Nathanael Hodge

| Happy New Year to all readers of our newsletter! 2023 is the Mills Archive’s 21st birthday, and in honour of this we will be featuring a series of 21 gems from our collections in these newsletters in the coming months. Our first gem is a beehive quern dating back to the Iron Age, from the Mildred Cookson collection. | |

| It’s the oldest item in our collections – a heavy, smooth, conical lump of rock, about nine inches across and four and a half inches high. Although this ancient artefact is probably over 2000 years old, in its day it was a revolutionary new form of technology, both literally and metaphorically. Today we are familiar with each new year bringing new technological advances. Last year it was AI driven text and image generation, and who knows what this year will bring. We can hardly imagine what it was like to live in a time when most of the tools people used as part of their everyday lives were the ones they had inherited from their parents and grandparents before them, when life had been lived in largely the same way for centuries, and when a new form of technology would have seemed wholly unprecedented. For thousands of years, from perhaps as early as 4000 BC or before, the form of millstone used in Britain and the world over was the saddle quern. It’s the type of millstone shown in the Egyptian tomb models below, from a model bakery found in the tomb of the royal chief steward Meketre, dating to c 1980 BC, and it consists of a large flat stone with a smaller upper stone which would be rubbed back and forth across it. | |

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544258

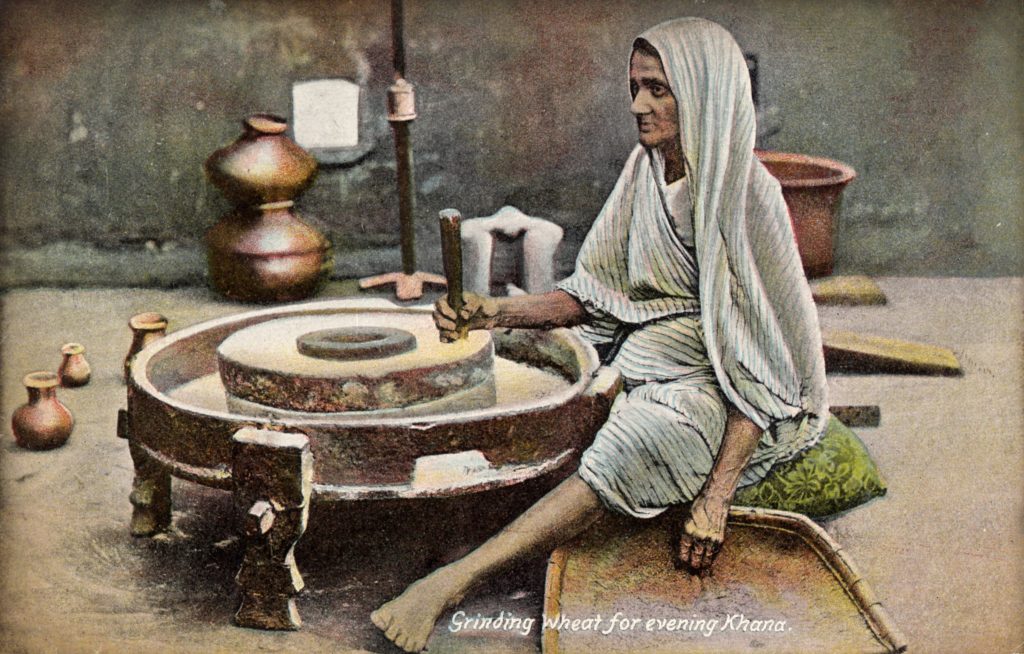

| Grinding enough flour for the daily bread at a saddle quern was very strenuous work. Ancient texts indicate that it was a task usually given to women. Research from the University of Cambridge in 2017 indicates that Neolithic women had stronger arms than today’s elite rowers due to spending up to five hours a day grinding wheat. Slaves and prisoners were also given the task of milling – the Exodus story in the Bible, for example, refers to the “slave girl who is behind the handmill”, and in Isaiah’s prophecy of the destruction of Babylon, the city is pictured as a queen forced to do the work of a slave: Come down and sit in the dust, O virgin daughter of Babylon; sit on the ground without a throne, O daughter of the Chaldeans! For you shall no more be called tender and delicate. Take the millstones and grind flour, put off your veil, strip off your robe, uncover your legs, pass through the rivers. Although milling was a task given to those considered of lower status, the millstones themselves were highly valued. A biblical law states No one shall take a mill or an upper millstone in pledge, for that would be taking a life in pledge – in other words, millstones should not be taken as security against the repayment of a loan, because to take someone’s millstones would deprive them of their means of survival. In the Iron Age, for the first time in thousands of years a completely new type of mill appeared – the rotary quern. It was significantly more efficient, taking perhaps only hour to grind the wheat for the day’s bread, and made de-husking the grain much easier. It also must have seemed almost magical due to the way in which the grinding of the wheat is hidden – in using a saddle quern it is easy to see how the upper stone crushes the wheat; in a rotary quern, wheat is poured in, and as if by magic, flour comes out. | |

