| The articles on which this newsletter is based first appeared in Mill Memories 26, Spring 2020 and 28, Spring 2021. Millers need to keep up with each other with all phases of manufacture and distribution. Whilst packaging is not an integral part of the operation of turning wheat into flour, nevertheless, had it not progressed with other milling improvements, the industry would not have been able to keep up efficiency. | |

Roll out the Barrel

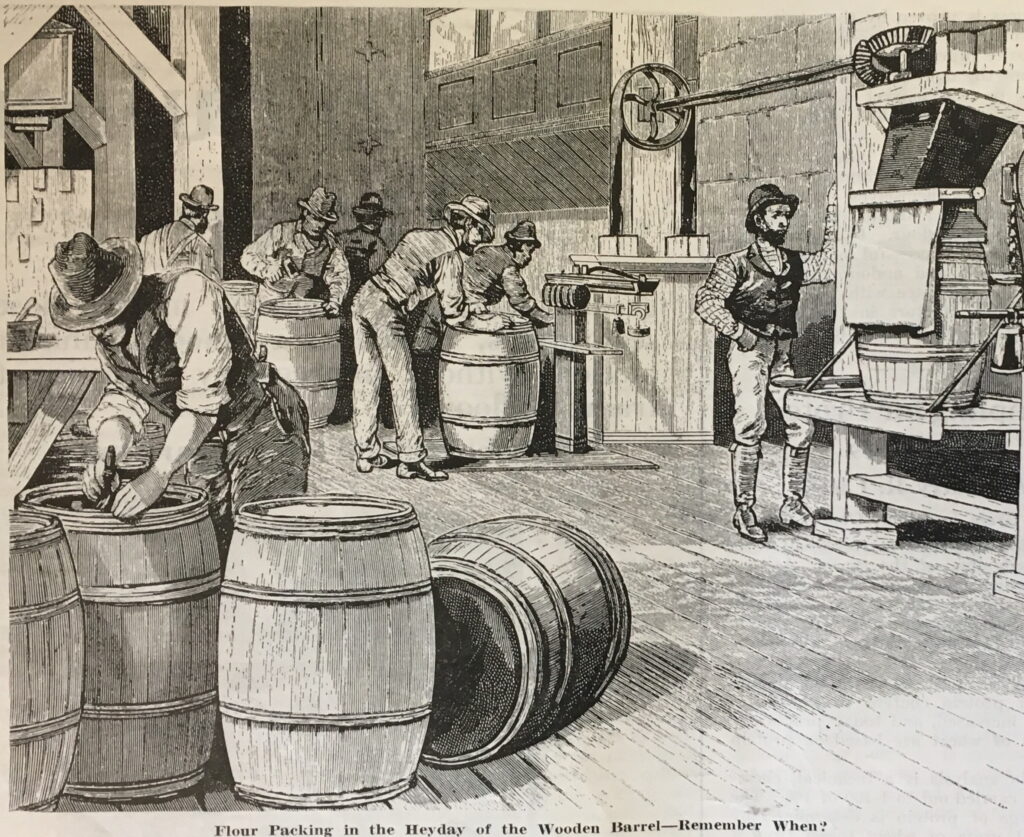

To trace the development of modern flour packaging, we have to go back to the wooden barrel.

