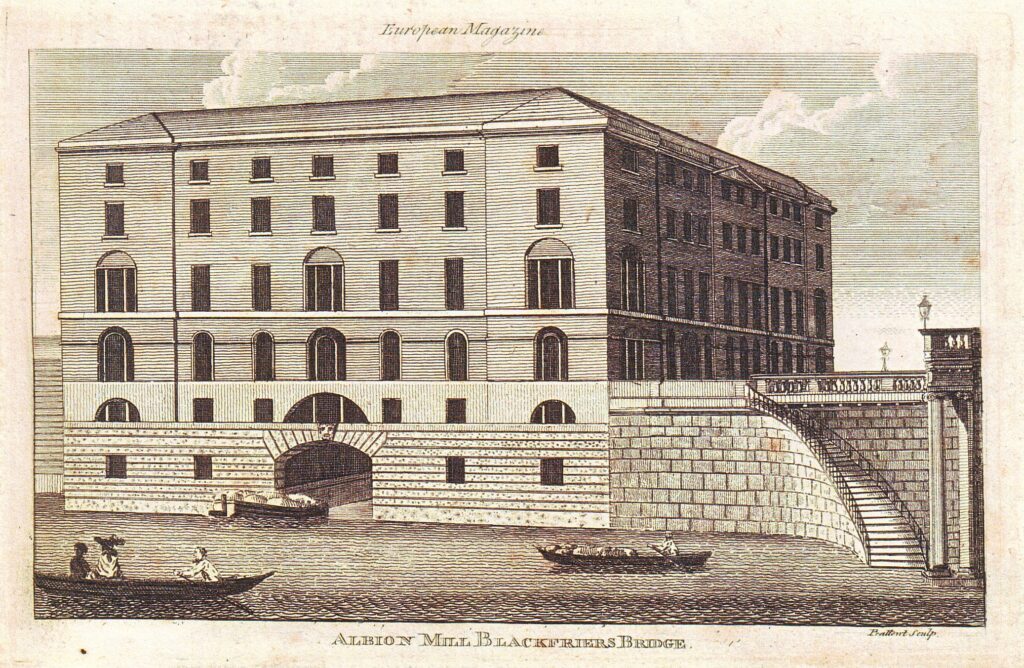

| Opinions are divided on the question of what the poet William Blake was talking about when he referred to the ‘Dark Satanic Mills’ that plague ‘England’s green and pleasant land’ in his famous poem, best known as the hymn ‘Jerusalem’. It is often seen as a reference to the Industrial Revolution, and some have linked the phrase to the first large steam powered flour mill, Albion Mills of Southwark, constructed in 1786 by Matthew Boulton and destroyed by fire a few years later. Its destruction was celebrated by London’s millers, who feared being driven out of business. William Blake was living not far away in Lambeth at the time, and the poem was published about a decade later. Others have suggested that the ‘mills’ are in fact the established church, or else that they are simply a part of Blake’s own complex private mythology. Whatever the original intent, the phrase has come to be widely used, usually to refer to workplaces where workers are exploited and mistreated. | |

(Mills Archive Collection, MWAT-018)

| While Blake gave us the memorable phrase ‘satanic mills’, he was not the first to connect the two ideas of milling and Satan. From medieval times millers had often been associated with the devil in popular sayings and folklore, perhaps because of their reputation as cheats and thieves who took more than their fair share of flour as payment for their work. As one Flemish proverb put it, Een voekeraar, een molenaar, een wisselaar, een tollenaer, Zijn de vier evangelisten van Lucifaar – “A usurer, a miller, a money changer and a tax collector are the four evangelists of Lucifer.” Legends and tales in which millers enter into pacts with the devil, are carried to hell, or use their cunning to sneak their way into heaven abound. Imagery connecting mills and devils could also be used symbolically, especially in religious polemic, and some examples can be seen below. | |