(Mills Archive Collection, MCFC-10529)

| The new type of mill was only made possible by the introduction of iron, enabling the creation of both the iron tools used to shape the stone and the iron spindle around which the upper stone rotates. Grain was fed into the ‘eye’ in the centre of the upper stone, which was turned using a wooden handle inserted into a hole at the side. Grain is crushed between the rotating upper stone and the stationary lower one, exiting as meal all around the rim. | |

| The exact time and place of the rotary quern’s origin is not certain, however they seem to have arrived in Britain in around 400-300 BC. A variety of different shapes and sizes were in use. This one is known as a beehive quern due its similarity in shape to a traditional dome shaped wicker beehive. It was found in north west Essex in the Stansted area. It is made of Hertfordshire puddingstone, a conglomerate sedimentary rock formed of flint pebbles deposited in clay which was then hardened into stone. Sadly, the lower stone is missing. We can only guess at the effects the new type of mill had on society, but in providing a means to produce flour much more quickly and in greater amounts, it must have led to significant social changes, comparable to the effects of the introduction of the even more efficient water powered mills in the Roman period, and the development of modern roller milling technology in the 1800s. |

Beehive querns continued to be used into the Roman period, gradually being replaced by larger and thinner stones. Even with wind and water powered mills, handmills still continued in use into the Middle Ages, although efforts were sometimes made to prevent their use so as to force the tenants to have their grain ground at the local mill, paying a toll to the lord of the manor.

Quernstones continued in use for grinding oats in the Scottish isles into the 20th century.

Quern in use in Shetland, 1940s. Photo by E M Gardner

(Mills Archive Collection,

EMGC-04-16-07)

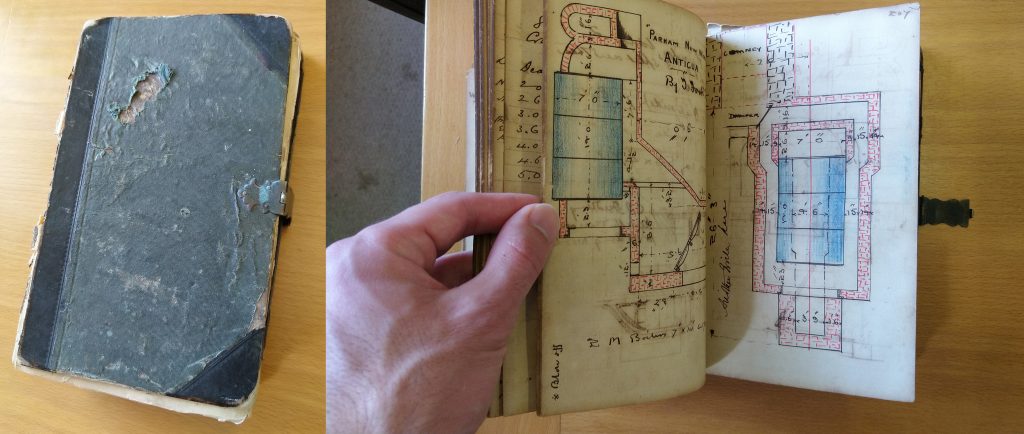

New collections

| As we do every year, we have compiled a list of all our acquisitions in the last year to submit to the National Archives. In 2022 we accessioned a record 303 new boxes of material. Two thirds of these were from the collection of the late Alan Stoyel, which we will be busy working on for a long time to come. Other significant additions to the archive included: · Millwrighting drawings and other records relating to work on wind and watermills from millwrights Owlsworth IJP · The records of the Mills Research Group which wound up its activities last year · 50 more boxes of casework from the SPAB Mills Section · Mill photograph collections from John Martin Gregory, John Bicknell, E W Henbery and Anthony Edward Beare · Collections from the Great Chishill Windmill Trust and Wilton Windmill Society · The notebook shown below from sugar mill engineer E Y Connell (d 1936) relating to his work on the steam powered sugar mills of the Caribbean |