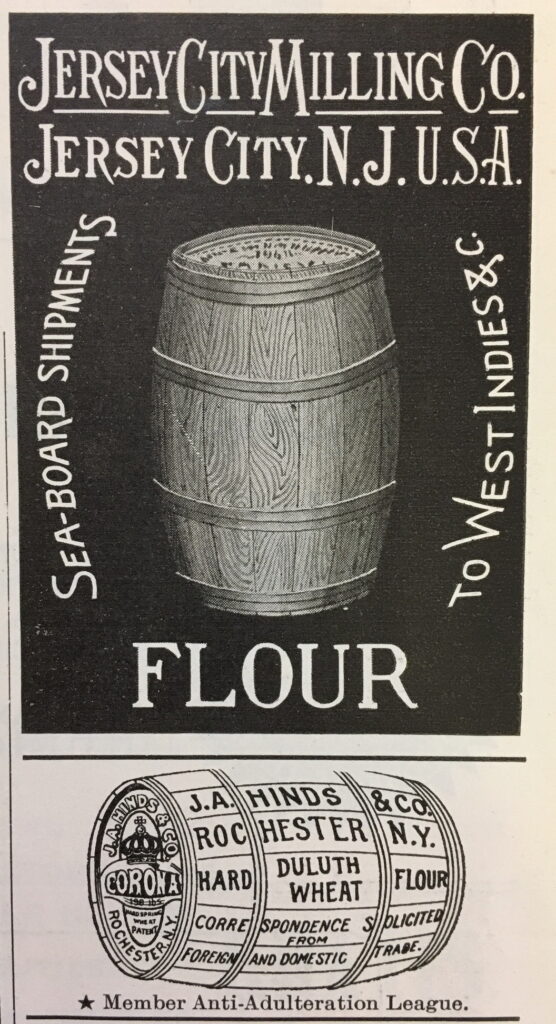

| For years this was the standard container of the industry in the USA, and whilst today it is almost non-existent, its influence is still shown by the fact that flour quotations are usually made on a ‘per barrel’ basis. | |

