| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this summarises Chapter 11. The article written in 2016 is helpful summary of the revolution in the UK during the preceding 100 years or so. Since then the pace of change has increased and much consolidation has been possible as processes become ever more efficient. | |

Readers of the journal Milling and Grain https://millingandgrain.com/ are well aware of the pace of change and the importance of these changes to milling around the world. Nataliya is capturing some of the articles from that journal for our library https://new.millsarchive.org/search2/?class=PublicationInLibrary&match=all&criteria=Publisher%7Eequals%7E1094 and has already uploaded more than 260 digital articles from the last four or five years – with a lot more to come! Well worth a look!

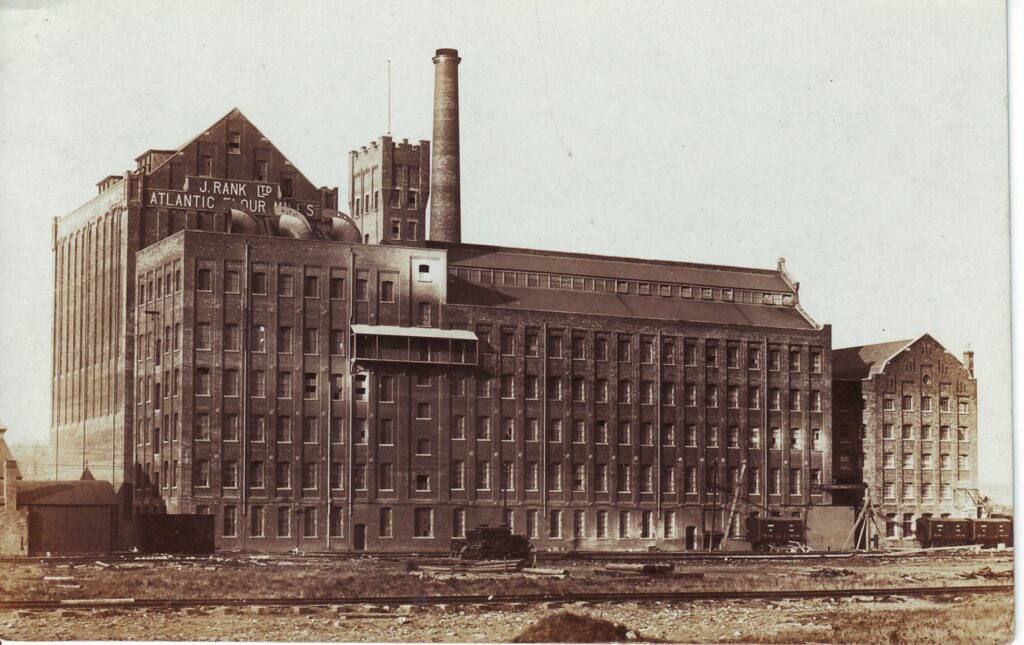

| The first decade of the 20th century was marked by the construction of a number of large new roller mills such as Joseph Rank’s Premier Mills at Victoria Docks in London and Atlantic Mills, Barry Docks in Cardiff, Vernon’s Millennium Mills, also at Victoria Docks, and, at the Manchester end of the ship canal, Baxendell’s Sun Mills, which were subsequently acquired by the Cooperative Wholesale Society (CWS). Also built at this time were Marriage’s East Anglia Mills at Felixstowe, Hovis Bread Flour’s new mill at Trafford Park, Manchester and the Cooperative Wholesale Society’s Silverton Mills, London and Avonmouth Mills, Bristol. Other established mills such as the North Shore Mills, Liverpool and Regent Mills, Glasgow were remodelled. The three main suppliers of roller milling machinery continued to be Thomas Robinson & Son of Rochdale, E.R. & F. Turner of Ipswich and, in particular, Henry Simon of Manchester. By 1914 the CWS together with Spillers and Ranks, who were in the process of building Ocean Mills at Birkenhead, Cheshire, had risen to become the key players in the industry. | |

