A few weeks ago we featured the history of the firm Holman Brothers of Canterbury in our newsletter. In this newsletter we will look in more detail at the employees of the firm, including their experiences in the First and Second World Wars.

The Staff of Holmans

HOLM-04-HB058)

| It would be impossible to calculate how many employees walked through the gates of 12 Dover Street, Canterbury over the 159 years that the Holman millwrighting firm was in operation, but from the records we hold it seems likely that there were more than 300. Those employed included millwrights and wheelwrights, carpenters, blacksmiths, turners, engineers, engine drivers, painters, and bricklayers. One of the earliest and longest serving employees recorded was Ethelbert Thomas Kemp who, on the 1841 Census, was an apprentice wheelwright and by 1861 had moved to one of the Holman cottages at 13 Dover Street where he stayed until his death in 1890. It’s estimated that around 20 properties were purchased, leased and sold on Dover Street, Old Dover Road and other surrounding roads for the purposes of accommodating employees. The cottages were not entirely separate, but were interlinked – one bedroom might be over another’s sitting room and so on. The cottages had dirt floors but were equipped with running water, flushing toilets and gas. The Holmans were remembered as good landlords. | |

| Workplace traditions were a mainstay at Dover Street. One included the staff addressing Harry Branford Holman’s sons as Mr. Frank and Mr. Tom. Presumably this was to ease confusion between the five Holman men at that time. Another, which was recognised throughout Canterbury, was the Holman bell which hung outside the carpentry shop at Holmans from 1854 until the 1942 bombing raid, described below. It was rung at seven o’clock in the morning for the men to start work. It rang again at 8.30 and 9.00 for the breakfast break, again at 1.00 and 2.00 for the dinner break. The men worked a 48-hour week finishing at one o’clock on Saturdays and five o’clock during the week. The only holidays the employees were entitled to, according to 1891 records, were the six bank holidays. Mrs. Wood remembers that the gates were closed at 5pm precisely every night ‘people would set their clocks by it’. At one time Canterbury was supposed to have taken its time from Holman’s bell and Williamson’s Tannery hooter. |

Accidents and deaths in the workplace

| As with many industrial businesses, unfortunate accidents and deaths sometimes happened. Some of those that occurred to Holmans’ employees were reported in the local newspapers of the time. Here are some examples. On the 15th of January 1856, the Kentish Gazette reported that: On Wednesday, William Marsh, a young man in the employ of Messrs Holman, wheelwrights, in Dover-lane, while fixing a heavy shaft in the lathe for turning, sustained a compound fracture of the leg by the tackle breaking and the shaft falling on his limb. The 1851 Census reveals the above to be William [Henry] Marsh living at 26 Cross Street, Canterbury, aged 14, and working as a millwright. He survived the accident and by 1871 has changed profession to a pattern maker and was living in London with his wife and family. He died in 1883. |

HOLM-04-HB072)

| On the 7th July 1868 the Gazette included the following story: Yesterday evening, a very serious accident happened to a man named William Knott, in the employment of Messrs. Holman, iron-founders. It appears that along with other workmen, he was engaged in raising a girder, weighing about two tons, in the Star Brewery, when it suddenly swerved to one side and fell upon him, near the region of the heart. The ribs were driven in upon the heart, and Knott sustained other injuries of a serious nature. Mr. George Beer had the poor man immediately sent to the Kent and Canterbury Hospital, where he remains, but Mr. Hutchings entertains no hopes of his recovery. Sadly, William Knott died soon after. The Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald of 25th July 1891 reported: A young man named John Fry, a smith, in the employ of Mr. T. R. Holman, of Dover-street, met with an extremely painful accident on Saturday. Shortly before 9 a.m., the employés were moving a quantity of machinery when a heavy piece fell upon Fry’s right foot and burst it. He was quickly released and removed to the Kent and Canterbury Hospital in a fly from the neighbouring stables of Mrs. Fagg. |

