|

| This blog is based on several oral history interviews with our founder Mildred Cookson about her time as the miller at Mapledurham watermill. You can read transcripts of the full interviews on our catalogue. |

| Beginnings |

| I grew up in Blackpool in Lancashire. It was just mum and dad and me; we started off in the south of Blackpool and then moved up further north where it was a bit quieter. And there we were surrounded by around fourteen windmills, and that’s how it all started. I went round looking at all the mills, drawing and painting them. I also learned how to go about making cogs and dress millstones with a gentleman called Walter Heapy, an engineer who was working on the repair of Marsh Mill back in the seventies. |

|

| Lacey Green Windmill, 1971, photo Guy Blythman – GUYB-25503 |

| Then when I moved down south after getting married, I started looking at mills in the local area, and there was one that looked particularly interesting, Lacey Green Windmill at High Wycombe, the oldest smock mill in England. It was completely derelict at the time, it looked as if it was about to fall down, but it was quite an iconic vision. I used to go there every week, painting and drawing it, and one day a gentleman came up and asked me if I liked mills.We got chatting, and he said he was going to repair the mill, and invited me along to a meeting in the village hall. So along I went, and there was this gentleman on the raised platform with a model of the mill with lots of strings round it. ‘This is how I’m going to do it,’ he announced, and he pulled on the strings, and to my amazement it completely untwisted the mill. |

|

| The repair of Lacey Green Windmill, 1970s, photo Peter Jennings – JENN-7792 |

| ‘That’s all very well on a model, but it will never work in real life!’ I thought. But in fact that’s exactly what happened. The gentleman was a millwright called Chris Wallis, he was the son of Sir Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the bouncing bomb for the dam busters. He had entered into a partnership with another millwright, David Nicholls, and they were going round the country repairing mills. |

|

| Chris Wallis (second from right) with volunteers at the restoration of Chinnor post mill, 1993 – CHIN-21665 |

| One day as I was helping with the repair at High Wycombe, Chris said to me, ‘Why don’t you go and look at the mill near you?’‘Yes, but it’s a watermill, not a windmill!’ I said.‘But it’s a nice one, and we just repaired it,’ he replied.So off I went down to Mapledurham to look at the mill. There I met David Nicholls, who was milling there for the estate. But he wanted to get back to millwrighting, he wasn’t planning on ending up as a miller. So over the next few months I went down there every week and he showed me what to do. |

| Learning on the job |

|

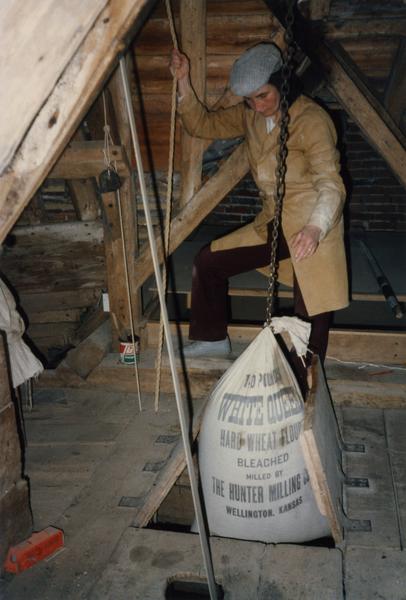

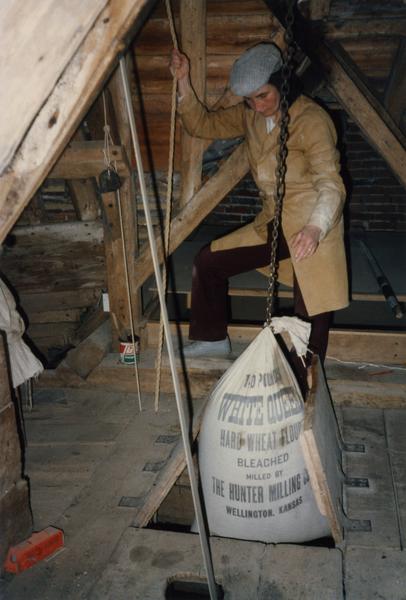

| Mildred at work lifting sacks of grain at Mapledurham Mill, 1986 – MCFC-1122134-04 |