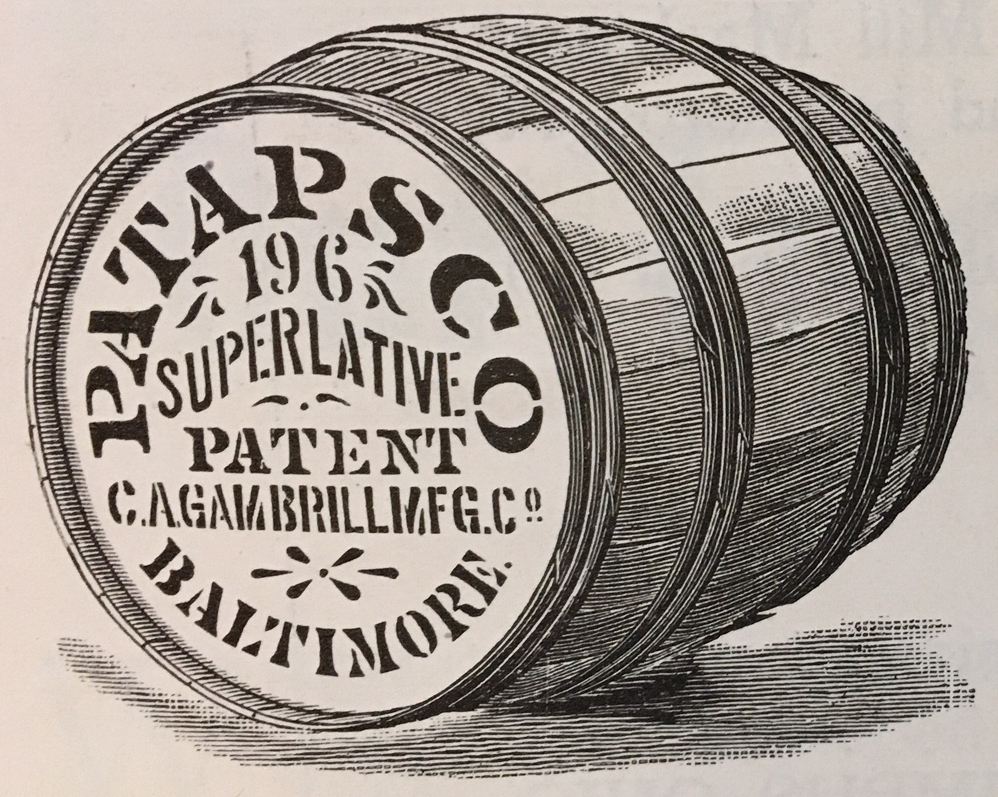

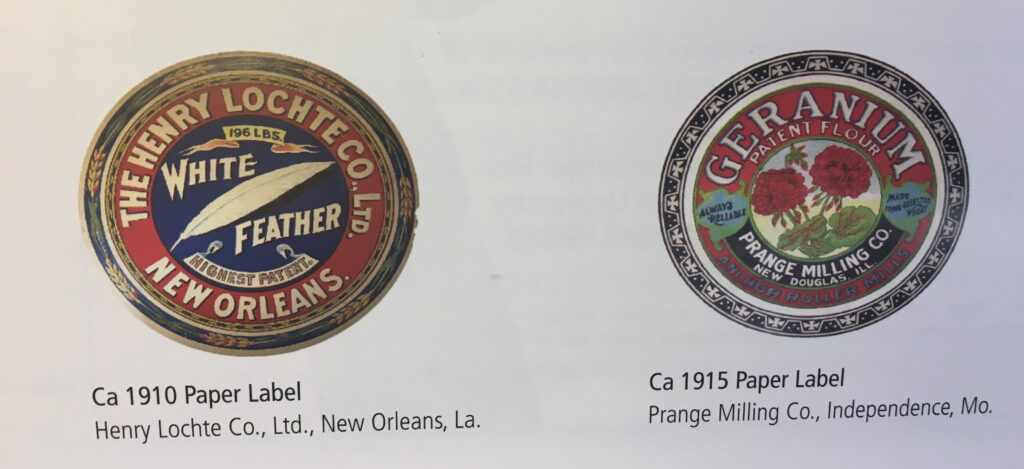

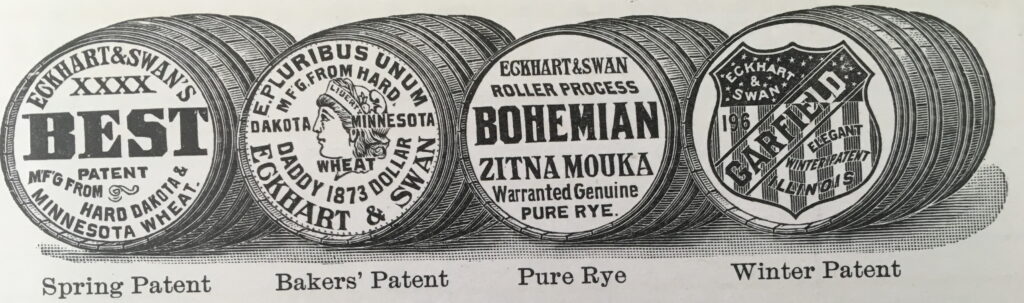

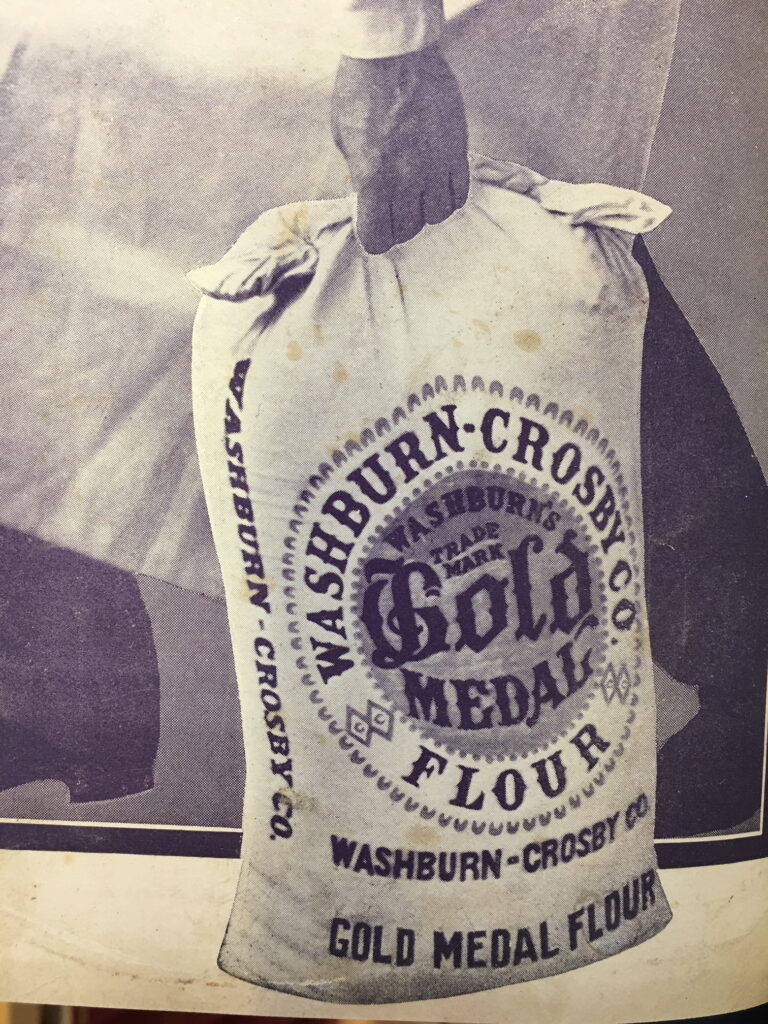

| A miller’s mark of origin was applied to a barrel as a sign of ownership and was done with a ‘branding iron’. The miller’s name, mill location and the intended weight of a filled barrel would be burned into one or more of the barrel staves. This practice quickly gave way to stencils for inking the information on to the barrel staves or the flat surface of one or both ends of the barrel. The final stage was the use of paper labels on one end only. The circular design on the end of the barrel was continued for trademarks and logos on cloth and paper sacks. | |