Crime

| Criminal activities by employees happened on occasions, and the two descriptions that follow give an insight into some misdemeanours. On the 27th October 1857, the Kentish Gazette reported on a case in which two employees were charged with embezzling and obtaining money under false pretences from the firm. The two men were Frederick Head and Robert Best, and had been working for Holmans at Chitty’s Mill, Deal. John James Holman claimed that they had drawn money from the firm’s account without permission and without informing him. The magistrates dismissed the case, considering the evidence insufficient to prove the charge. |

GJON-IMG-04)

| In July 1882, Herbert George Sladden, an apprentice millwright to Holman and Collard, was charged on remand, along with Walter Uden of Dover Street, ‘with a robbery of tools at Nackington […] on the 24th April.’ A Police Constable ‘went to Messrs. Holman and Collard’s works in Dover Street and searched a tool chest there used by Sladden, in which he found the two bradawls, bevel, bit, and gauge produced.’ He and Uden were taken to court at the East Kent Quarter Sessions on 17 October 1882 where both were found not guilty of larceny, with Sladden having turned Queen’s evidence against the other perpetrators. This was not the first time Sladden had been arrested for criminal activities. Newspaper reports back to March 1882 show that he had been remanded, and later acquitted, of several thefts of various items around the city. What’s interesting is that both Sladden and Uden vanish from all UK records following the trial. Further research revealed that Uden had emigrated to America in 1885 and ended up in Chicago. |

War and the Holmans

| Holmans, like many businesses, was affected by the wars. Employees served in the Second Anglo-Boer War, World War 1, and World War 2, with the premises being damaged during the latter. Some of those who served didn’t return, some returned to work at Holmans, and some continued in military service. |

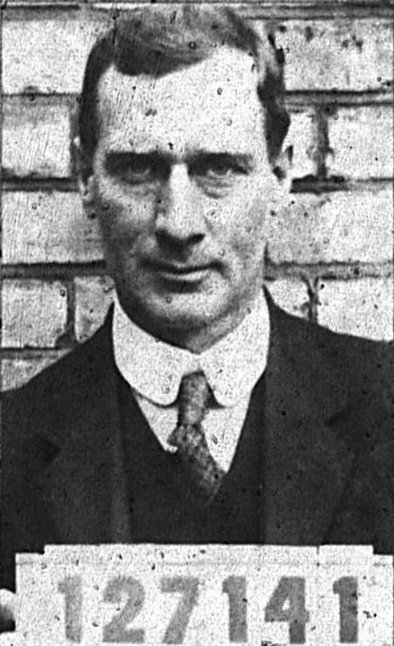

The earliest record of a member of the Holman staff volunteering for active service was in 1900. Frank Richard Harvey of Chartham began working at Holmans in December 1896 at the age of 15. On 9 January 1900 Holmans sent a letter to the Officer Commanding the East Kent Volunteer Reserve giving permission to his release from his apprenticeship with them so that he could join the forces in South Africa.

Further research shows that Frank was a volunteer with East Kent 1st Volunteer Battalion the Buffs and received a medal at a Canterbury presentation of war medals on 12 October 1901. He returned to serve out his apprenticeship, but later joined the Merchant Navy from 1919 with the rank of 1st class engineer. From 1927 he was engineer on the Highland Monarch, a passenger ship requisitioned in 1939 as a troop and supplies ship running the Winston’s Specials convoys to Freetown and Durban in Africa. Frank was discharged in 1941 at the age of 60.

Frank Richard Harvey. Crown Copyright, image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives, London, England.

