| A few weeks ago, we featured some of the writing of John Munnings (1916-1987) with his memories about growing up at Mendham Mill, Suffolk, where his father was the miller. This newsletter gives Munnings’ account of his grandfather, also called John Munnings and miller at Mendham Mill. |

John Munnings (1839-1914)

| Unfortunately, my grandfather died a couple of years before I was born, but from tales passed down to me from those who knew him well, he could be cast as a typical miller of his day. He was born at Little Horksley, just on the Essex side of the River Stour, on 25th May 1839. Soon after this his father moved back to Stoke-by-Nayland, where the family had lived for nearly 200 years. My grandfather at the age of 14 started as a miller’s apprentice at Shonk’s Mill, Ongar, in south Essex. I never knew anything about that mill, the only story I ever heard of there being that one night after heavy rain grandfather got up to raise the sluice gate, a type which was raised by chains wound round on a wooden barrel. A short pole was inserted in holes around the barrel for operating. Being in a hurry he went out in his nightshirt, and was heaving on the pole which broke and he pitched headfirst into the raging torrent. |

MUNN-02-01-34)

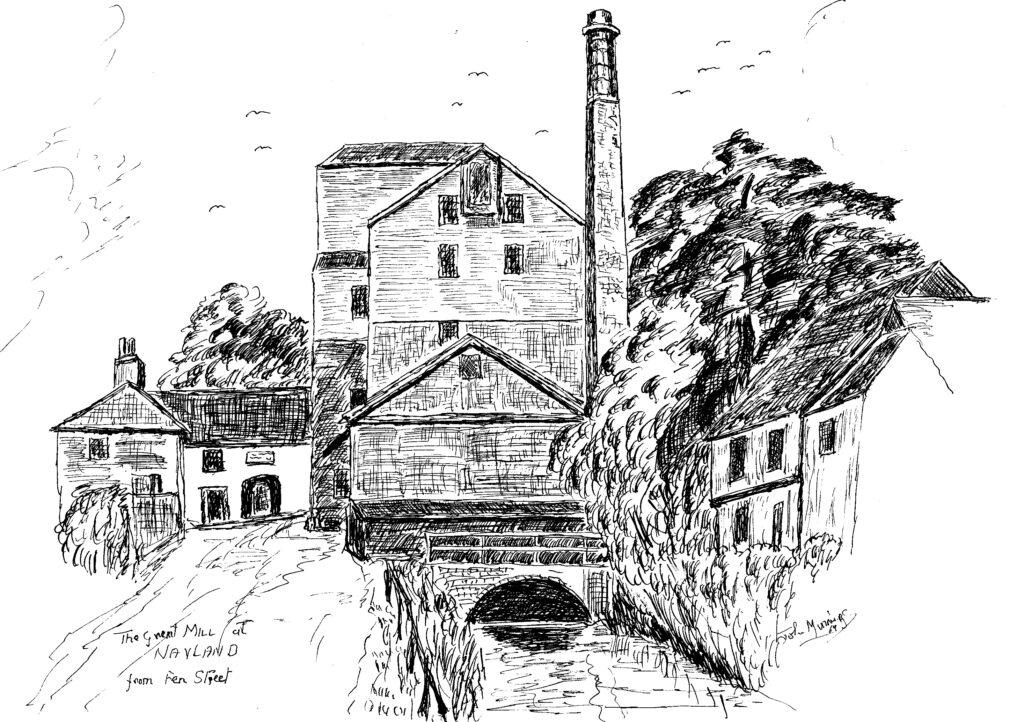

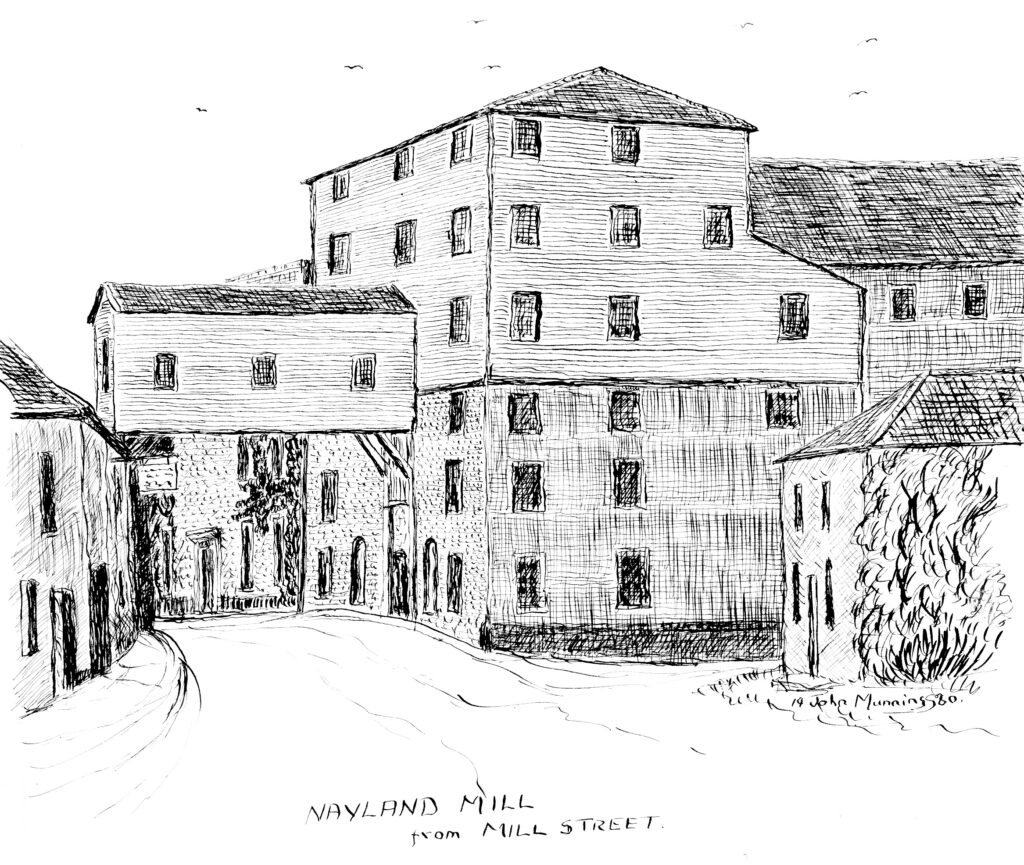

| Two years later in 1855, he went to Nayland mill, which together with Wissington Mill was run by his cousin Jeremiah Stannard, where he remained until 1872. Nayland Mill, very little of which now remains, was then one of the largest water mills in Suffolk. It also had two large steam engines and until 1867 contained 16 pairs of millstones. Stannard was a very ingenious miller in his day. He always had quite a number of apprentices, several of whom later became well known millers in the country, one of these being Mr. George Walker, who was previously apprenticed with a flour miller by the name of Bowman, at Water Newton on the river Nene. After being with Stannard for a few years he entered into partnership with William Cubitt in 1869 at Ebridge Mills on the North Walsham-Dilham canal. He was one of the best known figures at the Norwich corn exchange from 1869 until his death at the age of 93 in 1934. |

MUNN-02-02-020)