| During the period of its greatest popularity, the barrel served its purpose well and efficiently. Conditions in the milling industry were entirely different than they are today. Shipments were slow and hazardous, consumers bought supplies of flour for months in advance. Merchandising practices were comparatively simple, and the barrel was exactly what it was supposed to be – a container. | |

| The demise of the barrel as an approved flour container came primarily from two causes, the development of other packages, such as jute, cotton and paper, and altered purchasing habits by American consumers where much smaller units of flour were wanted. This resulted in the complete revolution of flour packaging methods. | |

Getting the sack

In developing a suitable change in the packaging, thought had not only to be given to what material to use, but also to the machinery needed to fill them.

asa

Other food manufacturers were making rapid advances in packaging to sell their products in efficient and attractive ways.

When the decline of the wooden flour barrel set in, jute and cotton bags rapidly took their place. Bags made from these materials were already in use for other industries and they adapted well as flour containers.

American wheat imported into the UK sometimes came over in jute sacks and I myself would re-use them in the mill. With an abundant supply of cotton and the fact that they suited the purpose of a flour sack, it seemed only natural that these would have a widespread use. They were economical, and could be re-used. The stage was reached whereby the filling and closing of the sacks had been brought almost to an exact science.

M Cookson. Grain sack coming through trap doors, Mapledurham Mill, Mapledurham

(MCFC-1122134-04, Mills Archive Collection)

| Improved printing processes meant that several colours could be printed on them with inks that would, after many washes, remove all trace, so adding to the sacks reuse value. During the Depression many families used cotton flour bags and feed sacks to make not only clothes, but curtains and other household items including nappies. Once the manufacturers cottoned on to this they began decorating them. The Percy Kent Bag Company even hired top textile designers from Europe and New York City to create stylish prints. | |

