|

| The Miller of Dee, from a Northwestern Miller cover. |

| Following on from the story of Puss in Boots, I thought it would also be interesting to tell the story of the Miller of Dee. Millers were known throughout history as being dishonest. Two of the most well-known stories connecting millers and dishonesty are related in Chaucer’s Canterbury tales; the Miller’s Tale and the Reeve’s Tale. The miller’s tale tells us of dishonesty and the Reeve’s tale describes a miller as a thief. Chaucer refers to the old proverb “Every honest miller has a golden thumb”, meaning honest millers are as rare as men with golden thumbs, or else referring to the miller putting his thumb on the scales to cheat his customers, thus getting more money and becoming richer. But we very seldom hear of ‘an honest miller’, so I thought this story should be told. Some may remember the last lines of the poem as: I care for nobody – no not I If nobody cares for me! This change came about during the middle of the 19th century and it gave an entirely different significance to the original, implying the miller was an unpopular figure in the community who deliberately defied public opinions. Here is the original story. |

| The Miller of Dee |

|

| Charles Mackay |

| The “Miller of Dee” is the title character of a well-known traditional folk song and story, popularised by poet Charles Mackay, about a happy, contented miller living by the River Dee. While working, he sings that he envies nobody, and no one envies him. The King hears him, admits he envies the miller’s contentment, and says the miller’s humble life is more valuable than his own crown, declaring men like him are England’s pride. Hence the moral of the story illustrating that true happiness comes from a simple and content life rather than wealth and fame. The poem was actually set to music by Beethoven (4 English Songs, WoO 157: No. 4, The Miller of Dee). There dwelt a miller, hale and bold, Beside the river Dee; He worked and sang from morn till night – No lark more blithe than he; And this the burden of his song Forever used to be: “I envy nobody – no, not I – And nobody envies me!” “Thou’rt wrong, my friend,” said good King Hal, “As wrong as wrong can be; For could my heart be light as thine, I’d gladly change with thee. And tell me now, what makes thee sing, With voice so loud and free, While I am sad, though I am king, Beside the river Dee?” |

|

| The Miller of Dee, from a Northwestern Miller cover. |

| The miller smiled and doffed his cap, “I earn my bread,” quoth he; “I love my wife, I love my friend, I love my children three; I owe no penny I can not pay, I thank the river Dee, That turns the mill that grinds the corn That feeds my babes and me.” “Good friend,” said Hal, and sighed the while, “Farewell, and happy be; But say no more, if thou’dst be true, That no one envies thee; Thy mealy cap is worth my crown, Thy mill my kingdom’s fee; Such men as thou are England’s boast, O miller of the Dee! |

| The mills on the Dee |

| While the weir at Chester is very familiar, many people perhaps do not realise that its original purpose was to be used to power the Dee Mills which used the River Dee to generate the power to grind corn and carry out other industrial processes. The mills are largely overlooked by historians apart from a few references and an excellent book by local historian Roy Wilding. Today the most obvious relics of the mills are the disused hydro-electric plant opposite the Bridgegate and the restored (but non-operational) water wheel at the head of the salmon steps on the Handbridge side. For almost nine centuries the mills were a significant source of income for those that controlled them and are a major landmark in many old depictions of Chester. The mills were also the source of much dispute concerning the monopoly which the operator of the mill had on grinding corn in Chester. |

|

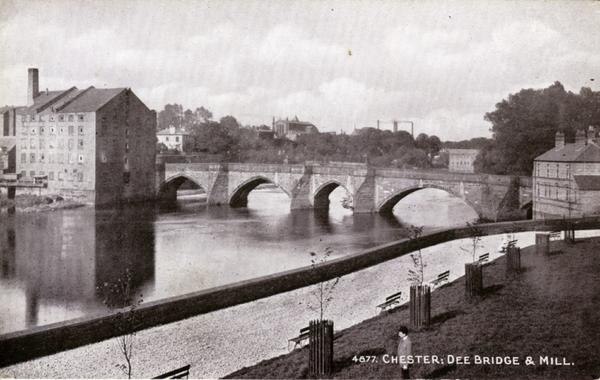

| Dee Bridge and Mill, Chester – WPAC-WAT-00028 |

| The mills along the tidal River Dee in Chester were tide mills, but they were also operated in conjunction with a weir, and the mills had to stop working at high tide when there wasn’t enough downstream flow to turn the waterwheels. Throughout the centuries the weir was used to provide the power for corn, fulling, needle-making, snuff and flint mills, and at times to pump water uphill to the city and generate electricity. The weir is at the normal tidal limit of the River Dee, although spring and neap tides will often flood over it. One consequence of this is that the mills could not be operated continuously but had to stop working at high-water, when there was insufficient downstream flow to operate the waterwheels. For centuries the mills would be worked at times which varied with the tides. |