| One story I often heard related about Nayland Mill concerned an occasion when the mill was running light (a term used when the mill was getting short of wheat). Three barges with about 400 sacks of wheat on board had been delayed coming up from Mistly Quay, owing to floods, but they arrived on a Saturday morning. Normally no miller would ever take wheat in on a Saturday, but this being a special case the apprentices were given the job of unloading the barges. It was always a difficult job at this mill at Nayland as the mill lucam was extended completely across the road for this purpose. Stannard being very methodical gave instructions as to where the wheat had to be stacked. However, the lads wanting to get away as it was a Saturday, and thinking Stannard has gone to Colchester market as usual on that day, unloaded in record time and literally “hulled the wheat into the mill”. Anyhow, they had just about finished when Stannard came on the scene, and made them all re-stack it, but they learnt their lesson. I often wish I knew more about Stannard and Nayland Mill, but in my younger days one was almost afraid to ask questions of our elders. Often when I have stood by the churchyard wall at Stoke-by-Nayland, and gazed at the magnificent view across Tendering Park, and to Horksley and Nayland, one can almost hear the hooves of my grandfather’s horse trotting past down the road, a journey he did for nearly 17 years. When he moved to Mendham he entered into partnership with George Chase, who had Mendham and Weybread watermills, a windmill known as Weybread Highmill, as well as brickworks and several farms. The partnership lasted until 1887 when Chase was killed, being thrown out of his cart on leaving Harleston Market. This being the middle of the depression of the 1880s, my grandfather was lucky to be able to salvage Mendham Mill out of the wreckage. My grandfather was a jovial, outspoken man, and as a business man and miller he was deeply respected. He would denounce fiercely anything he disapproved of, but he had a genial and kindly disposition, and a hospitable temperament. His characteristic greeting of “How are you old friend” was proceeded by a vigorous grip on the shoulder. These characteristics passed down onto his two sons, Alfred and Charles. Alfred’s outspokenness on questions of right and wrong is well known to the world; unfortunately, Charles died in S. Africa in 1918 aged 34. The others, William and my father, seemed to take more after my mother. It seems almost incredible to-day when I think of the miles grandfather drove in his high-wheeled sulky, but like most millers he always used fast horses, much to my grandmother’s sorrow. She told me how on occasions at night his horse would come galloping down the lane with just the shafts, after which a search party had to go out to rescue the rest of the sulky and grandfather out of the ditch, and how some Saturday nights after attending Framlingham market he would call on old friends at Brundish Lodge and play cards for most of the night. He used to travel the dark roads at all hours of the night, coming home from distant markets with a great amount of money he used to carry in his leather bag, as most bakers and shopkeepers paid in sovereigns in those days. He always carried a large six-chambered revolver, like the guard on the stagecoach. Once I was told of a night in a lonely dark lane when two men tried to stop him, one seizing the bridle, and how he fired the revolver into the air, when the frightened horse leapt forward, knocking the men down. But one day, some years later, the revolver met its end. Apparently in later years it used to lay on the office mantelpiece, and Uncle Charles, a character that no ordinary girl could cope with, had apparently had some sort of row with his current girl. Coming home in the state of going to the devil, he swore he would shoot himself. Grandmother hearing this ran into the office and threw the weapon into the tail hole at the back of the mill, the water here being about 12 feet deep. It is probably still there. Grandfather was a great churchman. He would read morning prayer to the family each morning. At times, in the middle of these, a wagon would arrive laden with wheat. Leaving the family kneeling, he would go to the office for a sample of this particular wheat bought at a local market, climb on to the wagon and check every sack. Everything in order, he would say to the carter, “Alright cocky, you can drive on,” before returning to the prayers. | |

(Mills Archive Collection, DOLM-1123589)

| He always kept two large bottles in his office, one labelled “Gin,” the other “Water”. One hears how when he was out, the boys used to change over the contents. Once a local farmer, coming into the office to give an order and pay his bill, was offered a drink, which he accepted. The boys, saying it might be strong, suggested they topped it up with water, or rather with the water bottle which contained gin. Lucky for them, grandmother had a friend, a nurse, staying with her, otherwise it could have been fatal. But what else could one expect of boys of that calibre who were never short of amusement at somebody’s expense. When Alfred was beginning to get a name for himself in the early 1900s, grandfather came home from market one day only to find him at the back of the mill with a massive canvas, half a dozen ponies in the river and half the men out of the mill chasing them through the river, to get the right effect for his painting. If only one could do that to-day. Unfortunately, any pranks I got up to usually ended in trouble. One which comes to mind happened when I was eight. Being a Wednesday afternoon, we thought Father had gone to Harleston Market, so cousin Robert and I fitted a sail to a rowing boat at the back of the mill, hoping not to be seen, the sail being one of fathers nightshirts. We fitted a cross bar on the mast, on which we put the sleeves. We started off well, with a following wind, but lost control and charged the bank, only to be greeted by Father with a stick. Fortunately for me Robert was four years older and so got the biggest hiding. Long before the war I was out for a walk with Uncle Alfred, on a favourite route along the disused towpath by the river Stour from Dedham through Stratford St. Mary and onto Langham and Boxtead, generally stopping to have a swim in the river on our way in our birthday suits. Often, he would burst out with tales of old; I wish I could remember them all. One that comes to mind was about how, at the turn of the century, some score of years before he came to live at Dedham, he took his father for a trip round some of his old haunts, staying at the Sun Hotel at Dedham, and meeting some of his old miller friends, including Alfred Chisnall at Brantham, Ebenezer Clover of Dedham, and James Boreham of Langham. And what great reunions they were, both there and at Sudbury and Colchester markets, and also at Mark Lane. | |

