning the sugar crystals and making it easier to provide Europeans’ desired perfect, white crystals. Steam engine allowed planters to reduce their reliance on more natural power such as wind or animals, enabling sugar mills to run up to twenty-four hours a day, with the weather less likely to prevent the success of the day’s yield. Once cut, sugar cane deteriorates very rapidly, and inclement weather put the cane at risk of spoiling. Using the steam engine hence increased efficiency and it was also much easier to halt production using steam power, making the process safer, especially when combined with new horizontal milling techniques.

These innovations became critical to the continuation of the sugar milling industry around the time of the abolition of the international slave trade in 1807. The possibility of not being able to buy enslaved people from Africa led enslavers to become concerned about the future productivity of their sugar mills. So, they utilized technological innovations to maximise sugar milling efficiency but also to protect the value of their enslaved labour force.

Figure 10 - Diagram of a vacuum pan, undated (The Mills Archive Trust) https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/sugar-mill-machinery

Figure 11 – Postcard showing a sugar mill complex on Barbados, with the hogsheads of barrelled sugar and piles of bagasse in the foreground. Late 1800s, the Mills Archive Trust (Mildred Cookson Collection)

There are many reasons why slaveholders on the Caribbean became more invested in issues of reproduction, including their desire to generate profit from enslaved people as possessions, the value of their labour, and the fact that new generations of people would be needed to work in the sugar mills after the abolition of the international trade in 1807. Enslavers wanted to protect the size of their slave populations to ensure smooth running of their mills in the future.

Before the 1807 Act, relatively low fertility rates within enslaved communities were of little consequence or worry to planters upon Caribbean sugar islands. They were not very concerned with creating new generations of enslaved workers when they could simply buy more people imported from Africa. Indeed, slaveholders commonly lamented the time women needed to take off to bear children because this lowered women’s economic productivity in the sugar mills. Slaveholders also tended to consider enslaved children a burden before they reached an age when they could assume plantation labour. So, women often worked at their full capacity until shortly before they gave birth, and pregnant women regularly faced brutal and cruel forms of physical punishment, enacted with the same ferocity as for those who were not expecting babies. However, in the era of the 1807 Act, the reproduction of enslaved people became more important to planters.

Figure 1- Image from slavery images: http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1885 The picture displays how women were treated as property. They are being prodded and poked by prospective buyers and inspected like cattle. In the background several other enslaved people are waiting for similar treatment, with the ship that probably brought them to the island of Martinique in the distance.

In 1789, prior to the 1807 Act, Simon Taylor (seated in Figure 2) proposed buying more African women for Golden Grove, one of the six Jamaican sugar plantations he managed. Referencing “the first good Eboe ship that comes in,” he explained that he “will endeavour to get ten women out of her.” He previously valued the purchase of men more than women. For example, in 1770 he wrote: “In regard to purchasing fifteen females to five Negroes, it can by no means answer at Golden Grove, for you want men infinitely more than women, for there are many things which women cannot do.” [These quotes are taken from the article ‘Home-grown slaves’ by Sasha Turner. (Pages 39-62)]

Simon Taylor was born into a wealthy family in Jamaica in 1739. They had made their money through the sugar trade as well as other mercantile ventures. Unsurprisingly, he was against the abolition of the international trade. But because all children born to enslaved women automatically became the property of that woman’s enslaver, over time slaveholders like Taylor began to realise the benefits of gaining enslaved people via reproduction rather than through buying in additional people. By the early nineteenth century, and especially after 1807, enslavers such as Taylor increasingly took an interest in how certain punishments might affect a woman’s ability to bear children, and how best to encourage the reproduction of their slaves while still having enough women labouring on their sugar plantations at any one time.

Furthermore, as the threat of the international trade’s abolition began to loom over slaveholders, they began to focus on buying enslaved women at their peak reproductive age to attempt to ensure the next generation of enslaved workers. Over time, women who were believed to be more fertile were sold for a larger sum than those considered infertile or post reproductive age.

A horrific example of how enslavers sought to preserve women’s pregnancies can be seen through the ways in which they whipped enslaved women. Often, a hole was dug in the ground to protect and cushion the unborn child, conveying how enslavers valued their future enslaved child more than the mother.