| One Sunday morning at about half past nine we set the mill going. David looked at his watch. ‘Right, I’ll come back at five o’clock and see how you’ve got on,’ he said. So it was rather an interesting initiation – but fortunately nothing went wrong!And that’s how I got into milling. It was a case of just learning on the job. I was there for about four or five months with David Nicholls and I learnt quite a lot from him, but there’s always so much that you can’t teach until it happens. About a month or five weeks in, I was busy milling when all of a sudden there was a sound like a gunshot going off – it frightened the living daylights out of me! It was a tooth that had cracked on one of the main gear wheels.David had warned me about this – if it happens, he said, you must stop the mill as fast as you can, because once one tooth has gone, it will strip the whole lot off. The gear that’s meshing with the teeth will hit the next tooth twice as hard and crack that one, and then the next, and the whole lot will go. But you have to stop the mill in the right order – you can’t just go and shut the waterwheel down, you’ve got to disengage the stones first. |

|

| Checking on the flour chute – MCFC-1122134-09 |

| So it was a case of learning as you went along, not by mistakes so much as by intuition. Living with the mill is the most important thing – you’ve got to learn it and understand it, and it speaks to you. You get to know the sounds of the mill. I could always tell if a paddle was coming loose on the waterwheel, it made a slightly different noise slipping in and out. Sometimes you can start the mill going in the morning and just know it’s not right, so I would shut down and have a look round, and find something out of place – ‘Ah! That’s the problem!’ Then once I had sorted it out, I would start the mill again and it was absolutely fine. |

| Flooding |

|

| Flooding at the mill, 2007 |

| Every winter the mill would flood at least two or three times. There’s nothing you can do about it – you can’t stop the River Thames. The environment agency would give me a quick ring and say, ‘Heavy rain up north at Oxford, it’ll be coming down in three to four days. We’ve opened some sluices up, but you’re going to get high water.’ So I would mill two or three days on the run to make sure I had got a good stock in, because you were never sure whether it was going to flood for a week, or a month, or even longer.And then once the river starts coming up it comes up very fast indeed. You can actually watch it rising, it’s quite frightening. The main thing to do then is to chock the waterwheel – putting wooden planks at the front and the back so it can’t move. Otherwise once it gets flooded it will start going backwards, and that’s not good for the wheel. The pit wheel inside the mill would be chocked as well. |

|

| Chocking the waterwheel |

| Quite a few times the river rose so high that it actually came into the mill, which was quite scary. The worst time it was up to my knees inside the mill. You can’t do anything about it, you have to wait till everything goes down, and then you have thick mud on the floor, with dead fish, and a really horrible smell. It can take three or four weeks to clear out all the mud, and two months to actually dry out. Then you get a mark all round the wall where the flooding was, and even if you paint over it, it still seems to come through. |

| Life at the mill |

| I had a team of young men helping me at the mill over the years. They came from local schools or colleges and just wanted a bit of experience, and they were all brilliant. I used to say to them when they started, “Look, if you’re not enjoying it, tell me, because I don’t want to waste my time teaching you stuff if you’re not going to carry on.” And not one of them left. I think they enjoyed doing something different, hands-on. I suppose computers and technology weren’t around as much, and they loved seeing the machinery, the big gears like the inside of a clock. |

|

| You build up quite a friendship with local farmers as well. Sometimes I would mill for a local farmer and he’d give me half a pig or half a lamb in payment, like they did in the old days. The estate changed over the years – there was a shepherd when I first went there, and I used to go down and watch the sheep shearing, and there were harvest festivals and bonfire nights, everything was really based around the local community. But people moved on and people retired, and towards the end of my time there it had all disappeared, which was a shame. Times change, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse, but you can’t stop things from changing, I’m afraid. |

|

| Wildlife at the mill – a heron and a robin |

| But it was such a privilege to be able to work a 400 year old mill, and enjoy the surroundings – the river with the kingfishers and grebes, and swans nesting right next to you; the fishermen you could talk to, who would ask me to photograph them with their proud catch. You couldn’t relax, in one sense, but on the other hand it was very relaxing – just having the water all round you, and thinking of how the water that had gone under my wheel was now flowing through London, past the Thames Barrier and out into the Channel. It’s a beautiful building with such a history behind it, and it’s very special to have been part of that history. |