| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this summarises Chapter 9. For a much more detailed treatment read the article itself. |

| The century between 1750 and 1850 was one of great social change as Britain moved inexorably towards industrialisation. The period was also marked by a huge increase in agricultural production and a massive rise in population. This led to a corresponding need for increased grain processing and yet at the same time there was increasing competition for water-powered sites from other industries, particularly the textile industry. Consequently the later 18th and earlier 19th centuries saw a notable rise in the number of windmills. |

| Amongst the many windmills built or rebuilt during this period were tower mills at Heage, Derbyshire (c.1791), Marsh Mill, Lancashire (1794), Brixton Windmill, Surrey (1816), Maud Foster (1819) and Heckington windmills (1830) in Lincolnshire and Stevens’ Mill, Burwell, Cambridgeshire (c.1820) and smock mills, such as White Mill at Sandwich, Kent (1760), Upminster, Essex (1803) and Wicken, Cambridgeshire (1813). A feature of most windmills is that they need to be turned to face the sails into the wind. Edmund Lee’s 1745 patent drawing for a self-regulating windmill shows a fantail which, in theory would automatically bring the sails into the wind again. In 1782 John Smeaton in his design for Chimney Mill, Newcastle-on-Tyne, included a fantail which was set on a small stage attached to the back of the cap. Fantails were also used on post mills, sometimes mounted on a carriage at the rear of the mill, similar to Lee’s original design. |

| Other improvements to windmills were made, to counter the effects of changes in wind force as well as direction. The introduction of the governor, probably in the 1760s, allowed the miller to regulate the gap between the stones, enabling the consistency of the ground product to be maintained automatically regardless of wind speed. |

Various advances were made in the design of windmill sails, culminating in 1807 when the Norfolk engineer William Cubitt took out a patent for what became the most prevalent of all the self-regulating sails, now known as the patent sail. Cubitt combined features from several earlier designs, connecting all the shutters on each sail with a rod which in turn is linked by a crank to another iron rod – the striking rod – which passes through the centre of the windshaft. By moving this rod backwards or forwards, using a chain connected to it, all the shutters could be opened or closed remotely, without stopping the mill.

| The pressure on millers and mill owners from the increasing use of water power by other industries meant they needed to make the best possible use of the available resources. Attention was turned to improving the construction of waterwheels to make them more powerful and efficient. High-breast and pitchback waterwheels set in close-fitting curving masonry breastwork became more common, both types having the advantage in that they turn in the direction of water flow and so their rotation is unimpeded by tailwater. |

| In addition to improved waterwheels, larger mill buildings were also being built. Eling Tide Mill and Chesapeake Mill in Hampshire, Gleaston Mill, Cumbria, Carew, Pembrokeshire and Redbournbury, Hertfordshire, for example, were all rebuilt in the late 18th or early 19th century. Other mills were extended, sometimes by the addition of an upper storey. These mills typically now had three or four floors providing room for grain storage, cleaning, grinding and dressing. |