Figure 2- Simon Taylor is seated, surrounded by his nieces and nephews, with his brother and sister-in-law standing. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_family_of_Sir_John_Taylor_by_Daniel_Gardner.jpg

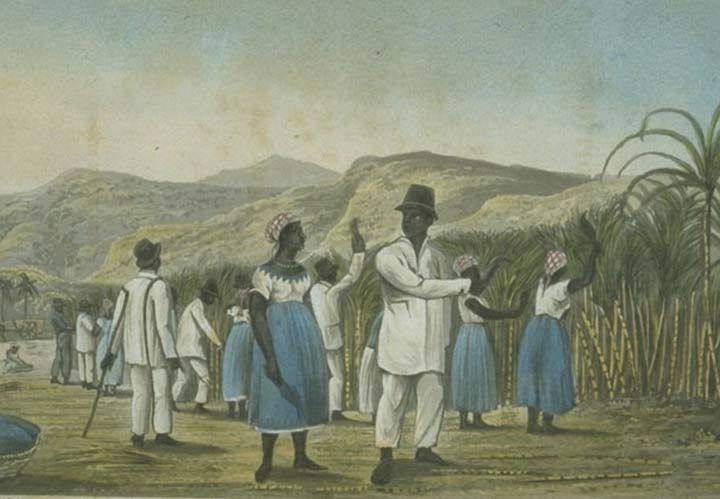

Figure 3 - Image from around 1820. This shows men and women harvesting sugar cane to be fed into the mill. While enslavers believed men to be more valuable workers, women were not excused from the heavy lifting needed on a sugar plantation. The role women played within the mill did not change that much over time: http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1111

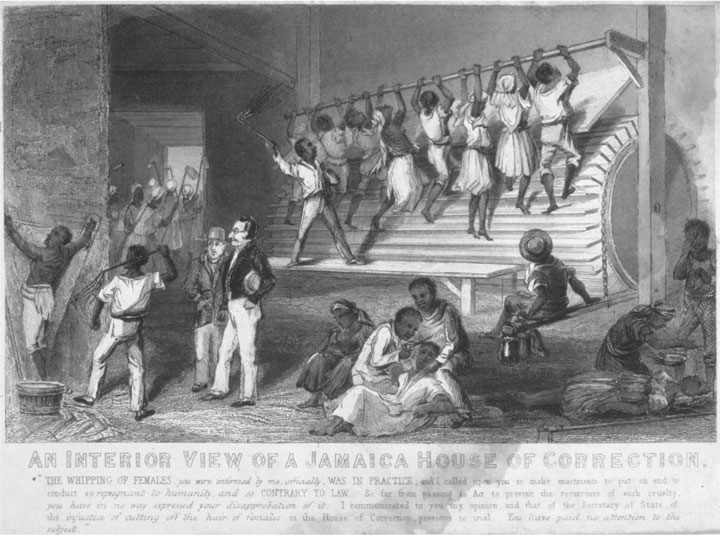

The drawing in figure 4 is from Jamaica, it shows a man being flogged to the left and in the lower centre a woman is having her hair cut off, all while white overseers are observing. On the treadmill (it is unclear whether the mill in this image is producing sugar) a black supervisor threatens the workers with the whip to ensure they work quickly and efficiently. The type of mill seen here was used in prisons in England from the start of the nineteenth century as a form of punishment which could be utilised to provide items for the running of the prison. It was also introduced in the British Caribbean. Within figure 4 is a message from Jamaica’s Governer Lionel Smith to the Jamaican House of Assembly. Smith was complaining that although such practices were illegal, “So far from passing an Act to prevent the recurrence of such cruelty, you have in no way expressed your disapprobation of it [and] you have paid no attention to the subject”.

Figure 4 - Taken from http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1297 image from Jamaica in 1837 (during the era of abolition).

Another area that conveys the ways in which enslaved women’s health was not prioritised before the threat of the abolition of the international trade loomed can be seen in diets of enslaved women. Enslaved people’s food often lacked nutrition and women commonly had deficiencies in minerals such calcium which then made pregnancy and postpartum childbearing difficult. A lack of calcium in diets, along with low iron levels, could reduce fertility and women’s ability to give birth to healthy children. While, over time, women were more likely to be given time away from their labours during their pregnancies, the nutritional needs of women were not prioritised on sugar mill plantations.

Figure 5 – Postcard showing a posed scene from the late 1800s. Although taken after slavery had been abolished, many of the people became indentured workers, whose lives were still very difficult. This image shows the workers in a sugar cane field, the majority of whom are women. From the Mills Archive Trust (Mildred Cookson Collection).

Figure 6 shows enslaved people waiting for their daily rations. The lack of full clothing is typical of the lives these women lived, often wearing cheaply-made cotton calico dresses.

Sometimes slaveholders believed that women deliberately sought to limit their fertility, so denying their enslavers future offspring. While surviving evidence is scant, some enslaved women did employ contraceptive techniques. Contemporaries sometimes accused women of encouraging miscarriages, but alternatively, these women were more likely to be experiencing the loss of their pregnancies due to dietary deficiencies and treatment of their bodies by their enslavers, for example by labouring within sugar mills throughout their pregnancies.

Figure 6 - From a Cuban plantation c.1866 http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1371

In the last few decades of slavery in the British Caribbean, slaveholders put women on lighter workloads during pregnancy and sometimes women stopped work altogether some months before the birth of their children. These changes evolved over time but grew more pronounced after the 1807 Act when reproduction became increasingly important to maintaining the enslaved population, and some of the more disposable attitudes of planters towards enslaved workforces decreased.