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

| Holmans, like many businesses, suffered when men were called up for the First World War. Those who faced active service had to go. However, Holmans negotiated with the War Office by offering the company for munitions work as a means to retain those who were called up for munitions work and to keep the company going. A letter of February 1916 to the Ministry of Munitions stated: The majority of the workmen we have left in our workshops are being pressed to sign on for munitions work. We enclose list of men in our employ at the outbreak of war & have underlined those who have already left for service with the government & those who are now asked to go on munition work. You will see that if these are taken it is absolutely impossible for us to keep on. We give a short description of the class of work we do & with which at the present time we are simply inundated. If you say that this work is to be put on one side, we will do it & devote our energies to such work as you can send us but if our men are to keep on with their present work please let us have some assurance that we can give them that they are doing their duty. … This is an old established millwrights, agricultural & general engineering repair shop. We make little or no new work our men’s time being wholly devoted to attending to breakdowns & keeping in repair (for customers) agricultural machinery, flour mills, powder mills, water works & co & in addition these men have to keep in repair our own steam cultivating machinery (2 sets which cultivate on an average 2000 acres per year & 4 sets of thrashing machinery). The letter included a list of staff indicating who had already left for military service and who was now being pressed for munition work. The firm faced a similar problem of staff shortages during the Second World War. During this time, they were also at risk from air raids. During a big air raid in June 1942, the Holman Cottages in Dover Street were set on fire by sparks from the blazing workshops which had been destroyed by incendiaries. The bell depicted above was half destroyed. However, the fire wardens, among them Frank Holman, got onto the roof and doused the flames before they took a real hold. During the war Tom Holman could sometimes be found on top of the Westgate Towers manning a machine gun post. If a German invasion was reported, he had orders to blow up St Dunstan’s Street to halt their progress. He had been told that the road had been mined and he was shown a control box from where they could be detonated. Later he said that he had doubts as to whether the mines were ‘live’; the rumours being circulated to maintain morale. At other times he was an ARP warden on fire watch duties, along with Frank Holman and other members of staff. A room at 13 Dover Street was turned into a firewatching station where the two men whose turn it was to be on duty, could make tea or even snatch some sleep if there was no raid on. Tom also claimed to be one of the only people who had driven a car down the nave of Canterbury Cathedral, whilst delivering materials when the firm was carrying out bomb protection work. |

Memories and reminiscences

| Documents and records provide one side of the Holman story, but the memories of those who worked at the firm provide an invaluable glimpse into what life was like. A former employee Chris Richardson told Geoff Holman about his memories of life in the firm: Holmans didn’t pay that well. Mr. Tom caused a riot one year. The day before Xmas he told men he had been so busy that he didn’t have time to go to the bank for the wages and they would have to wait until after the holiday. The men went spare, but Mr. Tom managed to get the money and gave them all cigarettes and chocolates to pacify them. Overall Mr. Tom ran the show. Mr. Frank was called ‘Dreamy Daniel’ as he used to wander around in a bit of a dream, but he stayed mainly in the office. There was a discernible atmosphere in the firm, there appeared to be a lot of friction in the office. After I had been there a couple of years I used to be given jobs. Mr. Jack would give me a job, and I would be getting tools together and finding a van when Mr. Tom would come along and say ‘What are you doing, because I want you to go to so and so.’ I would say Mr. Jack had given me the job to go to, Mr. Tom would say ‘Well I want you to go to so and so instead, I’ll sort it out with Mr. Jack.’ The problem was having three bosses, but men were told that what Mr. Tom said went. If you had worked for Holmans and were called up into the Army, you were guaranteed a place in the REME [Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers] as Mr. Jack would put in the word for you. |

| After Mr. Jack left, the impression was that firm was going downhill. The opportunity to act as agents for large firms such as Ford and International was turned down, which was a shame as Holmans were the biggest engineering works in Canterbury. The agencies went to competitors. A high standard was maintained. I didn’t matter how long a job took, it could not leave the premises until it was perfect. One job I had was making large screwed bolts on the lathe. I didn’t polish the ends as they were to be buried in concrete – that was not the point, people would see them before they went in, so I was made to polish them off properly. Mr. Tom had a spare engine for his old Austin York saloon; he made up all the bearings for it. He later got a newer Austin and the old one was left in the yard, but if all the vans were out, we would sometimes have to go out in the old Austin. He sometimes said, ‘You in a hurry to get home?’ I said ‘Not particularly’ so he used to park up somewhere with a view, light up his pipe and sit there for an hour in silence. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do, but as I was getting paid, I just sat there with him deep in thought… He did that several times. |