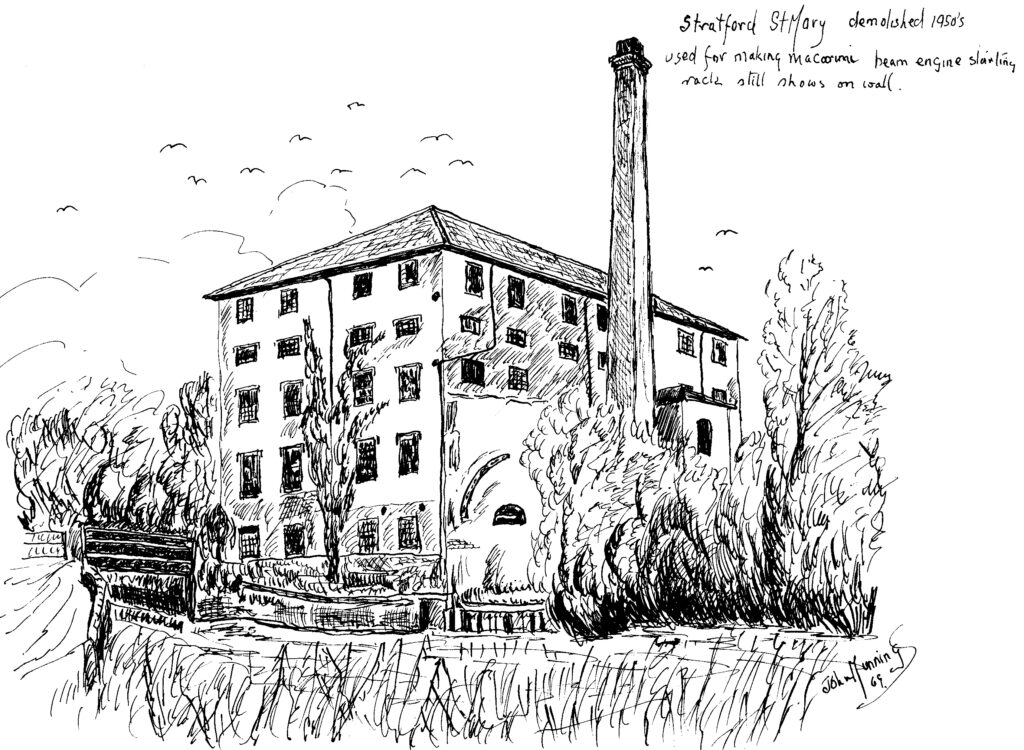

| I have vivid memories of this particular day, as on reaching Stratford Mill, a massive white brick and slated building, standing like decaying sentinel slipping into the river, disused for some thirty years, Uncle (the great orator that he was) started off. Did I know that one hundred years ago Constable sat on this very spot, painting his famous “Stratford Mill,” his finest painting, oh John why the H— weren’t we born a hundred years ago, (had that been so I no doubt would have been a miller, rather than a painter). Think of Constable sitting there painting to the sound of the mill, the steady lapping of the great wheel, and the humming of the machinery going on and on, the dusty miller looking out of the door, the horses and waggons going to and coming from the mill. The steady flow of the river, with its water-lilies and arrowheads waving in the stream. Horses hauling barges past on their way to Nayland and Sudbury, and going back down to Mistley. The river that gave full life to the valley in the every sense of the word. Boys fishing, the breeze catching the willow branches overhanging the river, and turning the leaves blue, silver, and mauve in turn, the swans and ducks, and every living thing, the cattle and horses grazing on the banks, what a world it must have been. This great sermon I never forgot. Today the great “Egyptian Temple” of a pumping station stands where the old mill was. | |