| During the First World War the production and distribution of flour came under government control, a situation that lasted until 1921. With de-control came a period of competition and reorganisation. Some companies had lost trade during the war and were now seeking to regain it, but others gained new customers during the war and increased their production as a result. Over-production and imports of foreign flour added to the mix. Two of the main players continued to be Spillers and Ranks. By 1924 Ranks had the controlling interest in at least eight other sizeable companies, in addition to its own mills, while Spillers controlled seven, manufacturing not only bread flour but also a range of other cereal products including dog biscuits. | |

| In 1929 the Miller’s Mutual Association was formed through which flour output quotas were fixed and funds raised to buy out and close redundant mills. This resulted in the larger milling companies acquiring smaller milling concerns and taking over their quotas. By the end of 1933 Ranks controlled some 15 to 20 companies including the Associated London Flour Millers (ALFM), which had seven London mill members. By the start of the Second World War there were only about 500 mills producing flour in the United Kingdom, of which half were small, independent businesses. The three largest companies, Ranks, Spillers and CWS, now produced two-thirds of the country’s flour output. All three invested in large mill projects in the 1930s, with the CWS claiming the title of ‘Britain’s largest mill’ when their Sun Mills, Manchester was remodelled. The milling industry came under state control again at the start of the Second World War, a situation which lasted until 1953. All millers had to obtain a licence, the distribution of grain and flour was regulated, and prices were fixed. | |

| Many port mills suffered bomb damage during the war. Amongst the victims were the Millennium Mills in London (by then part of Spillers), which had been damaged previously in the First World War following an explosion at a nearby munitions factory. Rank’s Premier Mills close by were also destroyed, as were their Ocean Mills at Birkenhead. Not surprisingly, the post-war period was witness to a large rebuilding exercise. Robinsons and, in particular, Simons were the suppliers of machinery to many of these new mills. The progress of stock and flour through the mill became more automated with the introduction of pneumatic conveying systems. Stock transported through metal tubing, which superseded wooden spouts, elevators and conveyors, remained cooler, cleaner and less susceptible to infestation by meal moth. Plansifters also finally took over from centrifugals as the principal means of dressing flour. Plansifters, which were developed in the late 19th century, although anticipated by a form of sieve patented in the 18th century, comprised stacks of sieves in a horizontal plane, in contrast to the rotating sieves of centrifugals. Other changes were also afoot as the milling and baking industries became closer entwined, enabling greater control of production from grain to loaf. Both Ranks and Spillers bought into baking companies and, conversely, in the early 1960s Allied Bakeries Ltd moved into the milling industry, acquiring 30 mills. The Millers Mutual Association continued to buy out smaller companies with the net result that the number of flour mills in Britain steadily declined. The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the merger, acquisition and reorganisation not only of a number of the long-established milling companies such as Ranks, which became Rank Hovis McDougall Ltd in 1962 and then became part of Premier Foods, but also in the engineering companies that supplied them. The Robinson Group acquired Simons in 1988 and in turn became part of the Japanese Satake Corporation in 1991. At the time of writing (2016) there are less than 30 roller milling companies operating 52 mills, with the four largest concerns accounting for 65 per cent of the UK’s flour production. But there are still a number of smaller milling companies, including family run businesses such as Marriages, which was first established in Essex in 1824. Modern flour milling, from the unloading of the grain upon delivery into silos to the sacking and packing of the finished products, is one of the most highly mechanised, automated and efficient modern industries. Indeed one of the most notable developments over the last 50 years has been the increasing amount of automation. Computer technology was first used in the late 1970s and today all aspects of the roller milling process can be remote controlled, enabling precise adjustments and alterations to be made to produce the required result. Correct management of the raw material remains a key part of the process. The grain is tested upon intake to ascertain such aspects as weight, moisture and protein content. To prepare it for milling, the grain is cleaned to rid it of all impurities and dirt and then conditioned by introducing water to soften the bran layer, the amount of water required being determined by the moisture content of the grain. It is then rested for up to 24 hours before milling. Different wheats may also be mixed together prior to milling to produce a particular grist, depending on the final product required. | |