The devil becomes a miller

| In some stories the devil himself is a miller. A legend from Berry in France states that the devil examined all the trades to find the one where it would be easiest for an unscrupulous person to get rich, and decided it was milling. He built a mill on the river Igneraie, made entirely out of iron components forged in the workshops of hell. It was so successful that it drove all the millers in the region out of business. Once the devil’s mill was the only one left, he began to mistreat his customers so badly that St Martin of Tours, passing by and hearing their complaints, decided to act. It was the middle of winter, and St Martin built a mill upstream from the mill of iron. It was made entirely of ice. | |

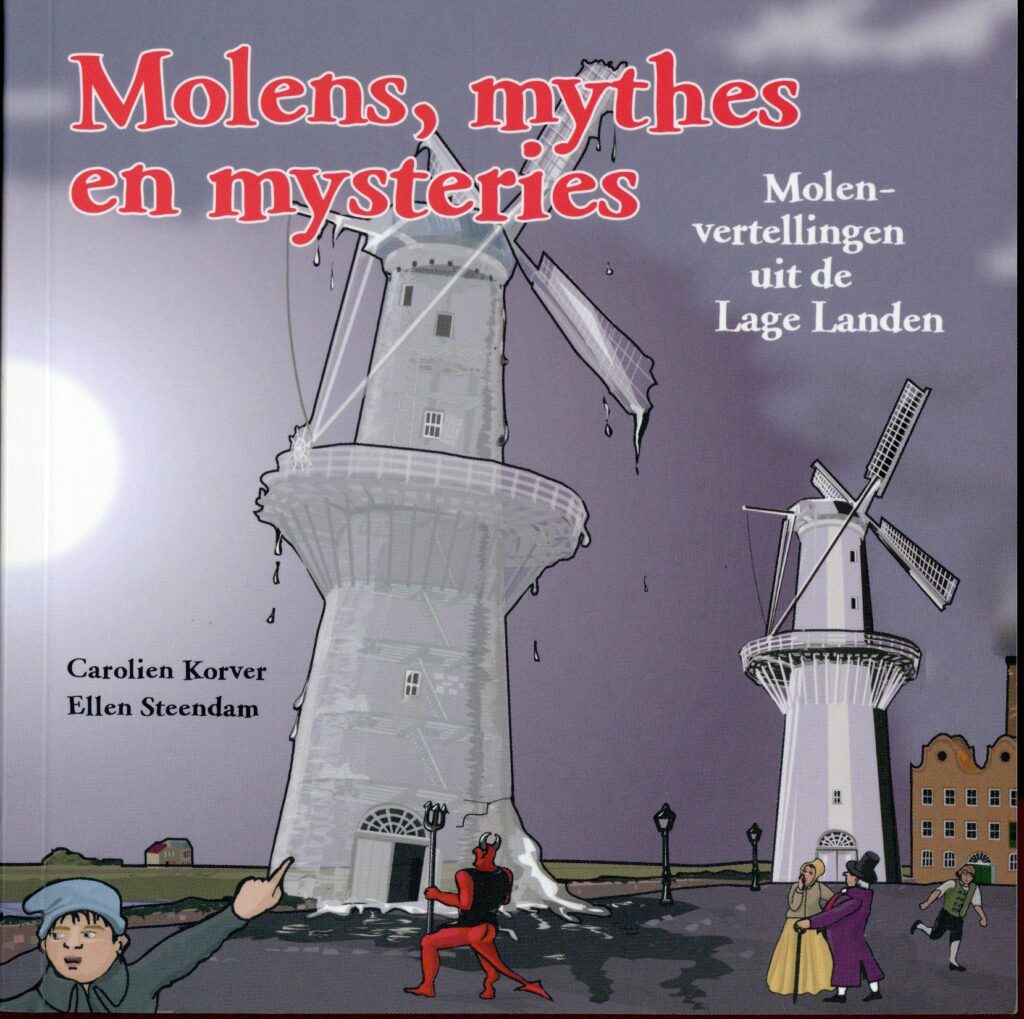

The cover of this Dutch book in the Mills Archive library shows a version of this story, although with windmills of iron and ice, instead of watermills.