Figure 7- The image shows a woman in Trinidad carrying a child on her hip, created by English architect and sculptor Richard Bridgens (1785-1846). Bridgens moved with his family to Trinidad after his wife inherited a sugar plantation, where they lived for a number of years. During this time, Bridgens took note of the lives led by enslaved people. Presumably, figures such as this woman were based on those he observed at their sugar plantation http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2504

The legacy of sugar milling in the Caribbean is filled with complex issues. The islands that were most affected by both the international slave trade and the sugar industry now rely heavily on tourism for their economies. Attempting to acknowledge the past and show respect to ancestors, while still creating appealing tourist destinations to holidaymakers can be a difficult balancing act.

Morgan Lewis Windmill (see figure 1) is a fantastic example of this careful, balanced approach. It is one of two sugar mills still intact and restored and the Barbados National Trust is currently campaigning for its placement on the list of world heritage sights. The mill’s unique nature provides a draw for tourists, the guided tours focussing on milling and the technology involved. St Nicholas Abbey likewise focusses on their rum factory and steam engine as places of interest. It can be hard to convey the intensive history of the enslaved people who worked these mills and produced products such as rum and sugar, especially because surviving evidence can be very limited. However, education about colonial pasts is also important in terms of keeping the memories of those who suffered slavery alive for subsequent generations.

The David Nicholls Collection at the Mills Archive covers the many restoration works of the late David Nicholls on mills mostly in the UK but also on Morgan Lewis Windmill in Barbados in the 1990s. He conducted a survey and made a proposal for the full restoration of the only complete sugar mill in the West Indies. This led to a five-year programme of major repair works by his millwrighting company, The Chiltern Partnership. In 1995-96 David also ran the “Amy Nicholls Mill Wall Project” with the Ministry of Education, Government of Barbados. They worked with 200 schools to survey the remaining mill walls (towers) throughout the island. David’s collection provides a fascinating record of twentieth-century efforts to restore an important Caribbean monument.

Figure 1 - Morgan Lewis Windmill, Barbados, in 1990. The “outbuilding extension” at the back of the mill would have been commonly added to windmills that incorporated larger machinery as sugar technology advanced. From the Mills Archive Trust (Muggeridge Collection)

At the Mills Archive, several collections including information about Caribbean sugar mills have been donated over the years. Collections including those of Donald Muggeridge, Owen Ward, Niall Roberts, Mildred Cookson and David Nicholls show how sugar mills have been restored and taken care of over time.

Donald Muggeridge: Photos of Caribbean sugar mills from the 1980s/90s, and a collection of old and modern postcards.

Owen Ward: Notes, copies of articles and correspondence on the history of sugar milling in the Caribbean and elsewhere in the world.

Niall Roberts: Photographs of sugar mills and sugar milling machinery taken during visits to the Caribbean, with associated correspondence, notes and research.

Mildred Cookson: Mildred’s wide-ranging interests include the milling of sugar in the Caribbean, and her collection features unusual, rare and historically significant images, documents, postcards and other media.

David Nicholls: Photographs and research material from his time as a millwright in the Caribbean.

With growing interest in the history of slavery, sugar milling in the Caribbean has become more important to the archive, especially the role of enslaved people in in sugar milling processes. The Archive contains copies of documents from the 1830s on a plantation in St Vincent, including details about enslaved people’s sugar cultivation.

The project has seen the Trust’s sugar milling section of the library grow in content and almost 100 publications have been catalogued.

Figure 2 - Photograph of ruined boiling room, Annaberg, St. John 1990. From the Mills Archive Trust (Muggeridge Collection)

The responsibility to keep alive the history of enslaved people falls upon everyone. A recognition of the monumental and intrinsic role Britain played in the transatlantic slave trade and the slave regimes of the sugar industry means British people have a responsibility to recognise that history and to acknowledge our role within it. Human suffering played a part in the scientific advancements and innovations in sugar milling during the slavery era, and the Caribbean sugar trade led to products that we now use every day.

In Reading, UK we have the privilege to belong to a diverse community with people whose histories enrichen our understandings of the past and keep multiple histories alive. This exhibition hopes to show a respect for the interwoven history of people and machinery, and to acknowledge how much we owe to those who lost their freedom to the tragedy of slavery on the sugar islands of the Caribbean.

Being given the opportunity to create an exhibition which seeks to give representation in new ways to those who have been silenced has been very rewarding. It has been a fantastic opportunity to develop this project into something I can be proud of, I hope this will be a legacy I can leave at the Mills Archive.

For further information, please see the following links:

https://visitantiguabarbuda.com/destinations/bettys-hope/

Fig 3 – Ruined sugar mill tower at Brewer’s Bay, Tortola, 1989. From the Mills Archive Trust (Muggeridge Collection).