Our vision

Mills are more than historic structures. They are living symbols of our shared cultural and technological heritage. Engaging with them enriches lives, connecting past innovations with future possibilities. The preservation of both tangible (i.e. the mill structures) and intangible (i.e. archives) heritage is vital, as they are deeply woven.

Our unique role

The Mills Archive Trust is the custodian of the history of mills and milling. We safeguard the stories, skills and traditions that mills embody. Our expertise allows us to protect, interpret and open access to this rich history. Mills shaped the foundations of the modern world, and we ensure their legacy continues to inspire.

Engaging audiences

As an educational charity, we create opportunities for people to connect with the history of milling, making the past relevant to the present and future. By returning to our roots, we can deepen engagement with:

- Mills as centres of technological innovation;

- The preservation of traditional crafts, including millwrighting;

- The artistic and literary significance of mills;

- Their role as cultural landmarks embedded in diverse communities.

Collaboration and partnerships

We seek to work with other organisations that share our mission while offering complementary expertise. Together we can strengthen the protection and appreciation of mills, ensuring they continue to inspire future generations.

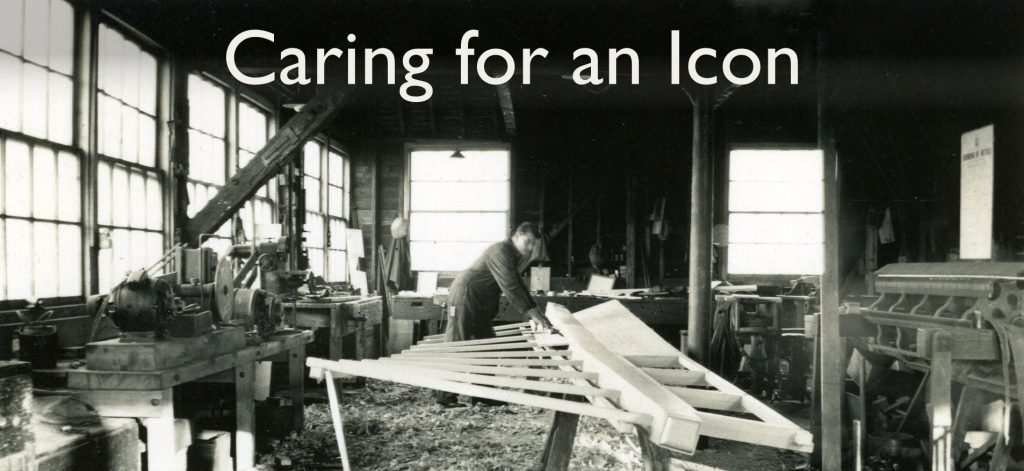

Caring for an Icon Appeal

Millers and millwrights of the past left the tools to save UK mill icons and train the next generation. We need your help locating their records, preserving them in our archive and making them accessible to modern craftsmen. By supporting

Funding secured from the Swire Charitable Trust for 2025 and 2026

We are pleased to have secured a grant from the Swire Charitable Trust to support the preservation of millwrighting skills. Our first priority is to establish a national consensus on the current needs of the sector, identify critical knowledge gaps,

The past, present and future of millwrighting

The history of a unique trade The uniqueness of millwrighting is also one of its greatest challenges. Once the preserve of carpenters and timbers, innovations were already taking hold in medieval mills. More intricate gearing and camshafts produced reciprocal motion,