| Improvements were also made to both the grinding performance and the output of millstones, to ancillary machinery for cleaning the grain prior to milling and for dressing the ground meal to produce white flour, the demand for which was steadily rising. A millstone ventilation system, similar to that based on a French design which was installed by Potto Brown at Houghton Mill, Cambridgeshire, was patented by George Hinton Bovill in 1846, for it was found that millstones worked better when they ran cool. There was also a notable increase in the use of French millstones, which became widespread for milling wheat. When well-dressed these stones remove the bran from the endosperm in large flakes which are easier to sieve out, enabling a whiter flour to be extracted from the resulting meal. Winnowing and threshing machines were introduced in the late 18th century and it appears that the first grain cleaning machines in mills date from about the same time. Rotary cleaners were developed in the 19th century, comprising a horizontal wire mesh cylinder into which grain was fed and forced against the mesh by rotating brushes or beaters. Cockle cylinders were used to remove unwanted weed seeds by size difference and in the later 19th century vertical smutters, which scoured the grain to remove a type of fungus known as smut, were introduced. Similarly, flour bolters which separated fine white flour from the bran did not become common in mills until the 18th century. The success of these and further technological developments depended much on the use of cast iron. John Smeaton pioneered its use for wind- and waterwheel shafts and by the end of the 18th century it was also used for gearing, initially for smaller gears but, as founding techniques improved, so larger gears were also cast. Smeaton also designed a cast-iron cross attached to the end of the windshaft to which five or more sails could be fitted rather than the more usual four. Many five- and six-sailed windmills were subsequently built in northern and eastern England. Heckington windmill in Lincolnshire was originally built as a five-sailed mill in 1830 but was repaired after storm damage in 1892 with eight sails. In the 1830s the Scottish engineer William Fairbairn introduced cast-iron standards for supporting millstones and their driving gears, such as were installed in Park Mill, Brereton in Cheshire in 1835. Many country mills replaced their older wooden machinery completely or in part with iron components in the course of the 19th century. In tandem with improvements in waterwheel and windmill sail technology came the development of steam power. The first steam-powered corn mill was that built by Young and Company near the centre of Bristol in about 1779. |

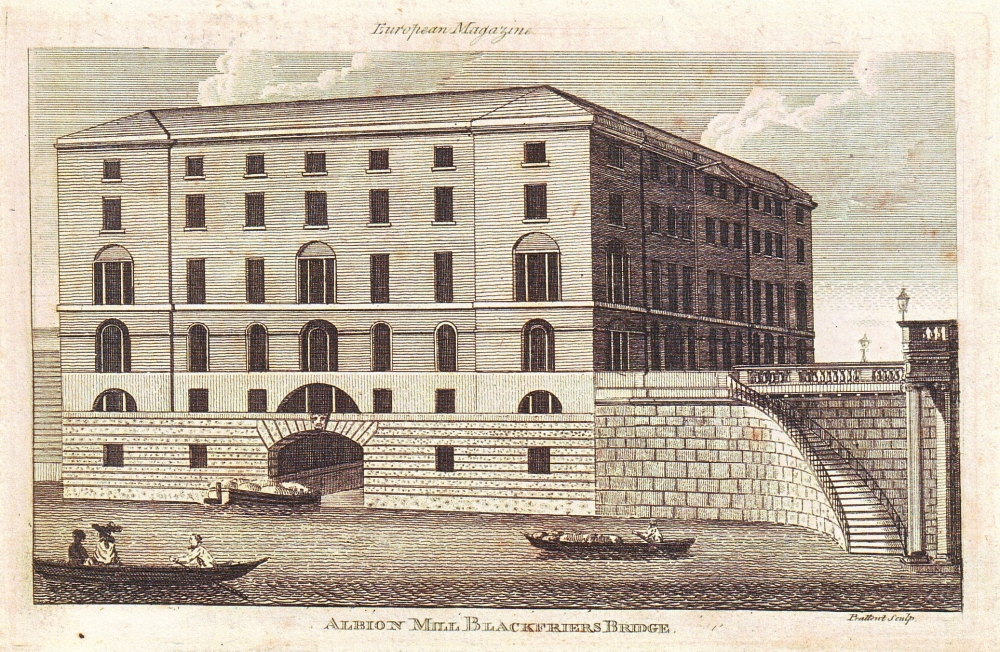

| Probably the world’s first flour factory, however, was Albion Mill built by the Thames at Blackfriars Bridge in London in 1780. The machinery, designed by John Rennie, comprised two steam engines driving 20 pairs of millstones through cast-iron gearing. Although a comparatively short-lived venture ‒ it was burnt to the ground in 1791 ‒ Albion Mill marked the start of the shift in the structure and location of the milling industry towards large mills at ports and urban centres on navigable waterways, and in doing so signalled the beginning of the demise of the small country corn mill. |