| This newsletter contains another extract from our online exhibition on Renewable Energy, created by intern Polly Bodgener. You can view the whole exhibition here. |

|

| Kariba Dam, Zimbabwe-Zambia, 1968. Photo Peter Fraenkel. |

| Hydropower can be generated in many different ways. It can come from tides, waves, and rivers, all of which have unique properties that make them suited for generating electricity. Wherever water flows, there is energy. Much like water itself, the history of waterpower has seen many ebbs and flows. Even the word waterpower has subsided in favour of hydropower. Waterpower was used throughout the Industrial Revolution, and global interest in hydroelectricity exploded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, in the UK today, hydropower has seen less implementation than might be expected, especially compared to the growing popularity of wind power. |

| Early Examples of Waterpower |

|

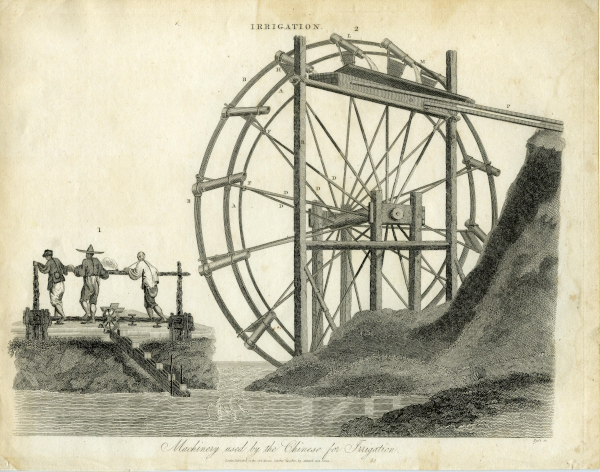

| “Machinery used by the Chinese for Irrigation” – engraving from 1811 – MCFC-ENG-006 |

| Water power has historically been used to perform mechanical tasks, such as pounding grain, breaking ore, and producing pulp for papermaking. Examples of historical water power use can be found across the globe. It is difficult to determine when the first waterwheel was invented, but descriptions by classical writers like Antipater of Thessalonica and Pliny the Elder suggest that water-powered devices have existed since at least 300BCE. The horizontal waterwheel is thought to have been developed in Byzantium and the vertical waterwheel in Alexandria. Other early innovations were conceived in China between 202BC and 9AD. Further information about early water power can be found here. |

| Reinventing Ancient Technologies |

|

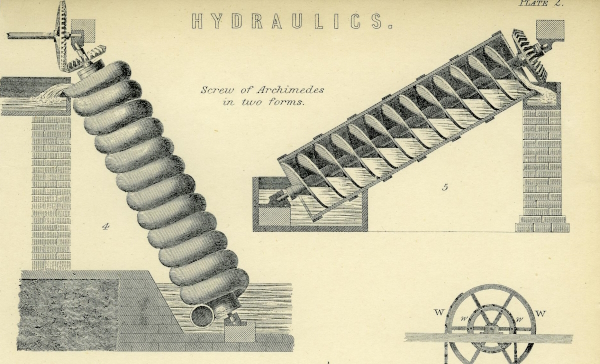

| 19th century engraving of Archimedes Screw – MCFC-ENG-002 |

| Ancient technologies can teach us a lot about diverse potential applications for waterpower. The Greek polymath Archimedes invented the screw in Egypt in 3rd Century BCE for the purpose of raising water. In the 21st century, this ancient technology has been redesigned to generate hydroelectricity. Rather than pumping water up, hydroelectric screw turbines are turned by fast water entering the screw from the top. A generator attached to the base of the screw then converts the rotational energy from the falling water into electricity. |

| Improved Water Turbines |

|

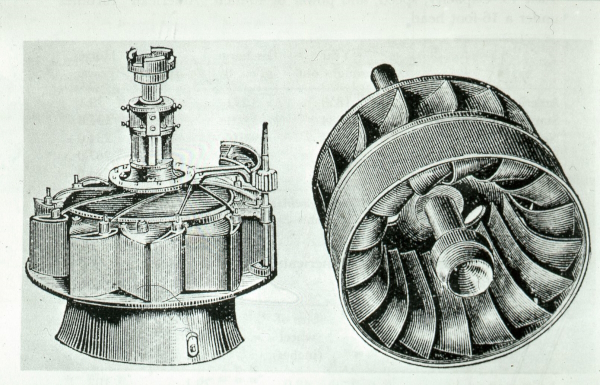

| “New American Turbine 1894, Hunter” – RHSC-09-094 |

| Many turbine designs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries sought to improve on the relative inefficiency of the traditional waterwheel. For example, Lester Allan Pelton’s efforts to redesign overshot waterwheels led to his invention of an impulse water turbine in 1880, and in Austria in 1913, Viktor Kaplan invented a propellor turbine with adjustable blades. A major advance in the generation of hydropower came even earlier. In 1849 in Lowell, Massachusetts, British-American engineer James B. Francis developed a new type of reaction turbine for use in the city’s textile mills. By creating a sideways waterwheel, Francis was able to improve on the efficiency of earlier turbine designs. A reaction turbine uses changing water pressure to directly move the vanes on the runner. As a result, the Francis Turbine operates best when filled entirely with water. Like Archimedes before him, Francis’s turbine was soon adapted to the modern need for electricity generation. To this day, the Francis Turbine remains the most widely used turbine design in the world. Twenty-two are still installed inside the Hoover Dam in Nevada. |

|

| Grand Coulee Dam. Photo by Gregg M. Erickson, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons |

| The world’s first hydroelectric project was realised in 1878, when water was used to turn a Siemens dynamo and light an incandescent lamp at Cragside in Northumberland, England. Hydroelectricity’s potential did not stop here. Projects would only increase in scale and ambition. In 1895, the Edward Dean Adams powerplant was created at Niagara Falls, and was at the time the largest hydroelectric development in the world. Hydroelectric dams are millponds writ large. While the installation of a watermill would result in changes to smaller watercourses and the creation of loch and quay systems, dams flood entire valleys, storing up enormous gravitational energy. Multiple hydroelectric projects were built under President Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, including the Hoover and Grand Coulee dams. By 1940, hydropower accounted for 40% of the USA’s electricity generation. Larger dams were still to come. Brazil opened the Itaipu Dam in 1984, which initially operated with a capacity of 12,600 MW and has since been upgraded to 14,000 MW. |

| You can view the rest of Polly’s exhibition here |