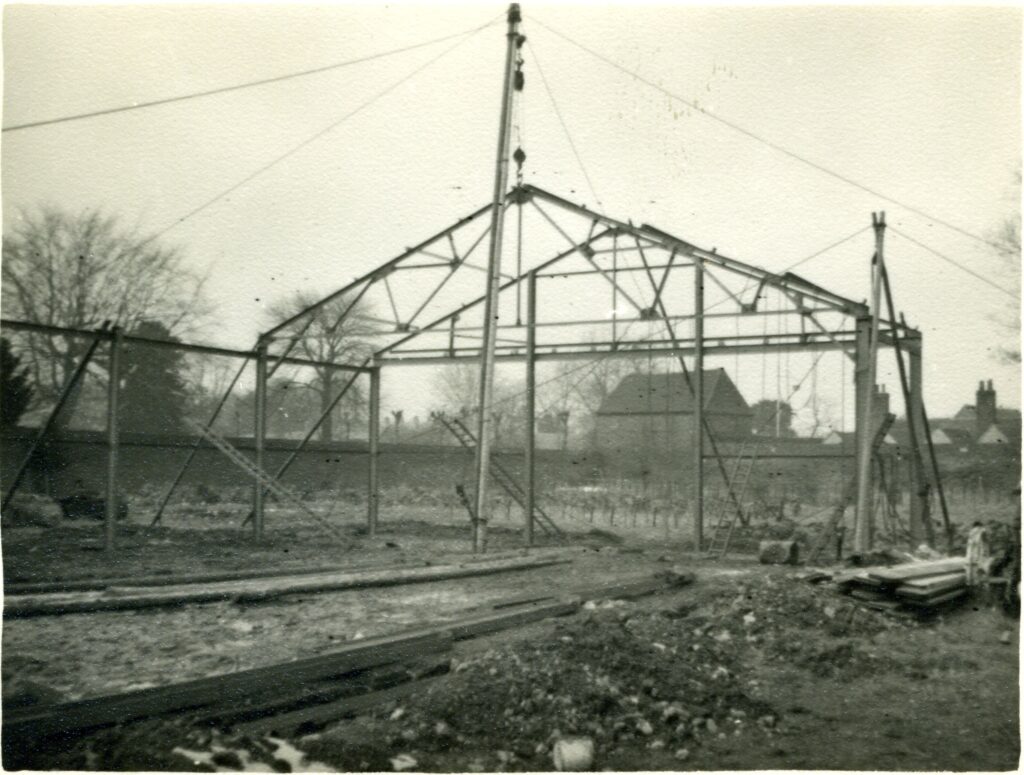

| The staff I remember being at Holmans when I was there were 8 outside crew, Dick Castle was one of 2 blacksmiths, Bert Cook and me in machine shop, 4 mending tractors, engines etc., 1 apprentice, 2 on mowers, 3 millwrights, Jack in the office who used to play organ in the Regal cinema. Steve was the bookkeeper. A new workshop was built in the meadow at Dover Street in the mid-50s to replace the one blitzed in the war. Machinery was gradually moved over from the Old Dover Road. Heating was by 2 coke stoves, which got very hot and were good for making toast. The firm had stands every year at the Kent County show and at 2 ploughing matches. I finished in 1962 and went to Grain Harvesters for more wages. If you would like to find out more you can read the full account of the history of Holman Brothers and the mills they built on our website: https://new.millsarchive.org/2015/03/10/holman-bros-millwrights-of-canterbury-a-history/. |