| Everyone took their grain there to be ground, and they were so satisfied with the quantity and quality of the flour that the devil found himself without any customers. At last, the devil went to try and persuade the saint to exchange the mill of ice for his mill of iron. Saint Martin consented, but only once the devil had agreed to pay him an additional price of a thousand pistoles. This was the exact amount of money that the devil had cheated his customers out of. For eight days the devil worked the mill of ice, but on the ninth day the weather began to thaw, and the millstones no longer gave flour, but dough. This story and a number of others like it can be found in Légendes et Curiosités des Métiers (Legends and Curiosities of the Trades), written c 1880 by Paul Sébillot. Another folktale, the ‘Devil’s mill’, can be found on our blog: https://new.millsarchive.org/2020/06/02/the-devils-mill/?fbclid=IwAR3d7ohplQxTNd-R83kZk3369o6XMAsPygY4WFDoMznBBQbymuQi5PukLEQ | |

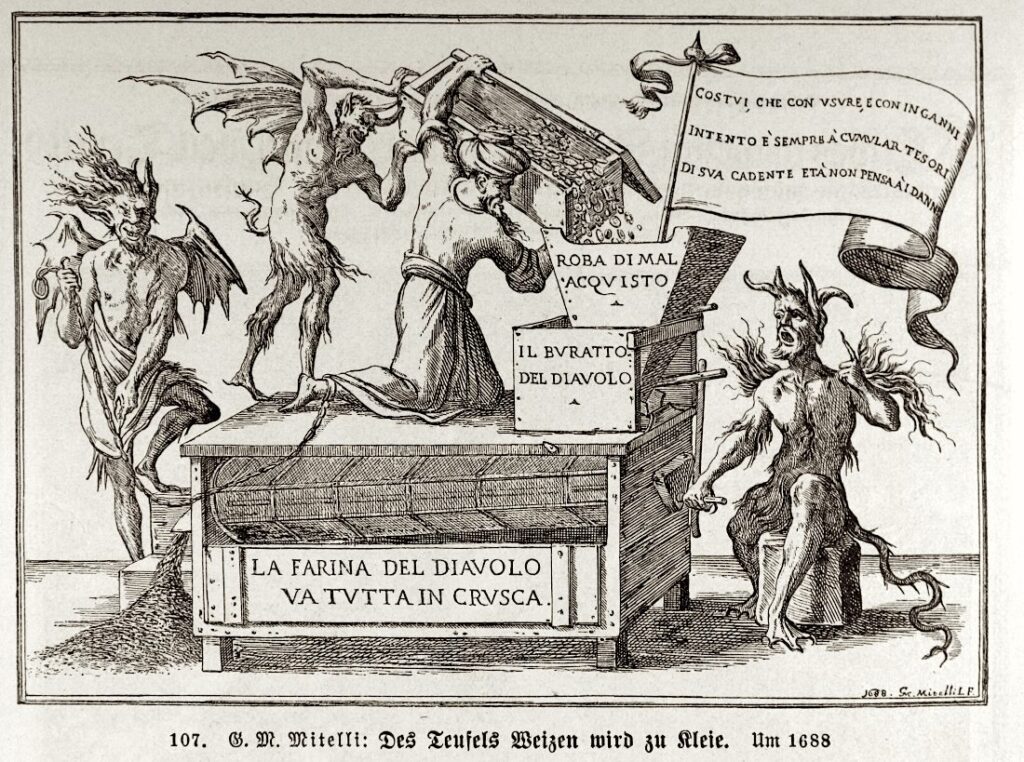

The devil’s sifter

| An Italian engraving of 1688, showing Il buratto del diavolo – the devil’s sifter. A sifter or bolter is used to separate the bran from the flour. In this case, however, the wealthy man is pouring his roba di mal acquisto – ill-gotten wealth – into the sifter, and as the message written on the sifter itself tells us, La farina del diavolo va tutta in crusca – the devil’s flour all turns into bran. The moral, given on the flag, is that wealth gained by deceptive means won’t last. | |

Mills of error

In religious controversy mills have sometimes been used as symbols of error or heresy. The image below, titled Moulin d’erreur is a piece of Catholic polemic against the teachings of the protestant reformer John Calvin.