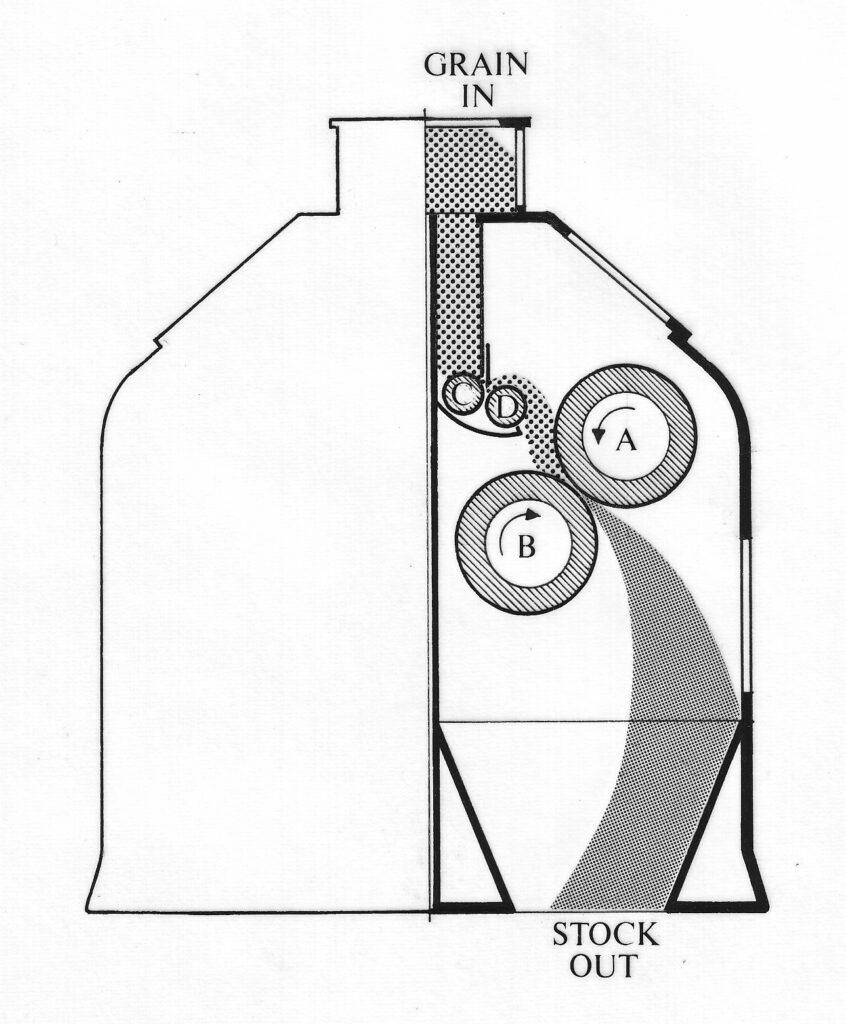

Section through a roller mill. Each unit is divided into two halves which can be used on separate runs. A is the fast roll, B the slow, and C and D the feed rolls.

Section through a roller mill (Mills Archive Collection, MWAT-030)

| Roller mill buildings are usually between three to six storeys high and generally all machines of the same type are located on the same floor. The basic roller mill unit comprises a pair of chilled iron rolls set less than a grains width apart. The lower roll runs more slowly than the upper, catching hold of the grain while the upper, faster roll cuts it. The modern mill uses two sorts of rolls: break rolls, which have slightly spiralling longitudinal saw-toothed fluting, and smooth reduction rolls. The fluting on the break rolls cuts open the grain and scrapes the endosperm from the bran. The broken grain is sifted, graded and purified after each break in order to separate the different ‘streams’ of partly milled endosperm (semolina), germ, bran and a small amount of white flour. The semolina is then passed through a series of reduction rolls which gradually reduce the endosperm particles to the required fineness of white flour. Again the ground product is sifted after each reduction to remove the flour. At the end of the process different streams may be blended to produce different flours. The best quality white flour derives from the early streams, while wholemeal comprises all the streams including the bran and germ combined together again. A mill may have up to four break rolls and twelve reduction rolls on each run. The milling industry has come a long way from a hand-operated saddle quern serving a family or small group of people, to a fully automated, computer-controlled milling process that is capable of grinding some 320 tonnes of wheat a day. The principle of cereal grinding, however, of breaking open hard grains and refining the starchy centre to produce a usable food product, remains essentially the same. | |