| The mill as a metaphor for time and change is an ancient theme. St Augustine of Hippo (354-430) in his ‘Expositions on the Psalms’ described the world as a mill, because of the way the wheel of time is ever revolving and in the end crushes everyone. The ancient Greek proverb dating back to at least the 1st century expresses a similar idea – ‘the mills of the gods grind slowly, but they grind fine’, i.e. justice will in the end be served, however long it may take. It was rendered into English by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) as: Though the mills of God grind slowly; Yet they grind exceeding small; Though with patience He stands waiting, With exactness grinds He all. St Augustine’s image of the mill as representing the endlessly revolving activities of the world was taken up by later religious writers, such as the 12th century French monk Gérard Ithier who wrote that “the mill signifies the unstable movement of the world full of continuous upheavals, disturbances and tribulations.” The endless revolving of millstones reflects the endless change and turmoil of the changing world – for the religious writer, something to be contrasted with the peace and tranquillity found in the monastery. |

The mill of life

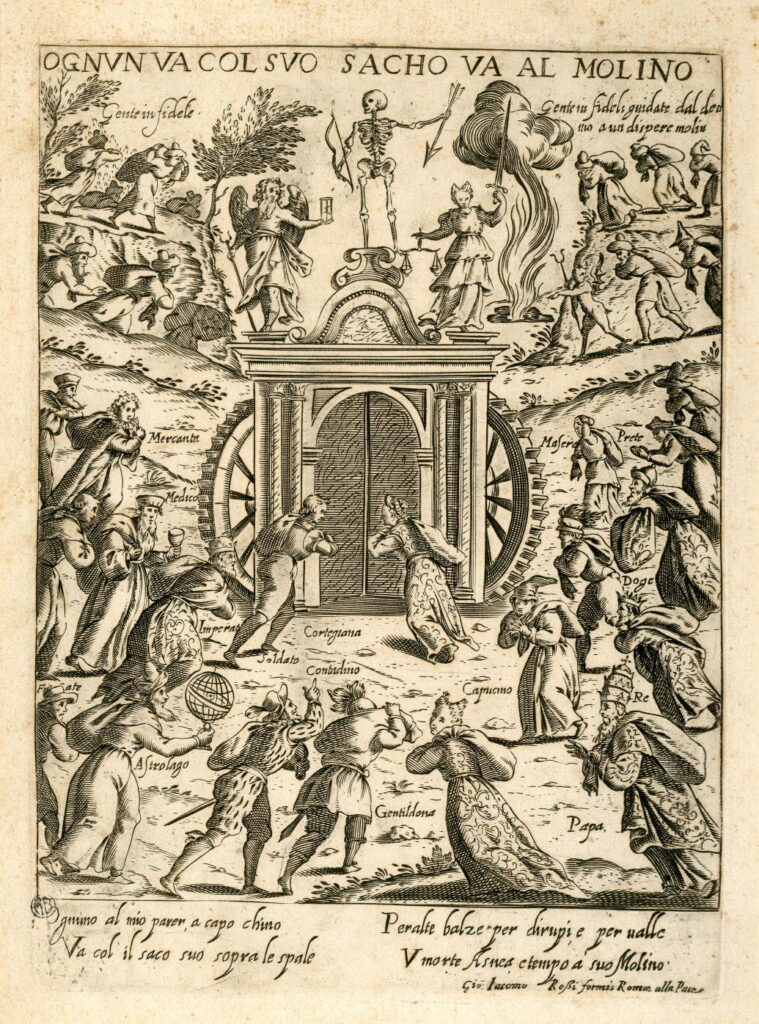

| We can see a further variation on the theme in this 16th century engraving from Milan titled “Ognun va col suo sacho va al Molino” – each one goes with his sack to the mill. The mill, which seems to represent life, is guarded by three figures who would seem to be Father Time with his hourglass, Justice with her scales and Death. In the foreground people from every walk of life take their sacks to the mill, including a merchant, a doctor, an astrologer, a pope, a king, a gentlewoman, a monk and a priest. |