Calvinism is represented by the post mill, its sails turned by devils, with Calvin himself sitting on the top. The mill is surrounded by a moat, beyond which are the towns of Nîmes, La Rochelle, Sedan and Geneva – all at one time protestant strongholds. But the bridges to these towns have been broken, and only that to Geneva still remains intact – indicating that this town is the only one still ‘buying the flour’ of false teaching.

media

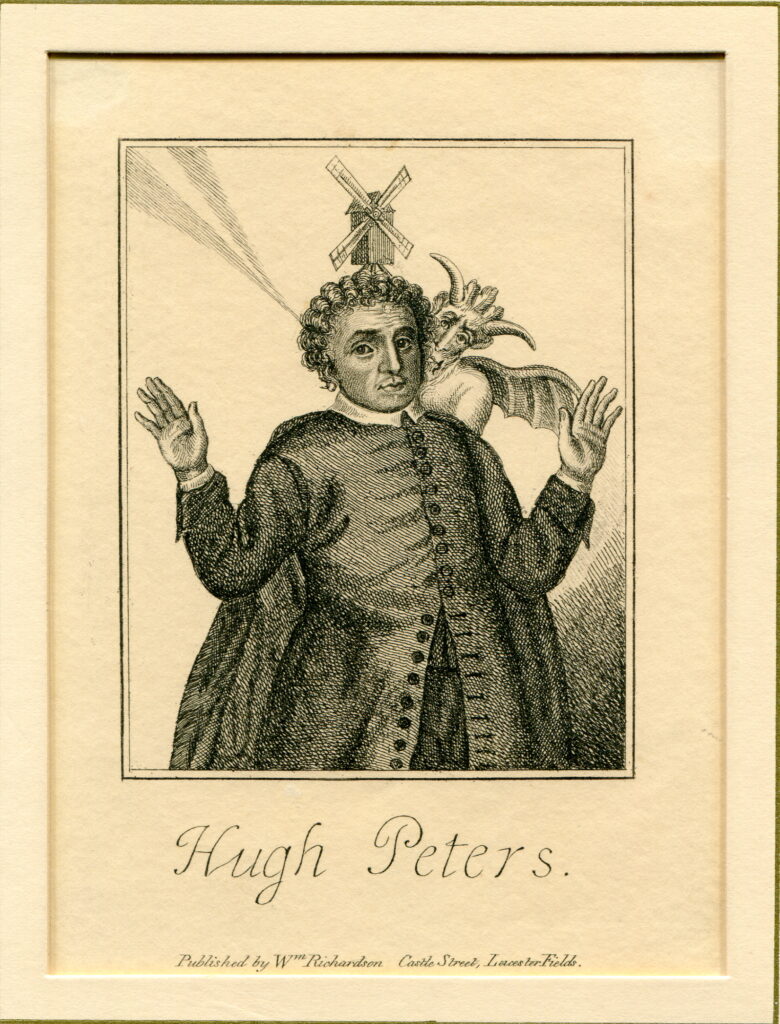

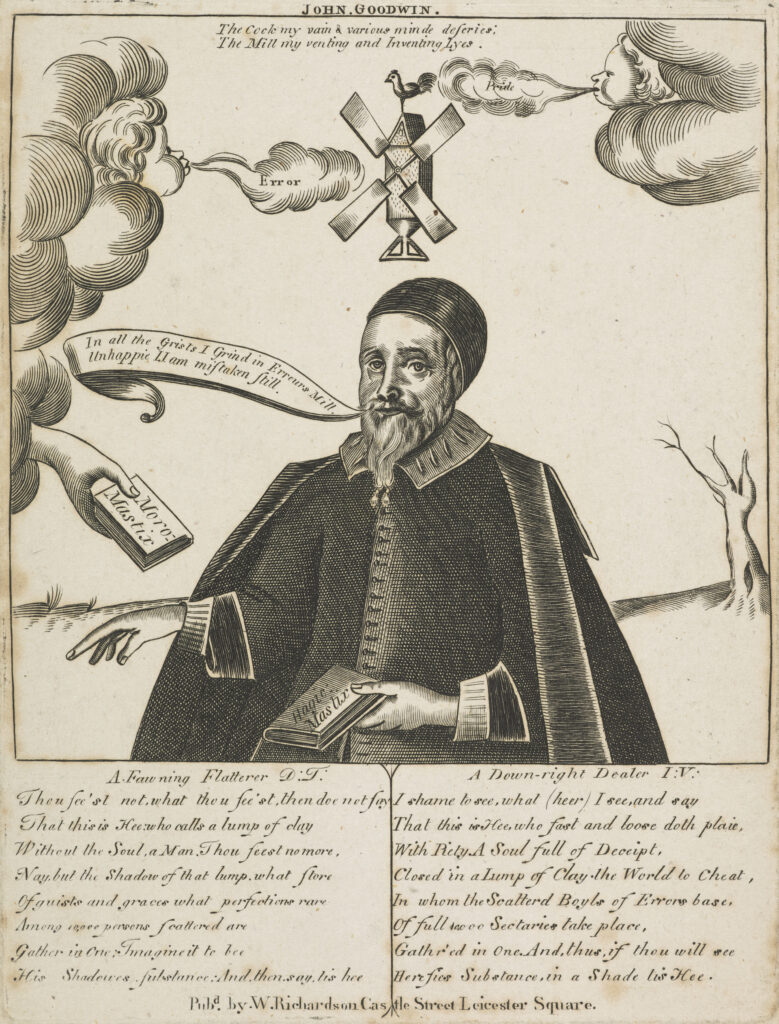

Another ‘mill of error’ is shown in this image:

Hugh Peters was a Puritan preacher who played a prominent role in the beheading of Charles I, leading eventually, after the restoration of the monarchy, to his own execution. The image comes from a broadside (an early form of printed leaflet) entitled ‘Don Pedro de Quixot, or in English the Right Reverend Hugh Peters’ – the windmill is a visual reference to the story of Don Quixote, and thus a way to imply that Hugh Peters has lost his mind. This appears to have been a standard part of the iconography of satirical engravings in this era – another example, although without the devil, is found in the image below.

Mildred Cookson Collection. A slightly different version is held by the British Museum: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1848-0911-505

media

This image shows John Goodwin, another controversial preacher of the same period. The speech scroll coming from his mouth reads “In all the Grists I Grind in Erreurs Mill/Unhappie I. I am mistaken still”, while above the winds of ‘pride’ and ‘error’ power the mill.

Image from National Galleries Scotland: https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/30816/john-goodwin-c-1594-1665-republican-divine-and-controvertialist

Mills in hell

| Don Quixote mistook windmills for giants; Dante in the Inferno made the opposite mistake. Descending into the ninth and lowest circle of Hell, he sees something looming in the distance, “just as, when night falls on our hemisphere, or when a heavy fog is blowing thick, a windmill seems to wheel when seen far off.” But drawing closer he discovers it is not a windmill but Satan himself – what he had taken for windmill sails being the six wings which Satan beats continually, creating the icy wind which freezes everything. Visions of the horrors of hell were a popular theme in medieval art – another appearance of mills in hell can be found in the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights by Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch (c 1450-1516). His vision of hell, shown on the third of the three panels that make up the painting, is full of bizarre and grotesque imagery, but see if you can spot the mills: | |

| They are in the distance – both a watermill and a post mill are shown, on either side of a river: | |