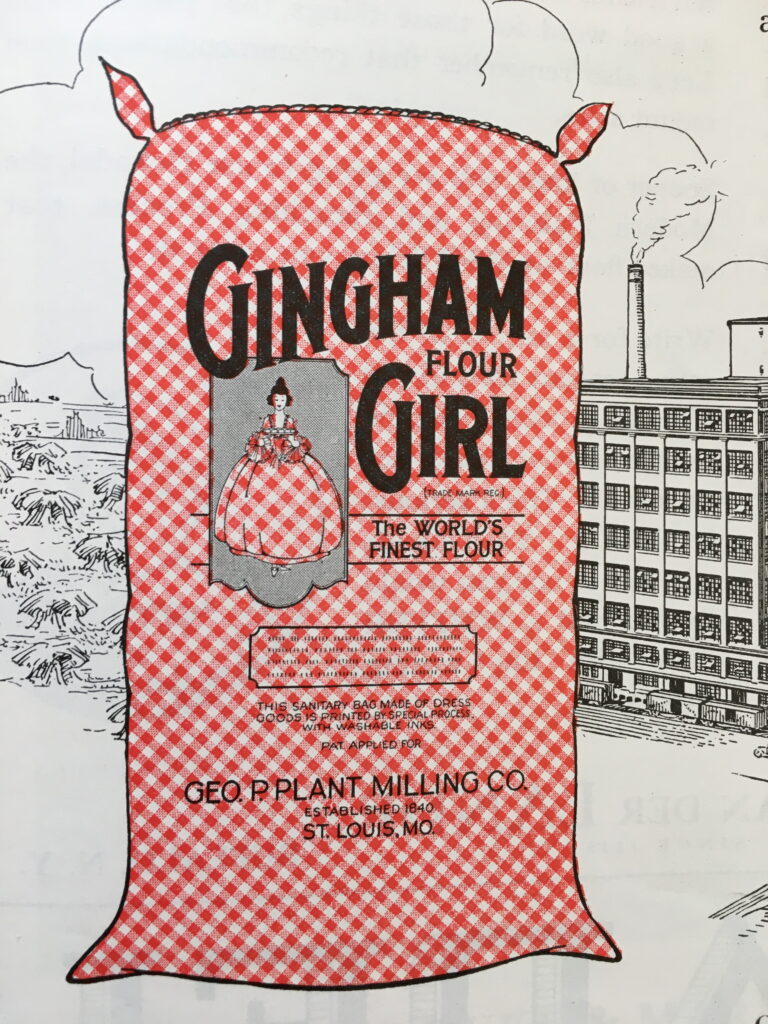

In 1927 three yards of printed cotton percale could cost 60 cents in the shop, and three yards of gingham 40 cents. In comparison, three yards of gingham, used in the Gingham Girl Flour sacks, from the George P. Milling Plant Company, would make a dress from two or three 100lb. flour bags. The flour bags were free, but required a lot of baking! These new cotton flour bags could be displayed on the retail shop shelves helping to promote each particular brand of flour.

Moving on to paper bags, it was thought that this was first used by grocery stores, who formed ordinary paper into the shape of a bag and tied it together at the top.

If

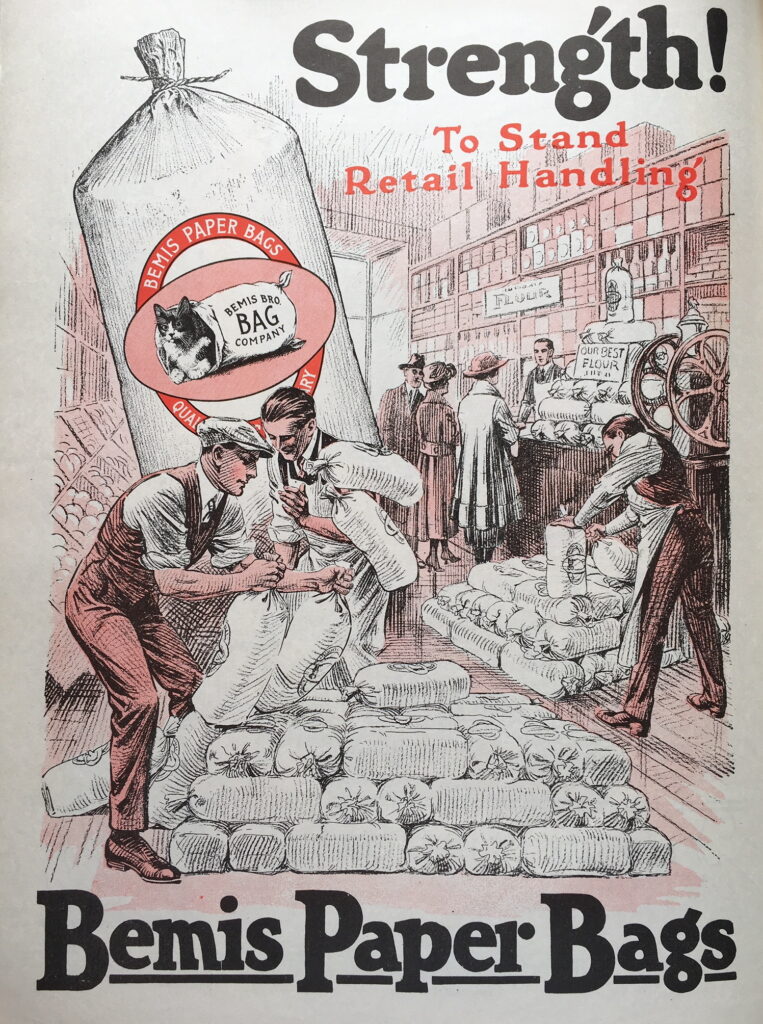

| The next step appeared to be an envelope type of bag which was glued against the leakage of flour or other powdery products. After this came the ‘satchel bottom’ which not only provided a tight container, but could be made to stand alone within a display. It was easily filled with a machine for this purpose and as the surface was smooth it made a better surface for the advertising of the product. | |

| The most difficult problem was the type of paper to be used for flour. It has to be light and yet strong. The size also played an important part, bakers still however, required the larger sacks, but the average household demanded a smaller size. This of course had an impact on the mill’s production line. Filling and handling of the new sizes had to be sought. Nowadays this has been perfected regardless of size of bag so from the start of the operation to the finished closed bags, all can be carried on conveyers to any point in the mill. | |