The old miller and his mill

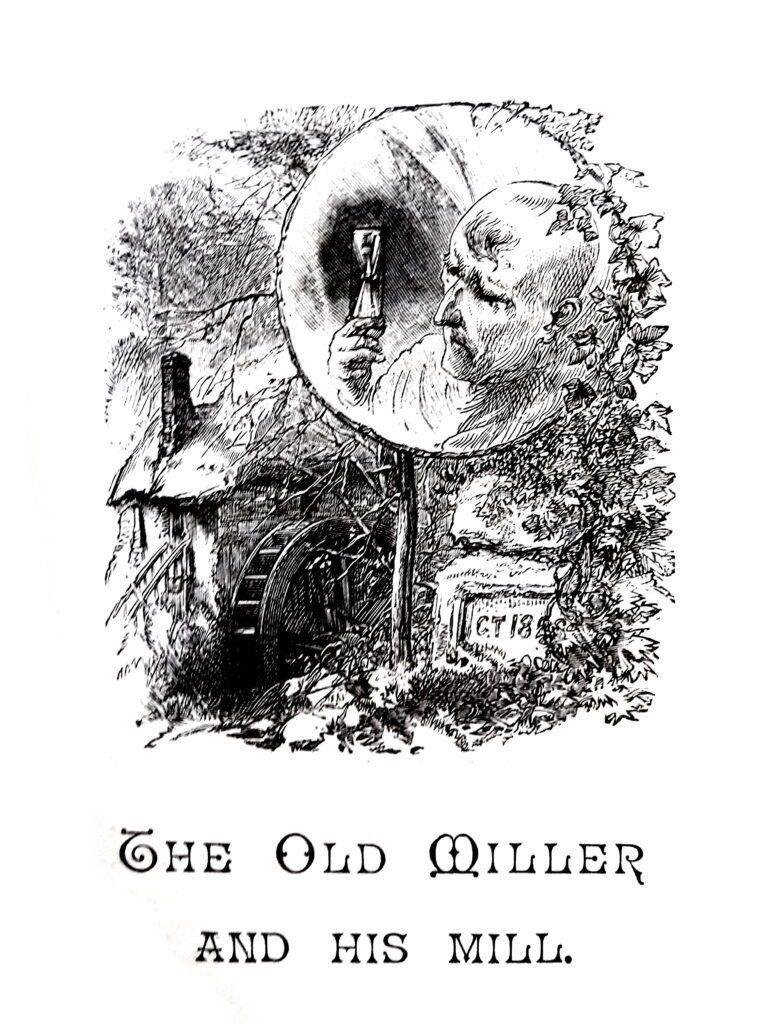

Father Time also appears as a miller in a children’s story titled “The Old Miller and his Mill” by Mark Guy Pearse published in 1891, a copy of which is in the Mills Archive library. The old miller, who nobody has ever seen, and who never stops working day and night, grinds at a wonderful mill full of wheels:

…big wheels and tiny wheels as small as those in the inside of a watch! The biggest wheel was so big that it took a year to go round. And this turned more than three hundred smaller wheels. Each of these turned twenty-four smaller ones; and those four-and twenty, every one of them turned sixty little tiny wheels. And every little tiny wheel turned sixty that were tinier still. Now, if you take the trouble to put all that down you will see that it comes to more than thirty-one millions of wheels. And yet never a wheel got out of order; his mill was never even stopped for repairs.

But what did he grind with all these wheels? Ah! I think you never would guess that.

He ground BABIES.

In they went – no-year old babies, and one-year old babies, two-year old babies and three-year old babies. Rich people’s babies smothered in lace and ribbons; and poor people’s babies that looked quite as pretty and laughed as merrily – in they went into his mill.

…then all the wheels began to go round; the tiniest wheels of all, and then the next, and the bigger and the bigger still, and at last the one great big wheel of all. And when that had gone round a few times the old miller’s wares were ready. No more babies, no more boys or maidens. They were all men and women.

| The following chapters of the book, with titles like ‘The mill that ground cross folks’ and ‘How the babies were ground into gentle people’, use the milling theme to present the lives of various Biblical characters, either as examples to be emulated or cautionary tales about vices to avoid. |

The mill of the years

| A final example is this poem from the American milling journal the Northwestern Miller (1887, reprinted in 30 Dec 1942, p.20): THE MILL OF THE YEARS Old Time, in his wonderful Mill of the Years, Grinds daily an output of joys and of tears; And the sum of his grist for the year passing by, Now almost complete, is recorded on high. The good deeds, the bad ones, the gainings and winnings, The partings and meetings, the virtues and sinnings, Have all gone, perforce, through this terrible mill, And the hopper of Time is unsatisfied still. The good deeds grade Patent; you usually find That forty per cent is the most these mills grind. Of fair words and intentions, Time makes a Straight grade, And regretfully notes ’tis the bulk of his trade. His Bakers’ he gleans from the best that he can And his Red Dog [the lowest grade of flour] is made from the weakness of Man. In the Offal and Waste go the crimes and the sins, And are spouted, they say, to some very warm bins. The experts declare that Time’s system is poor- That the Mill of the Years’ somewhat ancient is sure- But Head Miller Death is a hard one to beat; He says that the mill’s not in fault, but the wheat- That the All-Wise Millbuilder, who laid out the plan, Made the very best mill e’er constructed for man. That its system is perfect, machinery fine, Not a spout out of place, not a shaft out of line; In short, that the mill every way is first class, But the stuff that is ground in it’s lacking, alas! That the good Human Wheat is so mixed up with lies And Satan’s own Cockle, ’tis quite a surprise That the Mill of the Years doesn’t grind all low grade, For the exclusive use of a tropical trade. Be that as it may, grinds this mill day and night, With an awful, resistless and terrible might; And ever shall grind until Time from his store Shall exhaust the last year, and exist nevermore. WILLIAM C. EDGAR |