Since November 2023, I have been working as the Renewable Energy Intern at the Mills Archive Trust. My main project has been to create a digital exhibition exploring the often overlooked connections between traditional milling and renewable wind and waterpower technologies.

Amidst the twists and turns of my initial investigations, something vital caught my attention:

The Question of Language

I came into this project not as a molinologist or a historian. It is a shame but not a surprise that I, like so many others, had little more than a passing knowledge of mills. What I did know was acquired mainly through walks in the countryside and landscape paintings, and from playing in the ruins of a local gunpowder mill as a child. Lacking the technical know-how, I instead I approached the initial investigations as a recent literature graduate steeped in ecocritical theory might. I began with language.

A large part of my role is dedicated to figuring out ways to communicate the relationship between traditional mills and contemporary renewable energy initiatives. With over three million records to scour, the Archive is full of fun words, technical jargon, and brilliant provincialisms that I gleaned along my journey. ‘Molinology’ was a new one to me!

I have begun to create climate change glossaries for different reading levels. Understanding mills – how they work, how they shaped the land around them – can provide historical context for the green transition. By bringing the rich vocabulary of milling into the context of the climate crisis, molinology can play a part in the fight to protect our planet.

Any suggestions for words or definitions are welcome!

The differences between how people describe traditional mills and how people describe turbines have been particularly generative. Renewable energy initiatives have been haunted by general ambivalence. Much of this confusion and uncertainty comes down to how renewable energy projects are described. Tackling the common complaint that windfarms are noisy bird-killing eyesores was a captivating place to start. What emerged was a fascinating comparison of the rhetorical tactics used by today’s fossil fuel lobbyists and the early enthusiasts and sceptics of wind-power.

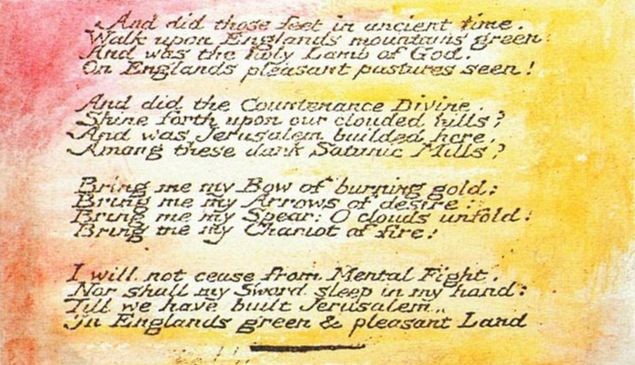

‘And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?’

A Vernacular for Turbines

I’ll spare the reader a lengthy analysis of William Blake’s poetry, but I was staggered by the ubiquitous misappropriation of his oeuvre. Fossil fuel lobbyists and opponents of windfarms have used the phrases ‘green and pleasant land’ and ‘dark satanic mills’ for their own ends. These well-worn excerpts come from the preface to Blake’s Milton (1810), and have been abstracted from his idiosyncratic and often complicated worldview. Blake’s poetry wrestles with how unchecked industrialisation left people alienated from nature, from others, and from themselves. At the same time, the pastoralism of the ‘green and pleasant land’ was being leveraged by writers on both sides of the energy debate.

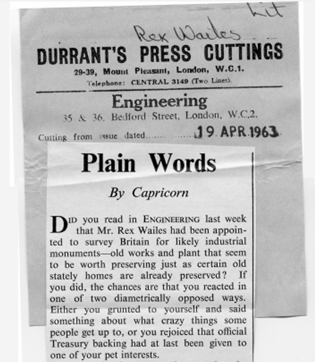

It became apparent that the language of mills and renewable energy was far more complex than I had anticipated. Unlike the turbine, traditional mills tends to be romanticised in word and image: ‘picturesque’, ‘pleasant’, ‘vanished age’ were all words I came across. The following selection of press cuttings barely scratches the surface of how often the ‘picturesque’ appears in the archive’s online catalogue:

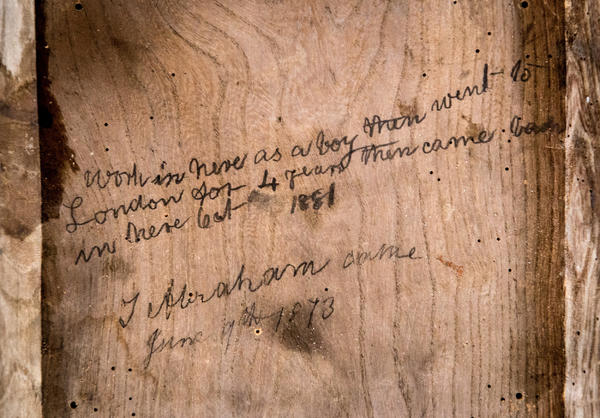

Traditional mills were shaped by local labourers and millwrights, and over time became full of their language, in some cases quite literally through graffiti and engravings. Turbines, on the other hand, are still relatively new, and lack that same vernacular richness. They are seen less as part of the ‘whole’ as a mill might, but as something ‘alien or inappropriate’ to the landscape.

It is not my intention to rehabilitate the perception of wind turbines or tidal stations. I want to show how archival aterials record not only the persistence of concerns about renewables, but a visual, technological, and linguistic history that has celebrated innovation since before the first turbines were erected.

Our language for describing mills and turbines is still evolving, still dynamic. After all, heritage and renewable energy initiatives have an obvious shared motive – the conservation of this planet’s wonders.

Reflections on Interning at the Archive

The staff at the Mills Archive Trust have opened my eyes to the skill and effort it takes to run an archive day-to-day. The above explorations have formed just a small part of my larger explorations in the digital exhibition. The notion of the ‘picturesque’ and how land is described and used is investigated in a section titled ‘The Mills Have Eyes’.

I am very excited to learn more about the history of renewable energy in the coming weeks. In particular, I am looking forward to expanding on the interlocking ideas about climate anxiety, perception, and wind and waterpower.

Polly is an intern working on the Reading EmPOWERed project, a two-year endeavour funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

This initiative focuses on the study of renewable energy, with a particular emphasis on generating electricity from wind and water power. It explores the transition from traditional mills to modern structures and examines the role of wind and water turbines in combating climate change. Polly’s work and subsequent reflections would not have been possible without the Fund and National Lottery Players.